Kurla (East)’s Qureshi Nagar is defined by its assortment of big and small slaughterhouses. The neighbourhood gains its name – Kasaiwada or a settlement of butchers – from the many abattoirs.

In the past few years, the government has passed some cow slaughter legislations which have affected the people of Kasaiwada immensely. Since the slaughter of bovines became political, many in the neighbourhood were forced to pick up other odd-jobs, mostly in the unorganised sector.

The vagaries of life have kept the people of Kasaiwada from paying much attention to their children’s education.

However, people like Shaheen Qazi are trying hard to usher in small changes. She lives with her family in a one-room house. Since she studied in Urdu medium, she believes it gave her access to limited employment opportunities. She is determined to bring about a change in her 12-year-old daughter, Sehish’s, life. Therefore, she decided to enroll her in one of the training centres run by Qureshi Nagar Women Welfare Society.

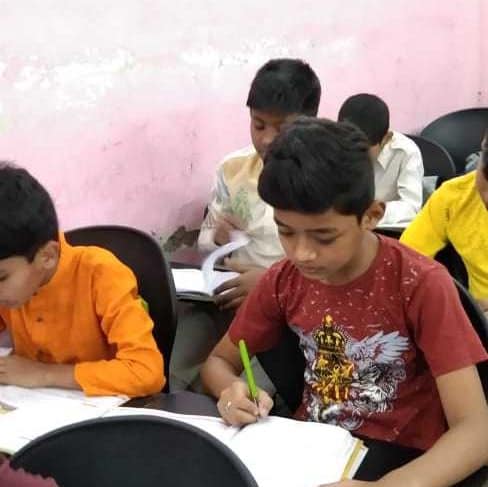

In 2013, Reshma Momin founded the non-profit organisation, QNWWS, which focuses on educating the youth. The young boys and girls of the neighbourhood loiter around without much to do, says Reshma. Her aim was to have English langauge training centres for the youth, so they have better job opportunities.

English language has long been a driver of upward social mobility. And youngesters of this neighbourhood realise that. “Many friends of mine are part of this English language learning session. It is helping me to read and understand other school subjects as well,” says Sehrish.

“Young boys who dropout of schools begin supporting their families financially in Qureshi Nagar,” says Reshma Momin, whose mother inspired her to start her NGO.

Read more: Studies must go on. Internet or no internet.

Education for social mobility

Despite being enrolled in a municipality school, 11-year-old Nawaz Sayyad Sattar used to spend all his time playing in the lanes of Qureshi Nagar, amid heaps of garbage. “As parents, it was next to impossible to manage him and I have other children too,” says his mother, Shaqila, who works as a vegetable vendor and confesses that earning a decent wage takes priority over all else for her. Her earnings feed the family and pay for essentials like water and electricity.

The other concern is that most of the houses in Kasaiwada do not have the required documents and are often vulnerable to harassment from the authorities. “Teachers in the class started with all basics of English language grammar,” says Nawaz, who felt happy to be hand-held.

Shakila is relieved that her son doesn’t loiter in the streets anymore. Moreover, he has begun to speak good English too.

Nawaz inspired other kids in the neighbourhood to attend these training centres such as Hussain Shaikh and his siblings, 10-year-old Ibrahim and 4-year-old Albira. Their mother Sajia says that she began sending her three children to the training centres after she was impressed by how Nawaz had changed. “The children either go outside to loiter or remain addicted to the mobile screen,” she says.

Sajia who was born in Kasaiwada, says the neighbourhood has not changed much in the past 40 years. It has systematically been deprived of basic amenities and remains unhygienic.

“I can see Kasaiwada changing now. Maybe the growth is really very minimal but it is really very important,” says Hussain’s mother, Sajia.

Also Read:

Very impressive work…