Much before the Right to Information (RTI) Act was passed by parliament in 2005, Karnataka had a pioneering sunshine law. The Karnataka Right to Information Act, 2000 (KRIA) was passed in December 2000 and notified in 2002. “Before KRIA, the Official Secrets Act, 1923 (OSA) was in place and that was used to deny all information to citizens,” says Kathyayini Chamaraj of Citizens’ Voluntary Initiative for the City (CIVIC), Bengaluru.

At the time, Karnataka was one of few states, like Maharashtra and Rajasthan which had enacted their own laws on citizens’ right to information. KRIA was a landmark piece of legislation which enabled citizens to approach public departments and obtain information pertaining to the functioning of these departments.

“There was an obligation to give documents to citizens even before KRIA, but government departments could ignore such obligation without reason, and did,” says Ravindranath Guru, an RTI activist.

“Before KRIA, getting information was almost impossible,” says C N Kumar, another RTI activist, who has been active in the civic space since before the time of KRIA. “KRIA was a path-breaking legislation which, for the first time ever, enabled common citizens to seek information from government organisations which thought that they were beyond sharing information. Then came this new Act which says you have to give information.”

It took another three years of significant efforts from civil society and activists demanding that information from public offices should be a common right that finally led to Parliament passing the Right to Information Act (RTI Act) 2005, which came into effect on October 12th of that year.

Read more: BBMP refuses to reopen its RTI Cell despite central guidelines, govt letters, citizen petitions

The coming of KRIA

Kathyayini traces the origin of KRIA to 1996 when Aruna Roy and Nikhil Dey’s Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sanghatan (MKSS) launched a movement for the Right to Information from Beowar, Rajasthan. They were trying to access Gram Panchayat records and the OSA was used by the authorities to block all access. The movement shifted to fighting the OSA, “because in a democracy you cannot hide information from the public who are the paymasters for the governments in the first place,” says Kathyayini. Eventually, the then CM of Rajasthan accepted their demands and made the gram panchayat records public.

After this breakthrough, more states started enacting their own Right to Information legislations and Karnataka was among the first states to do so. That was how the KRIA, 2000 was born. KRIA was subsequently denotified when the national RTI Act was passed.

“There were a few lacunae in the KRIA,” says Ravindranath, “For one, they wanted activists to give a reason as to why the information was being sought. The reason to seek information should be immaterial. Second, there was only one appellate authority if the information was rejected or delayed and if this authority didn’t approve your application, that was the end of it.” There was no second appellate authority like the RTI’s Information Commissioner. With the RTI, the first appellate authority is the department head, and within BBMP, there is now a first appellate authority for each department.

With KRIA, activists found it much easier to obtain information that could nail accountability, and it marked the beginning of what came to be known as RTI activism. Activists like Ravindranath Guru, CN Kumar, Vikram Simha, Kathyayini Chamaraj, SR Venkataram, YV Ashwathanarayana, Anil Kumar and BH Veeresh came together to coordinate their efforts, help those who wanted to access information and spread more awareness of the RTI process.

This forum came to be called the “KRIA katte”.

Read more: The dos and don’ts for a successful RTI application

Katte’s next steps

KRIA Katte was started as an open forum that used to meet every fortnight in CIVIC’s office. All those interested in RTI could air their problems and the convenor would advise them. They also started doing awareness programs about RTI, says Kathyayini.

Over time KRIA Katte was registered as a Trust with Ravindranath Guru, CN Kumar, Anil Kumar, YV Ashwathanarayana, SR Venkatram and Kathyayini Chamaraj as trustees. Ravindranath was named Convenor. “The Public Affairs Committee (PAC) under Dr Samuel Paul facilitated the forming of KRIA Katte, but later CIVIC started providing support to it,” says Kathyayini.

“The trust would meet regularly to discuss issues pertaining to RTI and would also meet the State Information Commissioner every three months. We would go and air our problems with RTI and provide feedback on the process,” says Kathyayini. The activists would inform the public about these meetings, so anyone who had issues with RTI could attend and air their grievances with the Information Commissioner. The members would also organise regular RTI clinics for the public to learn more about using the act to get public information.

One of the main activities the Katte initially got involved in was Section 4 of the RTI Act, which requires Public Authorities to declare information about their functioning suo moto (See box). “The Information Commissioner agreed that the suo moto disclosures of BBMP and BDA were lacking and directed them to take the help of Kria Katte and CIVIC to improve their disclosures,” says Kathyayini.

KRIA Katte members had several dialogues with BBMP and BDA on how to improve their suo moto disclosures. But Kathyayini says they eventually scuttled it, saying that they’ll go through an open tender process – “The Information Commissioner directed them to seek an exemption using an existing exemption clause for certain kinds of work. But the officials used this opportunity to scuttle the work.”

What Section 4 states

Section 4 of the RTI Act requires Public Authorities to declare suo-moto (on their own), information about their organisation, functions and duties.

- Sec 4.1.a requires that public authorities maintain an indexed list of their files so that people can access them easily without having to apply for RTI.

- Sec 4.1.b provides a list of items that each public authority needs to publish on its website. This list includes, among others, items such as the particulars of the organisation, its functions and duties, the powers of its officers and employees, and the categories of documents that are held by it.

- Sec 4.2 makes the public authority responsible to make all the information in 4.1.a and 4.1.b public, updated regularly and accessible not only through the internet, to ensure that the public have a minimum need to resort to RTI to obtain any information.

One of the lasting legacies of the Katte was helping draft the national RTI act of 2005, with experience from using the KRIA act. “After 2002, the movement for a national RTI act had gathered force and people from MKSS used to come to Bangalore and circulate drafts of the bill and hold public consultations,” adds Kathyayini. “By then KRIA Katte was active and was part of the process of drafting the bill”.

Read more: How to get a good road in your neighbourhood

Two decades of Right to Information

It has been 20 years since the KRIA was enacted, followed by the RTI, 2005. The experience over time has been frustrating and bitter for those on the frontlines.

“They (the authorities) do give the information, but they are confident you cannot do anything with it,” says Ravindranath. “With 17 years of experience, the officers are confident that they can beat the system. Recently there was a report that there were 30,000 RTI requests pending with the Information Commission. I applied to the Slum Clearance Board in 2017, but the hearing with the appellate authority came in April 2022. If the information has come after five years it is no longer important.” The law stipulates the maximum time for a response as 90 days. Ravindranath feels, “over time the law and its provisions have been diluted.”

CN Kumar agrees. “Officials don’t feel like they have to give you information. They know that the appeals process which used to take days is now taking years. Information needs to be timely, otherwise, it loses its value.”

Kathyayini traces the rot in the system to the way Information Commissioners are being appointed. “The appointment of State Information Commissioners is becoming political,” says Kathyayini. “This needs to stop and an open process needs to be brought in. Even the Act says that you should look at other sectors, beyond retired bureaucrats. That is not happening”.

“We are losing faith in the whole setup. From CIVIC, we are no longer filing RTIs or following up on them, and are choosing to focus on Section 4 of the RTI Act. At least whatever they should be declaring suo-moto, we are trying to ensure that that is proper”.

Read more: Resident pushes BBMP to improve shoddy process for road laying

Whither KRIA Katte

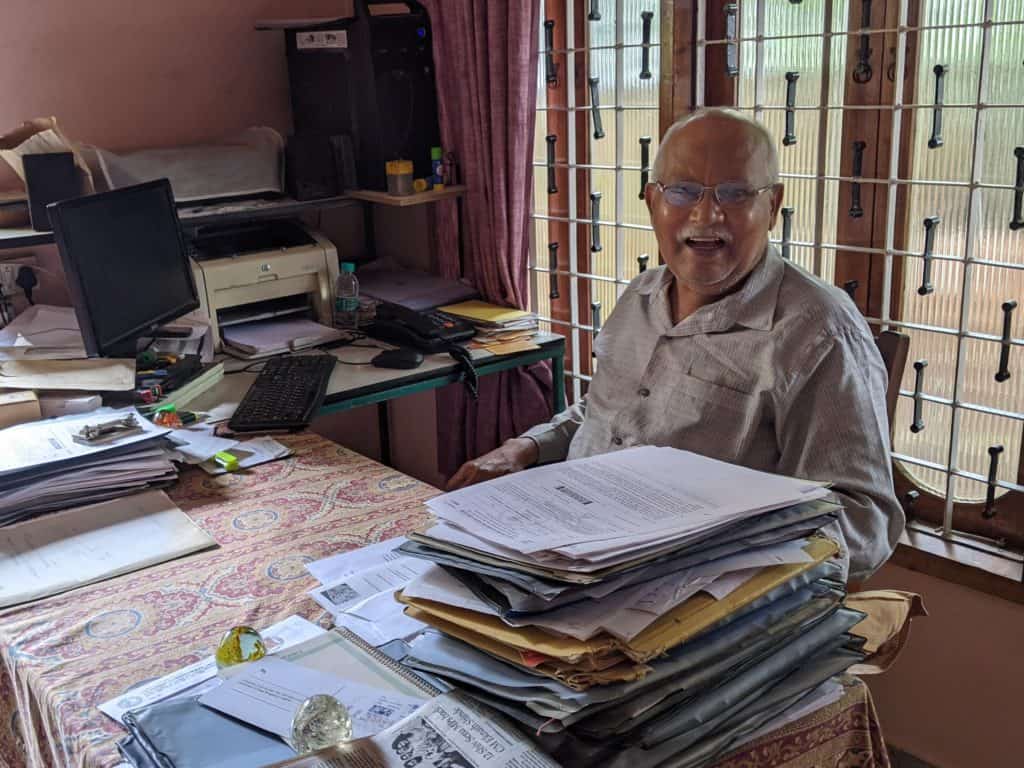

Ravindranath points out members of the Katte have aged, “One of the trustees is 92, another is 90. I am 79 and my family has been asking me to stop for health reasons. Younger people are being asked to take over, but younger RTI activists have their own fights with the system which are keeping them busy.”

Kathyayini is more optimistic. “Covid stopped our activities, but now we should be able to resume as before. We also need to find younger members to replace the older trustees, but we should continue. We will not let it go.”

The Right to Information Act, 2005, was considered a landmark legislation that was expected to open up closed government spaces to more public scrutiny. Over the decades, common citizens have used the act to unearth discrepancies in the functioning of public bodies and nail accountability.

The government has also tried to fight back in different ways. The law has been diluted, the appeals process has been broken leading to a piling up of RTI requests and RTI cells have been closed down. While the generation of activists that fought for, helped shape and ushered in the RTI is ageing, the next generation of activists is finding themselves fighting the same battles right from scratch – for a credible, dependable ‘Right to Information’ system in the country.

Namaste! I wish to submit my RTI to BBMP who are not registering brand new flats in North Bangalore since 01 August 2025. Due to non registering of flats we have to pay 1% additional stamp duty also.

I am a Senior Citizen based out of Gurugram and have no idea of RTI filing and shall appreciate your assistance for a noble cause

Any fees to be payable please be upfront so that we do not have any surprises later on