Chief Minister Siddaramaiah has written to the Union Ministry of Urban Development about having only Kannada and English signages in Namma Metro, based on the state’s two language policy.

.@CMofKarnataka has written a letter to Union Minister @nstomar saying BMRCL would be asked to redesign Name Boards etc without Hindi Script pic.twitter.com/HSD5ujtQ8k

— GoK Updates (@GOKUpdates) July 28, 2017

So after a sustained #nammametrohindibeda campaign online that lasted over a month, it looks like Hindi signages will have to go. BMRCL has asked the state government’s permission to change the boards.

The Kannada Development Authority (KDA) wrested with the responsibility of protecting and developing Kannada language asked Bengaluru Metro Rail Corporation Limited (BMRCL) to follow two-language policy and change the language in Metro signboards to Kannada and English.

Outrage started on Twitter

On June 17th, the then-President Pranab Mukherjee inaugurated the southern line of the Metro, and four days later, the news was forgotten with the new controversy.

By June 21st, the #NammaMetroHindiBeda campaign was initiated online to protest against the Hindi signboards and public announcements at the Namma Metro stations. And many Kannada activists came out on Twitter, in strong support for removing Hindi signs.

There is no need for Kannadigas to convince external parties why there shouldn’t be Hindi. It’s the other way round. #NammaMetroHindiBeda

Earlier it was East India Company now it is North India Company. English colony to Hindi colony that’s all happened #NammaMetroHindiBeda

— Kanaada Metikurke (@Metikurke) July 4, 2017

Finally..BJP leaders in karnataka should stand by Karnataka CM. They are all first kannadigas and then their partymen #nammametrohindibeda

— Amarnath S (@Amara_Bengaluru) July 6, 2017

The enthusiastic response to the campaign and the following media attention inspired neighbouring Maharashtra, which launched its own #AapaliMetroHindiNako to a fervent response.

Media covered this at great length and well-known personalities like Prakash Belawadi threw their weight behind it. With the topic trending on media and debated at water coolers, the state government realised the need to step in.

In early July, Metro officials had played it safe by masking the Hindi signboards in metro stations in Kempegowda interchange at Majestic and Chickpet. Masking the Hindi lettering was apparently done to preempt pro-Kannada organisations from possibly taking the matter into their own hands, though a few activists belonging to pro-Kannada organisations tried to blacken the Metro signages and got arrested by the police. Meanwhile BMRC increased security in some more stations, including MG Road, with the help of KSRP platoons.

Chief Minister Siddaramaiah and his Congress party said that Hindi should be removed from Namma Metro station boards; and that only Kannada and English should be used. But Union minister of statistics and programme implementation D V Sadananda Gowda rooted for a three-language policy.

What’s new in the language debate?

Nothing.

The anti-Hindi imposition sentiments are not new, and have been flaring up on and off from the 1960s, when Hindi was supposed to have replaced English as the official language. In Tamilnadu, Hindi was dropped officially from curriculum and official language list by the state government in 1968. But in Karnataka, the opposition was not strong enough, and Hindi was taught as a language in schools.

As recently as 2008, there was criticism for the Parliamentary sub committee that had a display board exhorting,“Use Kannada at home, use Rajbhasha (Hindi) in office.” The team was reviewing the implementation of Hindi language in Mysore.

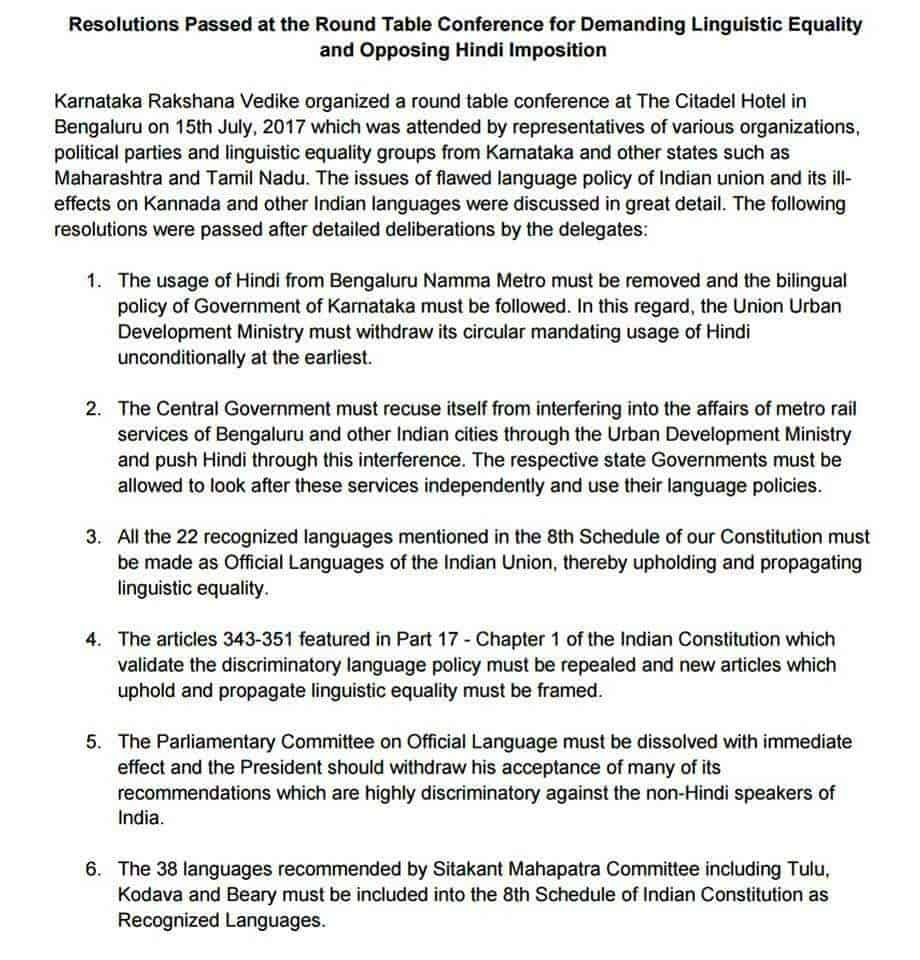

Karnataka Rakshana Vedike met on July 15th, 2017, to discuss the issue, and passed a resolution asking that Hindi be removed from Metro signages, Parliamentary Committee on official languages be scrapped, all 22 scheduled languages be given official status and smaller 38 languages identified by Sitakanth Committee be included as recognised languages. The full list of resolution is here:

Controversial official language policy at the heart of the debate

The central government is committed to propagation of Hindi – with a dedicated Committee of Parliament on Official Language. They focus on how Hindi usage can be increased in government correspondences by providing training, creating posts that require knowledge of Hindi, publishing Hindi manuals etc.

The Namma Metro controversy is only a small example of the state’s conflict with the national Official Languages Policy. Indeed, as Metro officials explained, it is the centre’s Ministry of Urban Development that directed BMRCL to follow the three language formula. In December 2016, a Parliamentary Committee had visited Namma Metro to check the implementation of the three-language formula.

What’s in a language?

Some may ask what the big deal is. When Kannada is present anyways, why oppose Hindi? Bengaluru has always been very accepting of Hindi. A significant number of locals understand and speak Hindi. But with recent influx of a large number of migrants, with a major chunk from the north, it has become common to see people who don’t know Kannada at all, in public spaces, whether in Metro trains or at the markets and malls.

Because, in Bengaluru people can survive without knowing the language, many newcomers did not see a reason to learn Kannada. This in turn has resulted in a feeling of being taken for granted and local culture being disrespected, among local Kannadigas. Many Kannada activists compare the no-Hindi policy in Tamilnadu to point out this. This has led to a simmering irritation to what is seen as Hindi imposition. This has also been exploited by political interests.

How many Kannadigas in the city?

Historically Bengaluru has been of a cosmopolitan nature, a home to many other languages other than Kannada. Tigalas who started Karaga here, Tamil-speaking Iyers and Iyengars who settled in the city generations ago, Reddy farmers who have owned large tracts of lands for a long time and now dominate the real estate in South Bengaluru, or businessmen in Chikpet coming from Gujarat, Konkanis, Marathis and Bengalis who migrated to the city and settled here – the city has them all.

Thus, though Kannada is the official language, Bengaluru has always had a large Telugu, Tamil, Malayalam, Urdu and Hindi-speaking population, and myriad other languages. Haven’t you seen those Mangalore Stores in all parts of the city, where you are greeted in Tulu? All these other languages command as much respect as Hindi deserves.

Imposition doesn’t work, for any language

The extent of anti-Hindi agitations took a new turn when people start demanding the removal of Hindi-speaking migrant workers employed in housekeeping and security jobs in Metro stations. The latest news is that Kannada Development Authority Chairman, SG Siddaramaiah, wrote to the chief secretary of the Government of Karnataka, questioning the employment of seven engineers of non-Kannada engineers. He said this was in violation of Sarojini Mahishi report that suggested 100% reservation for Kannadigas in government employment.

However, the real problem lies in a traditionally cosmopolitan city losing its character amid the agitations and protests. It should be noted that Bengaluru’s cosmopolitan nature was one of the contributors to the city becoming an IT hub in India, while there were other metros in the country vying for attention.

It is high time, all the governments realise imposition never works, whether it is Hindi or Kannada. Soft power has always worked better. For instance, Bollywood has gotten more people to learn Hindi than any Hindi Prachar Sabha.

What’s more, being an IT city with a society of increasing influx, we should be able to use technology and innovative design to remove language barriers. Signboards in the official languages of Kannada and English can be supplemented with information kiosks in myriad other languages that help visitors.

Even more critically, we need to make our signboards and public spaces more inclusive for our own people. Braille and audio signages, anybody?

Shree DN and Rehmat Merchant also contributed to this article.

Hi, If you happen to visit any hospital or train station in Mangalore or Bangalore, the most common language is Malyalam. Most of the staff are from Kerala. Infact they will start the conversation with you in Malyalam. I had to many times tell them, I dont understand Malayalam and they then make a big face, as if we are supposed to learn it by default.

Similalarly if you go to any Interview for a Job in IT capital Bangalore, most HR people are from North India Speaking Hindi. Sometimes you will not understand certain Hindi words as they speak very fast. They give preference to Hindi speaking candidates from North India. Highly qualified and experienced people from Karnataka are without jobs due to overflow and large scale mass migration of north indian people and people from other states for better jobs and facilities.

The first step government should take is that all HR and clerical jobs should be reserved for first local people and local talent. There is no shortage of local talent. Only it has been taken over by north indians and now local people find hard to get jobs.

Even the low end jobs like drivers, security guard and cleaner jobs are gone. Local people have no jobs. Please some one help local people of karanataka. Jai Karnataka.

Thanks.

Your comment that Kannada should not be imposed like hindi, is not correct… In karnataka, the state language has every right to be given preferential treatment

Disagree with this —> “Bollywood has gotten more people to learn Hindi than any Hindi Prachar Sabha”

Bollywood rules Indian movie market with senseless masala movies because Hindi was imposed on all of India, and for no additional effort, Hindi movie industry had access to a huge market that was created at tax payer’s expense.

Similarly, if Kannada had been compulsory all over India, Kannada movies would have been in a similar cess pool of senseless movies, because they had access to huge markets.

With the current trend in the Kannada movie industry where a new breed of movie makers are risking it all by going for quality, originality and locally relatable content, the Hindi movie industry would be decimated in Karnataka, if no Hindi is taught in schools. But such is the grasp of the Hindi language in the country with 60+ years of imposition that it is truly difficult to realize it’s side effects and unjust market dynamics resulting from it.

Namaskara

All languages including Hindi and Kannada should be treated equally as they are all national languages of India.Assimilation of smaller languages suppresses smaller cultures and identity.

School can be a great start to learning multiple languages.Diversity is beautiful and should be embraced by all.

Me > my family > my community > my region > my state > my country > empathy. We are a diverse set of people and it we do not agree to have things in common, I see no hope for us. Politicization of issues such as this fragments us human masses into sparring factions and takes the focus away from key issues such as health, governance and well being.