Indian cities have long suffered the absence of coherent and consistent policy-making on urbanisation. As a result, they are plagued by governance deficits, inadequate infrastructure, poor land management, unequal access to clean drinking water, repeated bouts of flooding, severe densification of some areas and poor quality of air and public spaces.

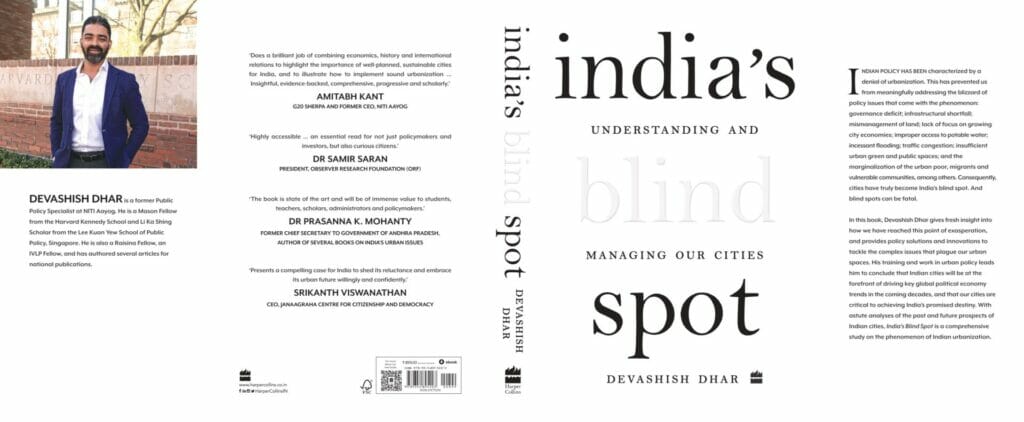

For Devashish Dhar, a former public policy specialist at NITI Aayog, these are evidence of Indian cities being a blind spot in planning and policy. In India’s Blind Spot: Understanding and Managing Our Cities (Harper Collins India, 2023), Dhar examines historical processes that led to haphazard development of Indian cities.

He argues that cities are central to achieving better overall economic growth, and that policy solutions and innovations can address concerns of inequality and marginalisation of the poor in the big cities.

Formerly a Mason Fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School and Li Ka Shing Scholar at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, Singapore, Dhar is also a Raisina Fellow and an IVLP Fellow. In this interview, he discusses the peculiar characteristics of Indian urbanisation and its challenges.

You say that India must promote ‘healthy’ urbanisation. What are the tools of the state or government that we must strengthen for a healthy urbanisation process to be born and thrive?

For quite some time, cities have been seen primarily as spatial entities, but I would rather think of them as economic-spatial entities. Making the economics of a city work is really important, and that is the overarching principle.

Read more: NITI Aayog study focuses on economic potential of Tier 2 and 3 cities

Two forces are in action in a city: agglomeration, which we want to leverage, and congestion. These forces fight against one another. It is important to tackle congestion, but I am optimistic about it, since all major cities in the world have had this problem but overcame it. London, New York, Tokyo, they all had congestion and it usually gets a lot worse before it becomes better.

The other thing is urban infrastructure, which can provide a better quality of life, including 24/7 water supply, waste disposal, sewerage, etc.

I think the third is safety, which I would place among the top five things cities need, because our cities are not inclusive right now. People are well aware of the low rates of female participation in the labour force, for example. Safety also includes law and order, road safety, child safety, the latter being an aspect on which there is very little work done.

Next, urban centres need public health facilities. These are the things we have to ensure to achieve and sustain a well-functioning city.

But the other really important factor is to make cities function. We have been dogmatically pursuing state-level growth, national growth, but we’re not focusing on city-level growth. I mention in the book a bunch of ideas focused around clusters to make people aware that city economies can steer the national economy, and we need to make those city economies function. To support that, we have our services clusters, textile clusters, auto clusters, etc, but there is also a suburbanisation of industries underway. Instead of being in the cities, they’re moving out. And that is a problem for us because then we’re not leveraging the agglomeration benefits.

Planning is central too, for our city plans have been stringent, static and focused on single-use neighbourhoods for really long. This needs to change too.

This is what healthy urbanisation looks like. The city belongs to all. It gives people a better way of living.

Your book lays a lot of emphasis on economic growth for cities, and you’ve cited evidence to show that urban hubs can be a driver of national growth, but is the focus on growth misplaced when inequality is as high as it is in India? Growth tends to hide deeper structural problems.

In the second chapter, I’ve discussed how emancipation from caste-based and gender-based issues will happen in cities, where what you bring to the workforce matters more than background. This is something that is foundational for me.

In the third chapter where I discuss the economy of a city, it is clear that if a city is not safe, if it’s not inclusive, if people do not have access to housing, to urban infrastructure, to safe transport, to law and order, then it’s not working.

I start this chapter with migrants, informal workers, who have a large role to play in building efficient cities. I have had discussions with senior policymakers on how we treat migrants in our cities, on how the rich and prosperous look at migrants as something that needs to be hidden. In fact, if migrants are coming to your city, it means you can be happy, we need to make space for them, just as we need to make space for better female workforce participation.

Read more: Migrant workers deal with unhygienic living conditions, poor nutrition

As a student of economics, I think that after a certain per capita income, inequality will decline. It will happen when we are able to distribute more resources towards social outcomes including better urban healthcare, urban educational facilities, etc. These find a strong mention in my book.

We saw during the pandemic that migrant workers were forced to walk back or hitch rides home, not having any social security or cushion whatsoever. Jobs in the cities offer them low dignity. How do we get around that?

I want to unpack a couple of things: When I refer to migrants here, I’m talking largely about the informal labourers. Because many of the rest of us are also migrants in cities. I am a migrant to Delhi, having come from Lucknow. I always say we must look at the life-cycle of generations of migrants. Some of us were able to do better because one of our forefathers came from a village to a town and managed to give better educational opportunities to their subsequent generation.

Poor migrants leaving agriculture to move to cities tend to join the informal labour force as unskilled labourers, or the semi-skilled or unskilled self-employed workforce. This is something that is unavoidable, that churn has to happen. It happens in every country. You know, even people who moved from Europe to the US had to live on low wages as unskilled workers. Someone in the lineage has to do that, before later generations do better.

The lack of dignity and other social welfare benefits is something that is incumbent upon the state and also we have to give a lot more to the informal workers we are engaging, whether the man we’re buying puchkas from, or the man who comes to pick up your trash or drop the newspaper off.

I think this also has a cultural context, where we tend to look at people through their profession.

On social welfare, I strongly agree with you. That is why there are extensive recommendations in the book regarding truly affordable rental housing, education, assistance even for things like creating a bank account.

I would say that COVID has ingrained in our national consciousness just how migrants were helpless. After all, it was the largest movement of people since Independence and Partition.

Some states, clusters and cities have certainly been more accepting of migrants than they have in the past. Mumbai for one is very accepting of migrants, as is Gujarat where there are migrants in Ahmedabad, Vadodara and Surat. Surat was the first city to have affordable rental housing for migrants. In Kerala there are some clusters doing really well. Bangalore now belongs to India.

So overall, I think culturally we are accepting of migrants, but in terms of dignity, certainly they have a great deal of hardship and more needs to be done to improve their lives in the urban clusters.

How did you decide to write this book, and what are the cities in India that have caught your imagination, particularly Tier 2 towns?

At the NITI Aayog, I was to be part of a team drafting national policy documents. It so happened that I was late for a meeting by a couple of minutes and by then the sectors I’d planned to pitch for were picked up by others.

So Arvind Panagariya, then vice-chairman of the NITI Aayog, asked me what sector I’d like to work on. Eventually, I thought, what are the sectors that are gonna matter for India, and those are urbanisation, energy, water resources.

That’s how I picked urbanisation. But when I looked for a book to do some reading on the subject, I didn’t find one that covered the entire subject.

As I was part of the VC (vice-chairman’s) team, we had incredible exposure, we listened to global experts from every sector, we organised countless meetings and consultations, we could learn from CEOs and innovators, filmmakers, creators. That is how the book emerged. If it was not for NITI Aayog, this book wouldn’t have been possible.

And the book is for everyone who would like to understand how our cities fared in history, how they are transitioning now, what global geopolitical factors have come out of Indian cities; there are solutions that not everyone may agree with but I wanted to put something out there to start a conversation.

I wouldn’t like to pick one city that has caught my imagination, but some cities poised at very interesting junctures are Agra, Jaunpur; some industrial towns in eastern India such as Jamshedpur have evolved private solutions to public problems.

In the south, Tiruppur, Tiruchirapalli are doing well. Tiruppur of course is very textile-focused, but Hubli-Dharwad is poised to grow further. Tourism will grow Amritsar further, Thiruvananthapuram has a lot of potential for services. I don’t know why we’re not leveraging Rameswaram – I am all for temple towns. Why not Ajmer, another example that could do very well? These are all cities that have something in the making, not just those already doing very well.

The path of urban planning has not been taken very well by most of our cities. What would be their biggest challenges going forward?

The informal sector simply doesn’t show up in planning. City and state governments choose not to recognise this huge influx of informal workers, because if they do so they would have to provide some services.

The second challenge is the lack of mixed-use areas. And the third is to look at cities like Mumbai as part of a metropolitan region, and plan for the region. I know that the agency for the metropolitan region exists, but you don’t still have a unified transportation system, or a single payment card, or last-mile connectivity.

The next is rethinking land, such as the plans for the eastern waterfront in Mumbai. We think of land in very static terms. We have to recycle land because we only have so much of it–an apartment today could be a museum tomorrow. We have to think liberally in terms of floor area ratio—Indian cities have a very, very low FSI as compared to their global counterparts.

For the longest time planning was an essential tool to direct urbanisation. We did not do a great job of it. How can we engage the private sector? How many urban planners do we have? What kind of municipal finance do we have? These things play into the larger master-planning exercises, for we may have the grandest of plans, but if you do not have municipal finance and municipal staff to monitor and regulate, plans tend to remain only an exercise on paper.