Those familiar with Hyderabad would be aware that it was once known as the City of Lakes. Today, if we do an online map search for the lakes of Hyderabad, we still see numerous blue spots but the city that boasted of about 7000 lakes and tanks has seen the numbers dwindle steadily over the years.

Why is Hyderabad losing lakes?

Like many urban cities, Hyderabad been facing the problem of fast vanishing lakes. This should not be surprising, given that many of them were small, and lost to the government’s decision to convert water bodies that were of less than 10 hectares to residential or commercial sites. On record, there are 169 water bodies** in Hyderabad (all supposed to be of over 10 hectares). Of these, 62 are fully owned by the government, 25 are privately owned and 82 are under joint government-private ownership.

Even these few lakes and tanks are under threat with the Telangana High Court, in 2021, having told the government to save them from builders and encroachers.

Our nearby “Temple Lake”

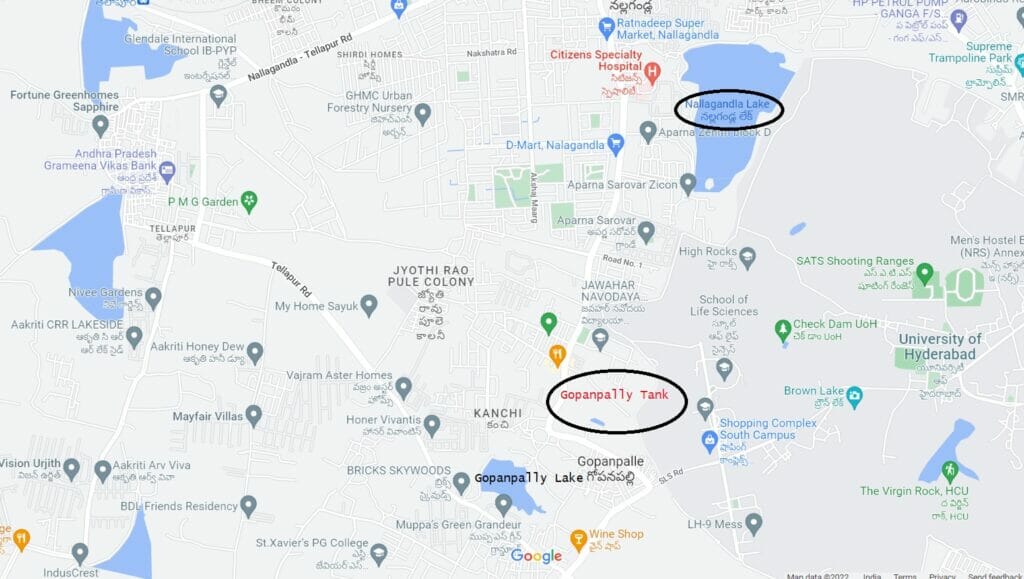

My interest in lakes was sparked by the frequent sight of what once looked to be a thriving lake, close to where I live. It is officially called Gopanpally Tank, and commonly referred to by locals as Devi Kunta Lake or Lord’s Tank. The lake is located right in front of the ancient Sri Ranganathaswamy Temple and is said to have been a part of the temple property right from the times of Krishnadevaraya. People also call it Gopanpally Lake but I discovered that there is a much bigger lake by this name in the vicinity, that is being maintained by a builder.

Read more: Rajokri Lake: From wasteland into model lake in just a year

Currently the lake is in a sorry state with garbage and debris being dumped all around, contaminating whatever little water it has, and putting the residents of this relatively poor neighbourhood at risk. I cannot but compare the lake to another big lake in the vicinity – the Nallagandla Lake that is abutted by posh high rises. A few years ago, this lake was restored to its old glory and is now a great place to relax and see birds in their natural habitat.

The priest of the Sri Ranganathaswamy Temple says that a couple of years ago, the government had promised to restore the tank, clean it, build a walkway around it and make it accessible to the public. According to him, some cleaning operations do happen once in a while, but nothing substantial has been done, other than the construction of a watchtower. There are encroachments and the inflow channels are completely blocked. The priest says that the water that we see now is only because of the heavy rains we had this year.

Restoration is the need of the hour

We’ve seen reports about how India is going to face a severe water crisis in the years to come, and can only think of the lakes that in the vicinity that could save us. Though the water may not be potable, a healthy lake raises the groundwater table. This would make water from wells and borewells more accessible. If Nallagandla Lake could be restored, there is no reason why the Gopanpally Tank should be seemingly slowly dying.

Some basic deweeding and desilting on the lake bed is required, along with clearing the blockages to the inlets and outlets. The temple priest is hopeful that the government will take action in the next six months. So do I and the residents around the lake.

** Errata: The number of water bodies had been mistakenly written as 162, instead of 169, in the first published version. The error is regretted.

Also read:

- Keeping Hussain Sagar Lake free of floating waste

- Study on cascading lakes in Hebbal explains why so many of them have dried up

- MOUs or no MOUs, citizen groups continue the fight to save Bengaluru’s lakes

most of the biggest encroachers of the lakes seem to have become part of the governments over the decades thus speeding up the lakes vanishing

This is a fantastic piece of reporting and research. We should try to preserve our environment. As the world is finding out, seeding concrete jungles has brought us to the brink. The government should act to restore these water bodies.

Water Bodies are needed to be preserved for the Future. Development cannot be playing with Nature. Climatic Changes are not there to be ignored any longer.