The business and busy-ness of surviving in Mumbai leaves little time for city-based trivia. However, learning about how the city’s streets and neighbourhoods are named isn’t solely about familiarization. By understanding our past, we can attempt to make better sense of our present.

With the help of two rare and rather forgotten books, I did a cursory study of names of different spaces in Bombay. One book looks at the meanings of local names ordained to nooks and corners in Bombay. The other conducts a formal investigation into the official story of how this archipelago came to be.

My short onomasticical study threw up an assortment of interesting tidbits.

“In Bombay there are no finger posts to history,” writes Samuel Townsend Sheppard in a book named Bombay Place Names and Street Names. Published in 1917, the book is an archival process that documented what etymologically makes up Bombay. Not much is known about Samuel Sheppard. He does have another noteworthy book to his name, Byculla Club, 1833-1916: A History, which records how the suburban club for Bombay’s British residents was built and its eventual disintegration.

Sheppard tucks a litany of anecdotal and sourced bytes in Bombay Place Names and Street Names. Some of the most memorable are those that we can see around us till today; landmarks that reflect time in language. He walked the city streets with intention, with the knowledge that even a moniker scribbled somewhere can unfurl hidden pasts.

Early traders and merchants come up aplenty. The infamous Parsi neighbourhood of Batliwala Mohalla is dedicated in parlance to merchant and philanthropist Jamshed Jeejabhoy’s uncle, Framjee Batliwala whom he lived with after his parents’ passing.

Near the Mohalla in Crawford Market runs the popular Abdul Rehman Street which, according to Sheppard’s sources, was the mark of a Konkani Muslim man who owned vast swathes of land there in the 1700s.

The secret librarian

While Arthur Crawford, the first Municipal Commissioner of the Bombay Presidency, after whom Crawford Market is named, is prolific, little is known about his ‘Managing Clerk’ Bhai Jivan.

The book speaks of little known landmarks such as a dead-end road called Bhai Jivanji Lane which extends from Girgaum Road. Bhai Jivan was “a great book collector and had a valuable library which was dispersed after his death in 1906”.

Seeing that the Marathi Grantha Sanghralay was erected on the lane in 1898, we can presume that Jivanji, who “possessed several properties in Bombay”, would have had some semblance of a relationship with the public library.

Arabic connection to Bambai

Arab Lane can be found about two kilometres away from Bhai Jivanji Lane. A turn away from Grant Road’s popular Kabootar Khaana, Arab Lane was demarcated for the Arab pearl merchants living there at the time.

Fofalwadi on Bhuleshwar road also lingers with the residue of Arabic language. Fufal is the Arabic word for betel-nut, of which several areca catechu trees stand in the ward even today. This isn’t the only tree-inspired nomenclature in the slowly de-greening city. Umarkhadi, earlier a natural border between Mazgaon and Dongri, is a literal translation of ‘fig tree creek’ with fig trees having dotted the stream while Sheppard was alive.

What these signifiers make clear is that migration, both international and internal, has historically been critical to the landscape of Bombay.

Early migrations into Bombay

Towards the south of the island city is Ladiwady, a trail called so because of a Gujarati migrant caste group that self-identified with ‘Latdesh’ (an earlier name for Gujarat).

Even further south, Agripada utilizes the -pada suffix from “Kanarese” or Kannada which means hamlet. Sheppard writes that it takes ‘Agri’ from the caste of cultivators called Agris. He goes on to distinguish between three sub-divisions of Agris, rice cultivators (Bhat), salt manufacturers (Mitha), vegetable growers (Bhaji-pala). He also claims that “according to the most widely-known Marathi accounts”, the first migration to Bombay happened with seven connected families of Agris in 1294.

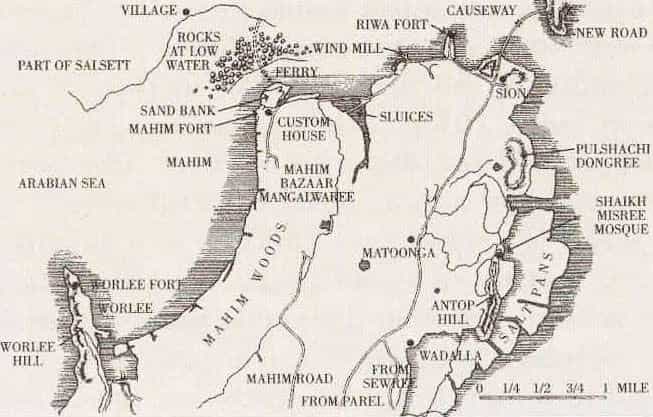

The seven islands grew rapidly in population, financial muscle, and diversity after the 13th century. Dynamic trading communities have left touchstones of their legacies, visible in parts even today. The most prominent impact on Bombay’s geography was that of the East India Company and the consequent reign of the British.

Also read: What’s common between Gateway of India, Kala Ghoda and Blue Synagogue?

Bombay – post-independence

Bombay: Story of the Island was published in 1949 by A. D. Pusalker and V. G. Dighe who were eminent historians. Pusalker was a scholar of mythology and ancient writings while Dighe’s specialization was of the Maratha empire and writings in Marathi.

Their book holds the zeal of a newly independent nation attempting to craft its own epic narrative.

The text makes for an interesting compendium to Sheppard’s Bombay Place Names and Street Names. Agripada, for instance, is mentioned under the reign of the Shilahara dynasty which ruled over parts of the Western coast prior to the 1300s. This could corroborate with Maharashtrian accounts of Agri ‘immigration’.

Pusalker and Dighe provide a comprehensive account of the ecological make-up and political conflicts across the city beginning from the 6th century and going up to the end of the 19th century.

Planned displacement was swiftly undertaken wherein “Koli houses on Dongri Hill were removed” in 1770; two years after which “an order was issued” reserving parts of Churchgate for only Europeans thus pushing the native populace northwards.

Of Bhuleshwar with the sweeping catechu trees, they write that it only saw serious growth after “the great fire of 1803” which demolished a third of southern Bombay. Parts of its port locales altered significantly with the construction of trading docks and the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869.

The book gives a glimpse of not only the evolution of an island but also of how it studied itself. Their information on Koli communities show that they are usually referred to as ‘original’ inhabitants because they “formed the most numerous class” on all seven islands. Several linguistic remnants such as Worli (after ‘Varli’ or banyan alley in the Koli language) attest to that even today.

Haphazard naming

The disparate sensations produced today when travelling from one end of Bombay to another is reflected in its haphazard naming. Caste names are often explicitly or implicitly designators for roads and neighbourhoods. The Maharashtra government recently endorsed a plan for removing caste-based locality or village names. One has to wonder how this extensive project can realistically pan out considering there are names which don’t immediately register as caste-based but are.

Ripon Road passes through an area known as Madanpura after an Allahabadi Muslim man, Madan, who owned land there and was from the hand-weaver caste of Julahas according to Sheppard. Back near Girgaum Road is a short lane called Mangelwadi labeled so for the fishing caste of Mangelas who lived there before Sheppard’s time.

Memonwada Road denotes the Memon Muslim converts “from Lohana and Cutch (Kachch) Bania castes” who arrived in Bombay in the beginning of the 19th century and established themselves as tailors. Pinjari Street, an extension of Abdul Rehman Street mentioned earlier, owes its title to the bow that cotton cleaners there used to clean cotton. Gola Lane, colloquially known as Golwad, found its name in its inhabitants of Golas, a tribal community residing in Gujarat and other parts of the Presidency. As per Sheppard’s research with the Bombay Gazette, Golas were forced predominantly into “rice pounding” work.

Sheppard navigates the complex dynamics these names point to casually. Perhaps he doesn’t fully realize their depth as an ‘outsider’ looking in. However, he definitely had enough knowledge to classify certain areas, such as Kamathipura, as populated by the ‘lowest’ of castes and others, like Lady Hardinge Road, by ‘respected’ families. Property ownership became one way of rising in value and wielding enough power to have a road etched in their memory. But homes of disempowered castes continued to be identified with their caste designations as a way to ensure lack of resources and constant surveillance.

Where Bombay: Story of an Island etch broad strokes of important events, Sheppard’s Bombay Place Names and Street Names dives into its effervescent details.

Sheppard bullet points Armenian Lane which stretched from Tamarind Lane to Esplanade Road and was named after a Church built there “at the end of the eighteenth century” by residential Armenians. Pusalker and Dighe discuss the political decisions of Gerald Aungier, a British Governor, who allowed Armenian traders to settle within today’s financial capital that then led to the existence of this Lane.

Little did I know

It is fascinating to see how little Bambaiyya history I knew despite growing up in the city. I have passed Charni Road station countless times in my life without ever thinking why Charni was Charni. Sheppard’s two theories are that either the name tracks an internal migration of “inhabitants from Chedni” which is located near present day Thane to what is now Charni. It could also simply reflect the usage of the desolate area as cattle-grazing (‘charna’) tracts.

Regardless of which theory is true, reading these two books made me realize that Bombay was always a place of people. It inhales and spits out like a patchwork.

One-third of the city made way for the other two-thirds to rocket their capital and capacity. Without people, the city could have been reduced to nothing. That rings just as true today.

Pusalker and Dighe’s parting words reverberate. They write that Bombay’s “preservation now depends on the good sense of its citizens, on their readiness to dwell together in unity and the willingness of its wealthy community to render justice to the millions of peasants and artisans whose labours and toils have gone to build up Bombay’s prosperity.”

Perhaps when Sheppard wrote that there is an absence of finger-posts to history, what he also meant was there is an absence of honouring what has come before; of learning from what has been wrought before.

The misery and delight lyrically woven into the song ‘Yeh Hai Bambai Meri Jaan’ now remains an honest testament to the havoc and pleasure this island has to offer.

Also read: