Tharun*, a 10-year-old boy, was living on the streets of north Chennai with his family. They made a living by collecting recyclable waste from the nearby dump yard in Kodungaiyur. The three-member family of a father, a mother, and a son, would wait until the shops in the area shut down for the day so that they could make their beds on the pavement outside the shops. On many days, the shopkeepers would water the pavement to prevent the homeless in Chennai from sleeping in front of their shops. Hardships in such a life were aplenty for the family.

One day, during a weekly rescue mission initiated by the government along with Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs), Tharun was rescued and brought to a shelter for the homeless that is run exclusively for boys below 17 years of age.

“When we asked his parents if we can take their child where he would have a safe shelter and be provided with education, his parents asked if their child would be given three meals a day. Since the parents were unable to provide proper food to their child, they sent Tharun to the shelter while they continued to stay on the streets,” says G Rajesh, caretaker of the boys’ shelter in Kodungaiyur.

Though Tharun now has a safe place to sleep and is ensured of all his basic necessities including education, the lack of family shelters in Chennai for homeless people has led to a situation where he has to be separated from his family. Lack of family shelters is just one part of the large infrastructural, financial and systemic challenges faced by the NGOs that run the shelters for the homeless and vulnerable under the Greater Chennai Corporation (GCC).

Read more: Will the Urban Employment Scheme in Chennai end the woes of urban poor?

History of shelters for the urban homeless

According to a report titled “Shelters in Chennai” by the Information and Research Centre for the Deprived Urban Communities (IRCDUC), one of the earliest programmes for the urban homeless date back to 1992, when the Union Ministry of Urban Development, introduced ‘The Shelter and Sanitation Facilities for the Footpath Dwellers in Urban Areas’ that focused on providing shelters. This scheme was renamed ‘Night Shelter for Urban Shelter less’ in 2002 and was limited to constructing composite night shelters with toilets and baths for urban homeless people. Later it was withdrawn in 2005 due to poor utilization of funds.

In January 2010, the Supreme Court directed the Central and State Governments to provide permanent 24-hour homeless shelters in 62 cities in a phased manner. The order stressed that for every one lakh urban population, facilities for shelter and allied amenities must be provided for at least one hundred 100 persons and the shelters are to remain open 24 hours a day and 365 days a year.

The Court also directed that shelters for the homeless should have basic amenities including mattresses, bedrolls, blankets, portable drinking water, functional latrines, first aid, primary health facilities, and de-addiction as well as recreation facilities. Besides, 30% of the required shelters should be special or recovery shelters for single women, the mentally challenged, the elderly and other vulnerable groups.

Since then, the Supreme Court has been regularly reviewing the implementation of its directions for the urban homeless by all state governments. There have been state-level monitoring committees appointed to monitor the programme.

In 2013, the Shelter for Urban Homeless (SUH) Scheme was launched under the National Urban Livelihood Mission (NULM), later renamed Deendayal Antyodaya Yojana (DAY) in 2015. This scheme has acknowledged the contribution of the urban homeless to the economy of the cities and sought to provide permanent shelters equipped with essential services for them.

Shelters for the homeless in Chennai

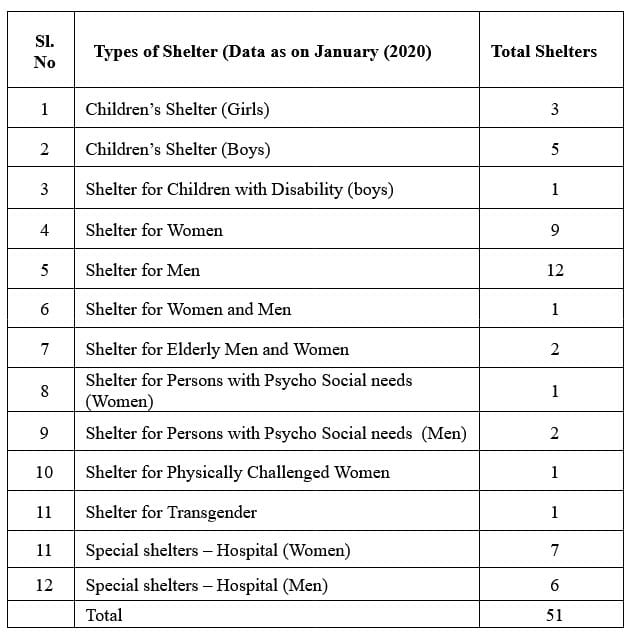

According to the IRCDUC report, Chennai has 51 functioning shelters operationalised by NGOs while another additional 33 shelters are in various stages of construction. The GCC website shows a list of 50 shelters.

While the GCC provides buildings and covers a part of expenses, the operation and maintenance of these shelters are done by NGOs which are selected by the following process

- Step 1: Advertisement in print/electronic media inviting organisations interested in managing a shelter for the homeless

- Step 2: Submission of Expression of Interest (EOI) by NGO/Organisations/Institutions addressed to the City Health Officer (CHO)

- Step 3: An assessment visit will be undertaken by a joint assessment team comprising a civil society and City level coordinator representative to assess institutional capabilities and program effectiveness.

- Step 4: SAC (Shelter Advisory Committee) to scrutinise the proposal and based on the qualification mentioned above and the assessment report of the joint assessment team, they will prepare a draft approval note

- Step 5: The draft approval notes along with the copy of the EOI and the Assessment Report will be sent to the Executive Committee for final approval

- Step 6: Signing of Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) by the Commissioner of the Corporation of Chennai and the NGO head.

Qualifying criteria for selection of NGOs:

- Minimum of 1 year of experience in working with the homeless community

- Experience in managing shelters, homes or orphanages

- Ability to demonstrate the sustainability of the programmes previously undertaken

- Experience in grants management

- Experience in working with Government agencies or projects

Challenges in running the shelter for the homeless in Chennai

We visited five GCC shelters for the homeless in Chennai. They were shelters for boys, girls, the elderly and persons with mental illness (men and women separately). Despite the range of vulnerability differing from one group to another, the cost covered by the government for the operation and maintenance of these shelters were all the same.

Also, as per NULM norms, there are only four staff members – a coordinator, a caretaker who is also in charge of cooking, security persons and a counsellor – per shelter. Their salaries are covered by the local body.

The local body performs the following functions

- Allocation of building

- Payment of staff salary – coordinator (Rs 15,000), caretaker+cook (Rs 6,000), security (Rs 6,000) and counsellor (Rs 7,000)

- Provision of Rs 27 (Rs 22 for dinner +Rs 5 for snacks) per person per day

- Provision of Rs 60 per person per month for toiletries

- Provision of Rs 120 per person per year for mattress

- Provision of Rs 13,750 per year per shelter for utensils and other such expenses

Kavya*, a coordinator of a girls’ shelter in Chennai for homeless children said that the coordinators should have a minimum qualification of a master’s degree with a specialisation in a particular subject. “However, the payment remains Rs 15,000 without any increment. Besides, the job role requires us to manage the shelter by looking into the individual needs of the persons in the shelter and the common needs like provisions in the kitchen, maintaining various records of the shelter inmates, taking part in the weekly night rescue mission and so on. In some shelters, since there will not be a separate counsellor, the coordinators will have to take up that role too,” she notes.

“While the workload is heavy, the salary remains very low. Since there is no major career growth in this field, the freshers take up the job but they eventually move out in three to six months. This becomes a drawback for the NGO as they have to keep recruiting freshers once in a while. The change in staff also affects the children at these shelters as it takes time for them to mingle with the new staff,” says Kavya.

Similarly, the role of the caretaker also includes cooking. While there is only one caretaker for all the persons in the shelter, the NGOs have to appoint a separate cook and pay for them out of pocket.

While the aforementioned cost gets covered by the GCC, Karthik*, another shelter coordinator said that it takes a sum of Rs 1 lakh to Rs 1.5 lakhs to manage a shelter that has around 30 children. “Most often, we depend on the donors and sponsors for the funds. It has become more challenging to get sponsors and donors, particularly after the pandemic,” he notes.

Virgil D Sami, Executive Director of Arunodhaya Trust, who operates a shelter for boys in Kodungaiyur, notes that the GCC has been supportive when it comes to immediately attending to civic works in the building, conducting monthly health camps and other such works in addition to releasing the funds. “However, the only issue is that the building is near the dump yard and we have requested the GCC to provide a bigger building that is in a better location,” she says.

While space constraint was one of the major issues in many shelters, the lack of vehicle facilities to take the children to schools and to bring them back safely through public transport was pointed out to be yet another challenging factor.

Rajesh had to take the eight children from the shelter in Kodungaiyur to their respective schools which are more than 3 km away by government bus. “We have a government bus at 8.10 am. If we miss that bus, then the next one comes only by 9 am. Since it is peak hour, all these buses will also be crowded. To ensure the safety of the children, we end up taking them in share autos, which costs Rs 30 per head per day,” he says.

He further added that despite many children being interested in sports, many of these shelters for boys and girls do not have a playground facility. “After school hours, they are confined within the four walls of the shelter and it affects their mental health a lot,” he adds.

Apart from the lack of sufficient physical infrastructure, since some of these shelters for children are located near dump yards and on hospital campuses, they also lack a conducive environment for the children to grow up.

Ramaiah*, a homeless sexagenarian man, who was earlier in a shelter for the homeless in Chennai, is back on the road. He had undergone an amputation procedure for which he was sent from the shelter to the government hospital. However, since there was no follow-up from the shelter, he was discharged after the procedure and was back on the streets of Chennai.

“Follow-ups become hard as there is a staff shortage in most of the shelters. Since there is only one caretaker per shelter, it becomes highly impossible to look after senior citizens who cannot look after themselves,” notes Kavya.

Policy challenges for the homeless in Chennai

Pointing out the policy challenges in addressing the homelessness issues of Chennai, Vanessa Peter, Founder of the Information and Resource Center for Deprived Urban Communities (IRCDUC), says, “As per the direction of the Supreme Court, Chennai is to have 86 shelters. However, there are only 51 operational shelters now. Besides, there is no specific programme in Chennai for the urban homeless families, who constitute the majority of the homeless population. Despite conducting inter-departmental meetings there are no linkages to housing because of the absence of policy,” she notes.

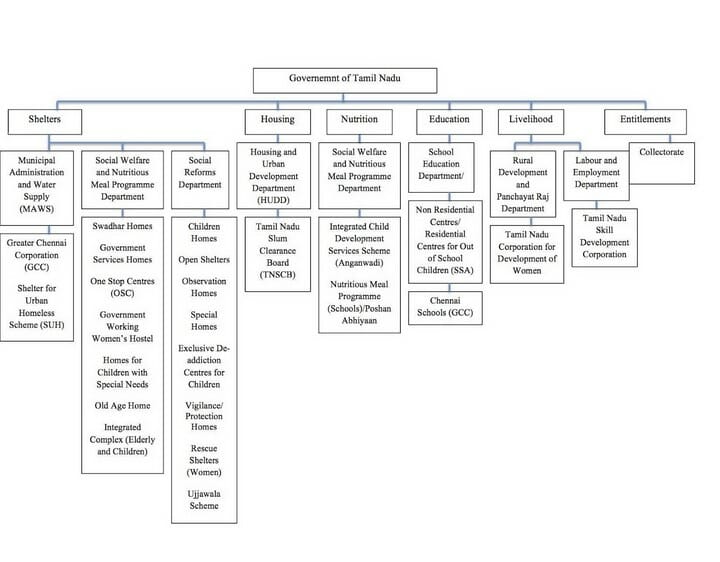

“There is also a need for a comprehensive programme for the rehabilitation of those who are into begging and persons with disability by ensuring convergence with the Commissioner of the Welfare of the Differently Abled, Tamil Nadu. This is in addition to linking the shelter programme with the existing schemes under the Social Welfare Department,” she adds.

Though there is a Shelter Advisory Committee (SAC), a monitoring committee comprising GCC officials, civil society organisations, retired government officials, experts and planners, there are no terms of reference for the members.

“Despite the fact that the Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) has outlined the roles of the SAC yet the lack of formal Terms of Reference (ToR) for the non-official members is an area of concern as their roles and responsibilities are not defined,” says Vanessa, adding that there is an emerging requirement for setting up specialised geriatric care for the elderly homeless; recovery shelters for the infirm; palliative care for the terminally ill; de-addiction facilities; and family shelters especially for the nomadic tribes.

“While the demographic and vulnerability profiles of the urban homeless are heterogeneous in nature where they face several intersectional issues, the shelters for the urban homeless are seen as the only viable solution to address the multi-dimensional vulnerabilities faced by the people,” says Vanessa.

A senior official from the GCC said that, unlike other local bodies, GCC is allotting nearly Rs 4 to 7 Lakhs annually for each shelter from its Capital Fund despite the challenges in fund allocation. A zonal official also added that steps are being taken to shift the shelter that is near the Kodungaiyur dump yard and address other infrastructural issues.

In an attempt to consolidate the views of the different civil society agencies to further strengthen the homeless people’s wishlist ahead of the Tamil Nadu Budget for 2023-24, IRCDUC conducted a stakeholders’ consultation on January 12 and suggested the following pointers

- There is an emerging need to draft a comprehensive policy on urban homeless to facilitate inter-departmental coordination and to bring the various programmes implemented by multiple departments under a policy framework to facilitate effective planning, implementation, and evaluation like the Rajasthan Homeless Upliftment and Rehabilitation Policy, 2022

- A state-specific scheme for the urban homeless with budgetary allocation needs to be evolved

- The need for institutionalising social audits for shelters and the meetings of the State Level Monitoring Committee constituted based on the order issued by the Honourable Supreme Court of India (Government Order Number: 206, dated 16 May 2018, Municipal Administration and Water Supply Department) to assess the quality of the scheme should be conducted periodically.

- All Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) to ensure that special shelters for the elderly, persons with disability, persons with mental illness, transpersons, and migrant women/men are accessible and set up in coordination with the respective nodal departments as per the DAY-NULM Guidelines.

The Minister for Municipal Administration and Water Supply in August 2021 pointed out that 53% of the total population of Tamil Nadu is currently residing in urban areas and are likely to become 60% in 2036. The urban poverty which contributes to a homeless situation in Chennai and across the state coupled with the irreversible impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the most vulnerable population calls for immediate government intervention with a comprehensive solution.

These figures also point out the need for state-level policy decisions, robust financial mechanisms to run these shelters, establishment of family shelters and integration of various government schemes to address the homelessness issues in Chennai.