While covering stories, reporters come across situations that stay with them for a long time. Like, what did a place look like? How were the people in the story dressed that day? For anyone, these are inconsequential, mundane and everyday things. But these details can speak volumes about systems, governments, and people.

Late August this year, I came across a man named Deepak Khilare who had come from Nanded to avail treatment at Mumbai’s King Edward Memorial Hospital. A month earlier, he had suffered trauma to his spine, as a result of which has was in a wheelchair. Deepak was here with his family of five.

Read more: KEM hospital experience shows what unplanned medical expenses mean for the masses

Ever since the accident, he needed support to even use the washroom. In such a condition, the Khilare family undertook a 12-hour journey of 600 km because the public healthcare infrastructure in their hometown was not enough for his treatment. The family lost their daily wage, their debts increased, and their savings had boiled down to nothing.

Deepak’s brother was speaking with me for the most as Deepak was in no condition to have a conversation. But describing the experience brought him to tears, as well Deepak’s wife.

Like the Khilare family, millions of Indians travel long distances to take the benefits of the public healthcare system in Mumbai, which should be made available to them at their door steps. State-neglect and apathy lead to the loss of lives. Deepak and his family’s story was one of the most vulnerable moments in my reporting journey, and will never leave me.

The grief of everyday life for many

I am inclined towards covering stories of public health. The health infrastructure in this country is broken and chaotic but it ensures low-cost, even free-of-cost treatments for the marginalised and the middle class.

Mumbai witnessed a measles outbreak recently, which came to light after two children living in M-east ward died in the last week of October. It was pertinent that I spoke with their parents to understand what had transpired.

The parents weren’t home when I first went to the area but other residents provided me with their contact details. What I thought would be a short call the next day lasted more than an hour.

Mehrunissa, the mother, narrated the ordeal of seeking emergency care. She told me how there needs to be a good hospital in her area so that in situations of life-and-death people don’t have to run all the way to Rajawadi Hospital in Ghatkopar.

Read more: Missed vaccines, misinformation and other gaps highlighted by Mumbai’s measles outbreak

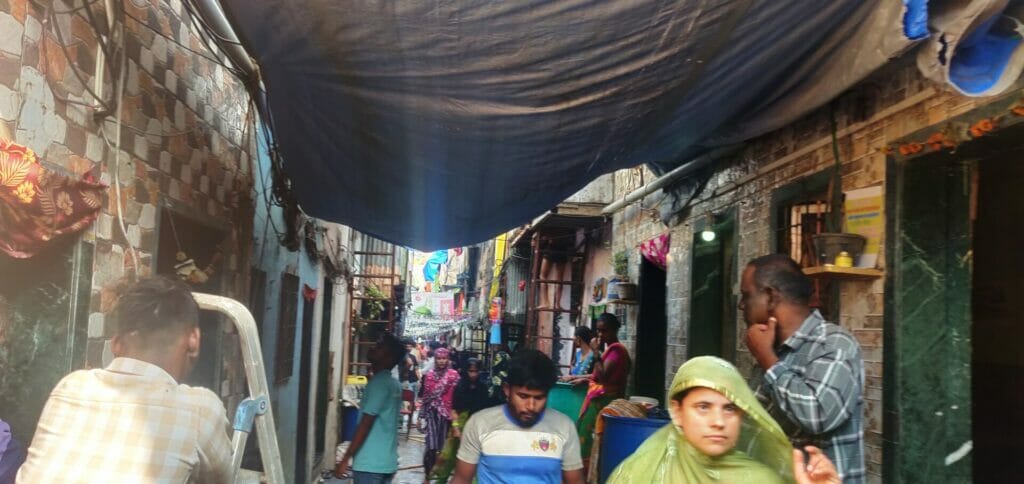

But the conversation took a turn after about 30 minutes. The mother started complaining about everyday problems in her slums, from uncertainty around electricity, to the toilet facilities, to contaminated water. She spoke about the need for better roads in the area, the need for better education for children in her ward. She spoke and spoke, and I remained silent and patiently listened.

I have never experienced grief but I know that every heart deals with the loss of a loved one in ways that we cannot fully understand. I don’t know how a conversation about death of her child turned into a conversation about everyday problems, but for her it was all connected. Perhaps it is all connected. Maybe her children wouldn’t have died if their overall living conditions were more dignified. The way we hear about death in poor areas is starkly different from the way we hear we about death in upper class areas. Conditions of sanitation, access and economy greatly impact something like a measles outbreak.

Covering stories of the backbones of the city

Mumbai is known for its iconic kaali-peeli (black-and-yellow) taxis. Some of the most prominent political leaders have come up from taxi unions. Even though they don’t have the same power they used to, the drivers still turn to them when times are tough.

And times have been tough for the drivers ever since the COVID-19 pandemic. Writing a story on how the rising fuel prices are impacting Mumbai’s taxi drivers was a reminder of the kind of havoc the pandemic has left behind.

Read more: High CNG prices: Mumbai taxi drivers, auto drivers demand fare hike to survive

Many of the city’s taxi drivers have been driving for over two decades and are now old and frail. I remember interviewing 65-year-old Sain Ullah Khan, who earlier took an off every Friday and Sunday. But now the old man works tirelessly to make up for lost savings. He doesn’t take a single day off and is a diabetic patient with a chronic back pain.

Sain told me he doesn’t see himself retire because he still needs to take care of his house.

Sometimes I wonder whom we write these stories for and if covering stories make any difference to the lives of those like Sain, Mehrunissa or the Khilare family. I then tell myself that perhaps people are comforted in merely knowing that at least someone cares enough to stop and listen.

The caption to the picture showing Nana’s Chowk is “In 1991, there were 9.9 million people in living in Mumbai. Today, the city’s population is estimated to be over 22 million. Pic: Adam Cohn, Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)” To best of my memory, Greater Mumbai population in 1991 was 93 lacs, in 2001 it was 119 lacs and in 2011 it touched 126 lacs. Even if the decadal growth is considered as high as 25 lac, it comes to 151 lacs. The caption says 22 million ie 220 lacs. Even the 2011-2021 growth of 25 lacs mentioned is absurdly high. Why do journalists exaggerate the population numbers is a mystery I cannot figure out.