The Karnataka government launched the Gruha Lakshmi Scheme on August 30th in Mysuru. Under this scheme, Rs 2,000 will be transferred every month to the bank accounts of the woman head of every eligible family.

The state government claims that this scheme will benefit nearly 1.28 crore women across Karnataka, making it one of the largest monetary transfer schemes in India.

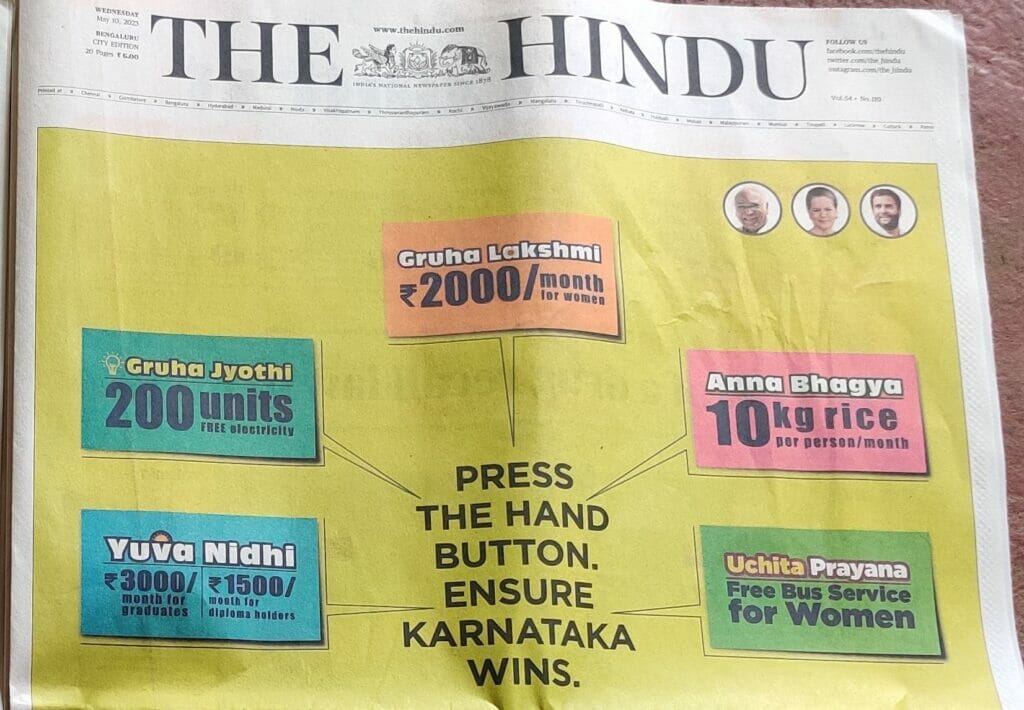

The scheme is part of the five guarantees by the Congress government. The five welfare schemes include:

- 200 units of free power to all households under Gruha Jyothi

- 10 kilograms of rice free to every member of a below poverty line (BPL) household under Anna Bhagya

- Free travel for women in public transport buses under Shakti scheme

- Rs 2,000 cash transfers to women under Gruha Lakshmi scheme

- Cash transfers to unemployed graduate youth under Yuva Nidhi

Read more: Here’s how you can access the five guarantees promised by the new Karnataka government

Who is eligible?

Women heads of households, who have either an Above Poverty Line (APL)/ Below Poverty Line (BPL) or Antyodaya card, and are not government employees or taxpayers are eligible for this scheme. The ration card must explicitly identify the woman as the head of the family. If she has a husband, he should not be a taxpayer.

Offline registration can be done at various centres, including Karnataka One, Bengaluru-one, Grama-one or Bapuji Seva Kendra centres. Registrations can also be done at the Gram Panchayat’s Office across panchayats in Karnataka. The scheme is implemented consistently across rural and urban Karnataka, with no changes in the operational modalities or the disbursed amount to beneficiaries.

Process for enrolling

- Women head of the families should visit these centres with the required APL/BPL/Antyodaya ration card and ensure that their bank accounts are linked to their Aadhaar card.

- If the Aadhaar card is not linked to the bank account, the bank passbook may be presented.

- Aadhaar card and ration card presented at the registration desk must be KYC updated. Without this, the application will not be processed. Additionally, the husband’s Aadhaar card is also required during registration. Once the documents are verified, the beneficiary is given a Manjurathi Patra, which serves a receipt/acknowledgment of the registration and bears the ‘Gruha Lakshmi number’. Having this number means that the individual has been registered under the scheme and will start receiving payments in their bank accounts.

- The same details will also be sent to the beneficiary via SMS on registration. In case there have been any recent changes in the ration card, such as updating the name of head of the household, there is a waiting period of one month before the updated names can be registered under the scheme, according to staff members at the Gruha Lakshmi helpline.

- The state government has issued helpline services for the citizens for any clarification regarding the scheme. People can SMS 8147500500 or can call the helpline number 1902.

Karnataka’s women empowerment

Karnataka faces significant challenges of underdevelopment, including poverty, environmental pollution, and disease, which are grounds for various diagnostic and reform-oriented interventions. Gruha Lakshmi, alongside other schemes, is one such effort aimed at tackling these complex problems.

With a click on the tablet, Rahul Gandhi, through direct benefit transfer (DBT), transferred the amount into bank accounts of the Gruha Lakshmi beneficiaries.

However, direct benefit transfer cannot be considered a silver bullet for the implementation of welfare schemes. There is a general inadequacy of the existing G2C (government to consumer) communication mechanisms under direct benefit transfer. This makes it difficult to address issues, including spelling errors in Aadhaar details, pending know-your-customer (KYC) verification, frozen or blocked bank accounts.

Under the Gruha Lakshmi Scheme, both women living in Bengaluru urban as well as the women household heads in rural Karnataka will receive Rs 2,000. However, the living costs are much higher in cities compared to rural areas. This essentially affects the impact that the amount disbursed will have on the household. Similarly, cities are known for precarious employment conditions. They also lack livelihood protection mechanisms like the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, 2005.

The state’s measure must be seen in the light of the upcoming national elections. What is the state government doing to strengthen the existing institutions? I analyse this question with respect to the banking infrastructure of the state.

Banking infrastructure

Implementing direct benefit transfer requires a robust banking infrastructure with last mile access. While the government relies heavily on direct benefit transfer, a comprehensive look at the banking infrastructure should make us question this reliance.

Out of 32,026 villages of Karnataka surveyed under Mission Antyodaya database, only 3,995 villages have availability of banks, that is, less than 12% of Karnataka villages have a bank available within the village itself.

Availability inadvertently affects how people access resources. The amount transferred to bank accounts has less relevance if the bank is not accessible.

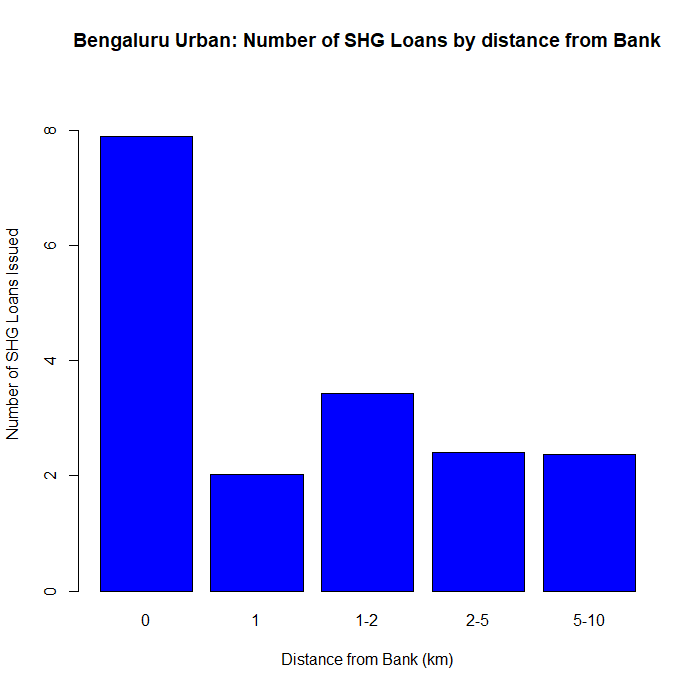

I analysed the Bengaluru Urban data for the number of Self Help Groups (SHG) loans issued and availability of banks.

Data Source: Mission Antyodaya 2020

As the distance of the villages from banks increases, the number of Self Help Groups (mostly led by women) accessing loans tends to decrease. Considering this condition of banking infrastructure, we must be sceptical of individual monetary transfers that are seen as the new face of welfarism. Deep fault lines of the welfare system cannot be solved through providing assistance to individual citizens.

These insights, coupled with the current state of banking in Karnataka, suggest a massive need to expand banking infrastructure in the state. Without a robust network of banks, all welfare programs from direct benefit transfer to availability of credit are affected.

Read more: Missing: ‘Anna’ in Anna Bhagya scheme

Healthcare for women

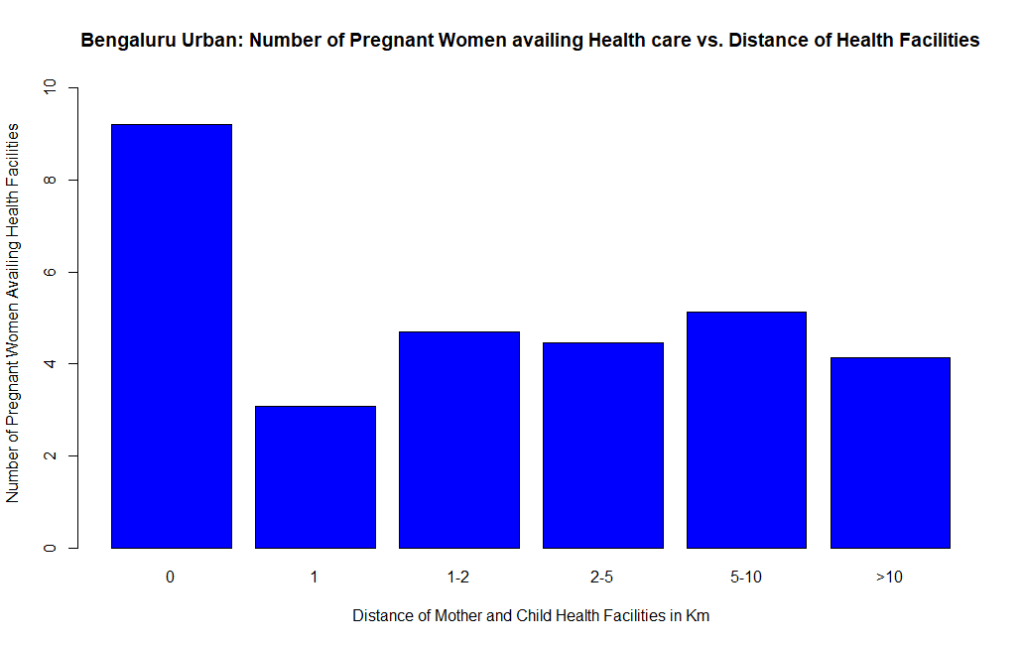

The availability of healthcare facilities for women is another key parameter of any credible social protection system for women. I analysed Bengaluru Urban data to look at availability of mother and child health facilities.

Out of 780 villages, only 190 have these facilities within the villages. That is, more than 75% of villages in Bengaluru do not have access to Mother and Child health facilities.

To highlight the spatial dimension of this deprivation, I compared the number of pregnant women availing health care services to distance of health facilities.

Data Source: Mission Antyodaya 2020

It appears that there is an inverse relationship between the parameters. As the distance from these facilities increases, the number of pregnant women seeking healthcare tends to decrease.

Given this uneven distribution of basic services, we must be skeptical of individual monetary transfers as a solution to holistic issues of public infrastructure.

Revising the scope of social assistance

What is the scope of social protection programmes? Are they transformative? While Gruha Lakshmi should be acknowledged for its scope, there are some lessons here as well.

Urban and rural context led approaches: A scheme this broad should have location sensitive implementation. Given the distinct infrastructural systems and income levels, the needs of urban dwellers are different from rural households.

Urban social protection designs that do not consider higher living expenses, rising informality and unemployment rates, income fluctuations, gender-specific and life cycle vulnerabilities, and inconsistent access to essential basic services, would likely achieve limited success. Similarly, the operational modes of delivery can vary for these two groups based on local infrastructure and requirements.

Public consultations: How is eligibility envisioned? Why is the amount Rs 2,000? A robust public consultation process is necessary for any long-term welfare programme. Lack of such measures can create tensions between stakeholders, as seen in the recent transport federation protests against the Shakti scheme.

Fiscal prudence: We must ask to what extent should stimulus packages be allowed to replace holistic development of the state? The latter will mean intensive investment in public health, education and the transport system.

Without this, the dreams of ‘Brand Bengaluru’ will remain an unfulfilled aspiration.

Do we know what % of 1.28 crores who are Graha Laxmi guarantee beneficiaries have access to banking facilities to receive DBT? It is shocking to know less than 10% of Anthodaya families have access to banking facilities. How will the rest get the funds transferred?

MY MOTHER’S GRUHALAKSHMI SCHEME 1 ST INSTALLMENT MONEY CAME BUT 2 ND, 3 RD, 4 TH, 5 TH, 6 TH, 7 TH & 8;TH INSTALLMENT MONEY NOT CAME OUR ALL DOCUMENTS ARE CORRECT EKYC AADHAAR LINKED SEDDING & NPCI MAPPING DONE SUCESSFULLY APPLICANT NAME -Shalinibai B Zingade, RC NUMBER – 510200176325, NAVANAGAR BAGALKOT REGISTERED MOBILE NUMBER -8431468091