India has, over the years, seen several schemes that promised free or subsidised medicine. In 2008, the then UPA government proposed a Jan Aushadi scheme for nationwide subsidised supply of generic drugs. However, there were not many takers for the scheme at the time. While some chalked it up to poor supply chain management, others believe heavy pressure from the pharmaceutical industry was the reason the scheme failed to take off.

Tamil Nadu had already established government stores in 1994 that provided certain drugs at reduced rates. But other states were slow to follow. Only some states like Rajasthan (2011) and Kerala (2012) initiated their own free provision of commonly used medicines at government-run hospitals.

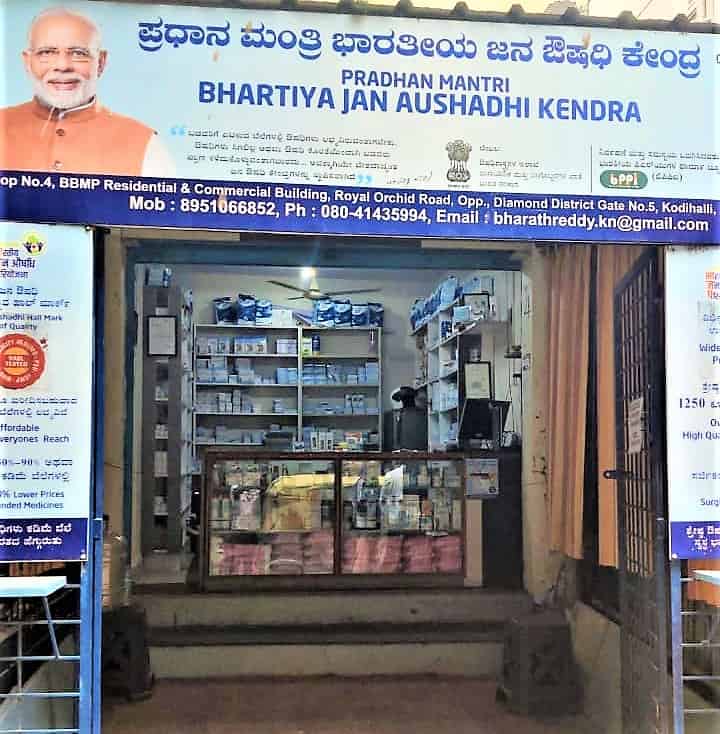

A year after the BJP came to power, the Jan Aushadhi Scheme was renamed the ‘Pradhan Mantri Jan Aushadhi Yojana’ before being rolled out as the ‘Pradhan Mantri Bharatiya Janaushadhi Paryojana’ (PM-BJP) in 2016. Approved by the PM-BJP’s Governing Council, Jan Aushadhi Kendras (JAKs) were set up to sell select generic and common drugs at up to 50%-90% of their market price.

Karnataka has had a shaky record of providing medicines at affordable rates to its vulnerable populations. The state-run Karnataka Drug Logistics and Warehousing Society procures supplies in bulk at lower costs and distributes it to district hospitals, medical colleges and other autonomous medical bodies.

Despite this, patients are frequently forced to purchase drugs that they should get for free in government hospitals. A scarcity of thalassemia-related drugs that are supposed to be free, and a daily-wage worker forced to cycle 300 km to Bengaluru to buy life-saving medication for his son, are just few of the stories that point to serious gaps in Karnataka’s public health system.

Karnataka has 915 official JAKs — second only to Uttar Pradesh (1122) — with 232 of these listed in Bengaluru Urban district. In the midst of contemporary India’s largest health crisis, how have these Kendras helped Bengalureans?

JAKs, an asset and a liability

While the world average for Out-of-Pocket health expenditure (healthcare expenses borne directly by patients/private households) is 18.2%, in India this expenditure stands at 65% according to its own Economic Survey (2020-21). This makes initiatives like JAKs an important public asset, believes Dr Upendra Bhojani, Director of the Institute of Public Health, Bengaluru (IPH).

Dr Upendra and a team of researchers conducted a large census covering over 9,000 households across Kadugondanahalli (KG Halli) in 2009-10. The survey found that, over a one month period, out-of-pocket spending on chronic conditions led to doubling of the number of people living below the poverty line. A second survey of over 1,000 households in the same area in 2012-13 found there was an increase in self-reported chronic conditions, especially diabetes and hypertension, with a majority of these patients going to the private sector which increased their healthcare costs.

“Any initiative which provides free or heavily subsidised medication is an effective policy instrument to reduce financial barriers in public access to quality healthcare,” Dr Upendra said.

Read more: “Primary healthcare should remain with BBMP”

Despite this, why do doctors in Bengaluru continue to prescribe branded drugs not easily available in hospitals or affordable stores?

According to Dr Upendra, one reason could be the profit-based relationship between some doctors or clinics and pharmacies. One pharmacist working at a Jan Aushadhi Kendra said that patients have actually come to return the drugs they bought because their doctor told them it won’t work.

“They will make them go and buy the same drug that is 10 times more expensive so that they get commission,” said one pharmacist (who wished to remain anonymous).

However, Dr Upendra also stated that certain practitioners prefer branded drugs in order to make it easier for migrant patients to find the drug they need in multiple locations. Dr Sylvia Karpagam, a public health doctor and researcher based in Bengaluru, said that many patients themselves believe generic drugs are less effective or less safe than branded ones.

Quality issues, shortages at Bengaluru JAKs

It hasn’t helped that recently quality control has been a matter of concern at JAKs. In February of last year, a child’s tongue turned blue upon taking an expired drug bought from a JAK in Bengaluru. Several unexpired drugs were then found to be unsafe and were consequently recalled. Over the past five years, batches of more than 50 drugs have been recalled from JAKs across the country.

One pharmacist working at a JAK in Bengaluru said they do face some quality problems. Showing a strip of tablets where one was broken inside the packet itself, the pharmacist said that even minor damages like this makes the drug useless as people won’t believe it is safe.

Dr Sylvia said it is very difficult to rebuild faith in a JAK after a drug sold by it has proven dangerous. Kendras can be life-saving for Bengaluru’s urban poor; but how will the poor reap its benefits if they don’t trust it? Strict quality control and supervision of manufacturers is an urgent requirement for the scheme to succeed.

Pharmacists working at two different JAKs in Bengaluru also complained of regular supply shortages. While one said that antibiotics and glucometer devices (used to check sugar levels) have been missing for more than a month in their stock, another said that multiple medicines, including commonly requested anti-diabetic drugs, have not arrived from the distributor in more than 2-3 months.

In fact, during my interviews with them, one JAK was unable to provide six out of the eight drugs from a patient’s prescription due to lack of supply. A few pharmacists said the lack of transparency between manufacturers, distributors, Kendra owners, and them is to blame. Kendra owners, who typically have no expertise in medical care, update suppliers about stock requirements. Pharmacists employed by the Kendra owners sometimes have no way of communicating with the owners or directly to suppliers.

“They [suppliers] send one month’s stock at a time,” said one JAK pharmacist “Within that month, there is no way to acquire drugs we have run out of. We have to wait for the next month. Even then, sometimes they supply material we already have but the missing stock remains unfulfilled”.

Top-down approaches such as these run the risk of not only making Kendras a dumping ground of unused medicines but also lessen their efficacy in the eyes of the communities they are supposed to serve.

“If someone needy comes into the Kendra and I have to tell them I don’t have what they want, why will they come again?” asked a local JAK pharmacist. “They will think this place never has the thing I need. Then the point of the kendra which is to help them save money gets wasted”.

There are also consistent irregularities with the stock they do receive. At one of the Kendras, a medicine was packaged differently in two separate deliveries despite being the same chemical, same weight, and having the same number of tablets.

“Sometimes packaging changes, other times the tablet’s colour. People who are not literate will get confused and not trust what we are giving because they will think that this does not look the same as what we gave before. It’s the same medicine but it’s hard to convince them because it looks totally different,” the pharmacist added.

No coordination between JAKs and state healthcare system

JAKs come under Karnataka’s Health and Family Welfare Department. Despite multiple attempts, I was unable to reach department officials for their comments on the condition of JAKs.

While some doctors working in low-income areas themselves come to Kendras to purchase drugs for their patients, bureaucratic facilitation is largely missing between JAKs and local healthcare providers.

Dr Prashant N Srinivas, Faculty and Assistant Director of Research at IPH, said that JAKs currently function independently of district health systems, often stocking medication already stored by the city’s public hospitals.

According to him, JAKs are unable to resolve the issues of drug non-availability. He believes there is an urgent need for improved coordination between JAKs, district offices, government hospitals, primary healthcare centres and workers, and district warehouses, to ensure that essential medication like antiepileptics and others that are usually out-of-stock in Bengaluru’s government hospitals can be accessed at JAKs.

Dr Gopal Dabade, President of the Drug Action Forum, Karnataka, has been running a JAK in Dharwad for over three years with an NGO named Jagran. He said that qualified pharmacists are key to a kendra’s smooth operations. He emphasised their role in convincing patients to overcome their drug hesitancy.

But the problem goes deeper. Dr Sylvia said that often even certified pharmacists hired by private pharmacies and JAKs do not have proper training due to lack of inspection of medical colleges. Even so, Dr Dabade said his patients who have diabetes or hypertension have reported saving almost half of their earlier expenditures on medication by visiting JAKs.

It would be a crucial misstep then for pharmacists working at JAKs to not have structured salaries. Currently, like other healthcare workers (ASHAs, ANMs), JAK pharmacists are not considered employees. Compensation for them depends solely on the Kendra’s owner. Some receive nominal salaries but some receive incentives and cuts from the services they provide; in this case their volume of sales. This, and the fact that JAKs are run by individuals or small companies with huge support from the government, could make the scheme an opportunity for misappropriation of funds.

“Expand free medicine programmes“

Dr Prashant of IPH said that independent researchers and Karnataka Health Systems Resource Center, a government body under the state’s Health and Family Welfare Department, should be conducting assessments and evaluation of the scheme, which can then be shared in the public domain. It would be difficult to resolve issues of stock and storage without a comprehensive understanding of whether the scheme-provided drugs are actually meeting the needs of the communities they serve.

In Bihar’s Nawada district nine JAKs that were registered and approved by the Governing Council (appointed by the Centre) had the same contact person listed. A journalist found that many of them were either not operational or had not even been opened. It is thus highly risky for the government to fund the semi-private purchase of medicines through the Kendras while not focusing on its own public provision of medication to impoverished patients.

Read more: “A digitised card cannot solve problems of access and affordability in public health“

The impetus, especially in the current time of grave crisis, should be to expand the scope of pre-existing free medical programs within the bounds of state-run hospitals. Why can’t arrangements required to help Jan Aushadhi Kendras thrive also be applied to the outpatient care responsibilities of public hospitals?

Dr Sylvia adds that market prices of branded drugs are unreasonably high; at times 200% above manufacturing costs. Not surprisingly, a majority of Bengaluru’s ever-increasing population saw their income take a serious hit during the pandemic.

According to a survey conducted by Azim Premji University last year, 46% of informal sector workers continued in the same job they had before the pandemic with reduced pay. Another 15% reported losing work entirely. In distressing conditions as these, the Kendras have been useful in limited ways. With the anti-diabetes pharma market alone reaching almost Rs 15,000 crore in 2018, it is clear why there is so little clamour for quality investment in free medicine.

Recently, a senior anaesthetist at a district hospital in Bengaluru was quoted in the Hindu saying that supply problems in the city’s hospitals stem from Karnataka State Medical Supplies Corporation Ltd not floating tenders for two consecutive years.

Going forward, free and not subsidised medicines should be on the agenda, said Dr Gopal Dabade. A study of over 2,000 domestic workers in Benglauru showed that 60% were not paid in the first national lockdown. It is crucial then that the city’s hospitals continue providing free medicine for those for whom a medical emergency can mean debt. What is meant to heal you cannot snatch away the food on your plate.

Dr Sylvia adds that the city must prioritise integrating Jan Aushadhi Kendras into Bengaluru’s government hospitals instead of letting them run as isolated pharmacies. Until then, the least that can be done is ensuring that those who need the important service provided by Jan Aushadhis get it on time and of the best quality.