As I climbed the stairs of the Velachery – Taramani link road Foot Over Bridge (FOB) at around 9 pm, I found myself in near total darkness as the FOB did not have any lights. The FOB has a roof on the top and sheets on the side, limiting light from the street entering it. Using the flashlight from my phone, I climbed further. Soon I found footsteps following me. A man was climbing the stairs behind me. Gripped by fear, I turned around, pretended to make a phone call and waited till he walked past me.

As I walked further along the FOB, I found many homeless people sleeping on the side. On the other end, close to where I was to descend, many men were sitting on the stairs smoking and talking. It was obvious from the smell that they were inebriated. The whole experience left me feeling very unsafe.

Once at street level, I noticed a couple of women trying to cross the same road through a small gap in the median. When I asked them why they were not using the FOB that was meant for pedestrians, their answer was obvious. “The FOB is not safe. Even during the day, it is unsafe as it is fully covered. I do not think anybody will be able to hear us if we shout for help,” says Ramya, one of the pedestrians.

“A couple of days ago two college students who were trying to jump over a median died after a lorry ran over them. Such accidents have become very frequent on this road,” says Selvam, who owns a tea shop near the FOB.

According to the 2021 NCRB report, Chennai ranks first among the highest number of road accidents among all metropolitan cities in India. Data released by Greater Chennai Traffic Police (GCTP) in 2022 also points out that 179 of the 508 killed in road accidents were pedestrians.

With increasing traffic congestion, pedestrians are given no space on the roads despite constituting a major part of road users. As a solution to pedestrian safety and safe crossing, the often proposed solution by the government is the FOBs.

According to the Greater Chennai Corporation web portal, there are as many as 40 FOBs in Chennai. However, given its many limitations, it may be time to rethink the usefulness of FOBs in the context of pedestrian safety.

Read more: Walking in Koyambedu, OMR or Chennai Central? Be cautious, warns study

Issues with FOBs in Chennai

Apart from the issue of safety, there are also many other pitfalls with the FOBs in Chennai.

For instance, Prakash, a wheelchair user says that the FOBs are not accessible for persons with disabilities (PwDs). “Often, the argument is that the FOBs will come with lift facilities to make it more accessible. But, in reality, we do not have the road infrastructure to reach the lift. Building a ramp does not mean, it becomes accessible for PwDs,” he says.

Sathyavani, a 60-year-old pedestrian says that FOBs in Chennai are not user-friendly, particularly for senior citizens. “Most of the FOBs do not have lift or escalator facilities. Even the ones that have escalators or elevators are not functional. This either leaves us no choice but to climb the stairs or to risk crossing through the gaps between the medians,” she says.

Tamilarasi, another pedestrian says that FOBs are not a good option especially when she has to carry heavy luggage and get across a road. “My destination might be just across the road but I will have to climb the stairs with heavy bags and get down. It is very tiring work to use the FOBs. Besides, as the FOBs are not very clean, it becomes hard for me to keep the bags down even to take a breath,” she adds.

Read more: Poorly designed foot over bridge in Guindy puts users in danger

“The constant use of facilities like escalators and elevators requires more maintenance. When the government plans for a FOB, they do not take into account the maintenance cost and the manpower required for upkeep. This leaves the escalators and elevators dysfunctional,” says Sumana Narayanan, Senior Researcher at Citizen Consumer and Civic Action Group (CAG).

“In some areas, people do not have a choice but to take the FOBs in Chennai. The reason is not that the FOBs are convenient but that the situation on the roads is very scary,” adds Sumana.

FOBs an unsustainable option for pedestrians

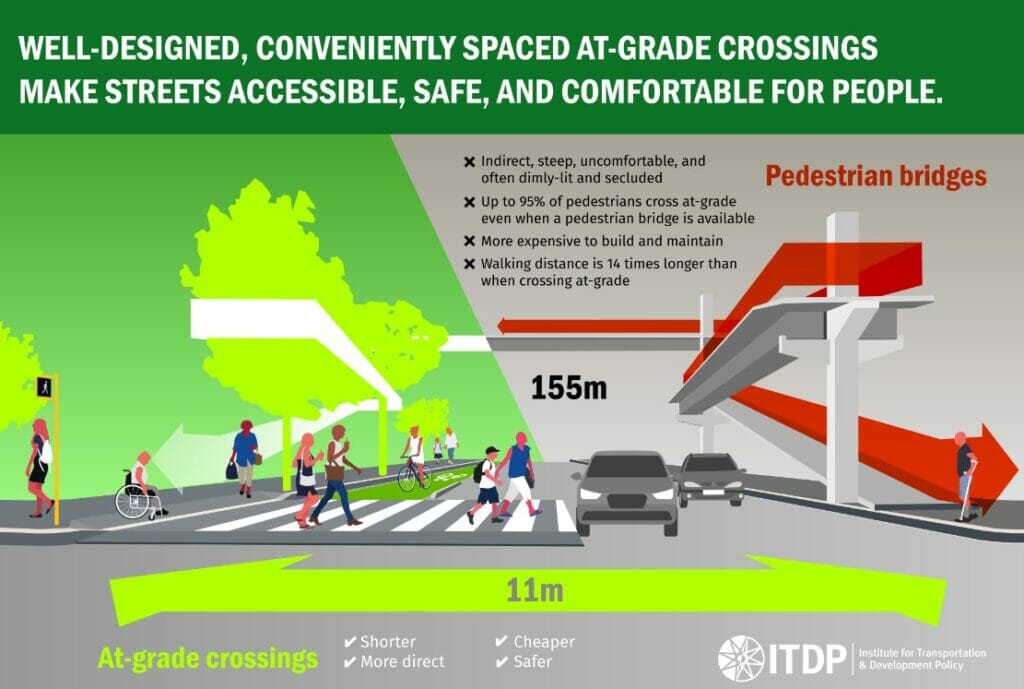

Smritika Srinivasan, Senior Associate, Urban Development, Institute for Transportation and Development Policy (ITDP) India says that FOBs are not a pedestrian-friendly concept by itself. “All our streets are primarily designed only for motor vehicles. There are other road users like pedestrians and cyclists as well. As the FOBs intend to ensure safety for pedestrians, the actual streets are not designed for vehicles to slow down when they see a pedestrian. This leads to a lot of accidents. We can see the pedestrians crossing at the street level or jumping over medians even in places where there are FOBs are installed,” she says.

FOBs usually do not work because of the way they are designed. “If someone has to cross a road that is 11 metres wide, they will have to walk more than 150 metres to reach the same spot through a FOB. It will also require them to take a detour from their path and put in more physical energy in climbing the stairs when their destination is right in front of them. This discourages the pedestrians from using the FOBs,” notes Smritika.

By extension, FOBs promote the speeding of vehicles despite the city having certain speed limits. Without providing the proper infrastructure to limit the speed of vehicles, pedestrian crossings in the form of FOBs turn counterproductive.

Smritika has also been doing a study on the FOBs in Chennai. “We also noticed that FOBs work when it is connected to some public transport stations, especially when its easily accessible from the concourse level. Otherwise, people use the FOBs when it is the only option to cross the road. For instance, when the medians are so high, they tend to take the FOBs. However, this is not the best-case scenario as it still encourages speeding of vehicles,” she adds.

Pointing out that OMR, which has over 10 FOBs – the highest number in Chennai – also has one of the highest pedestrian fatalities, Smritika says that no matter how many FOBs are constructed, people are going to cross at street level as it is easier for them. “It is high time that we start designing streets that will work in reality for the vulnerable road users,” she adds.

FOBs have not served the purpose because structures like this punish pedestrians just for being pedestrians.

“We have already invisibilised cyclists. In a consultation meeting for smart roads in Chennai, the officials once said that there are no cyclists in Chennai so they were not going to add cycle lanes. The same goes for pedestrians. By pushing them towards FOBs and subways, we have invisibilised them so that when the roads are widened the motor vehicles can speed freely,” notes Sumana.

Read more: Can imposing speed limits on Chennai roads make them safer?

Alternatives to FOBs in Chennai

The alternative to FOBs is designing better crossings at the street level.

“Pune, for instance, has been ensuring safe pedestrian infrastructure at the street level,” says Smritika. “The ideal solution will be to provide mid-block crossings at regular intervals so that the pedestrians need not walk too long to find a crossing to cross a street.”

Many junctions like Chennai Central and Nandhanam signals do not have a FOB. “This leaves the pedestrians with no option but to cross the road at street level where vehicles move very fast even before the signal turns green. As FOBs cannot be installed in all such junctions, at-grade crossing for every 200 meters is the only pedestrian-friendly solution,” says Sumana. “The at-grade pedestrian crossings should come with timers that give enough time to cross the road.”

A change in mindset is a prerequisite for all of this.

“When someone decides to take their motor vehicle on the road, they should be made aware that they will have to wait for the pedestrians to cross the road, give way for the cyclists and wait at traffic signals. It is the price they will have to pay no matter what. Otherwise, the solution for them is to use public transport. We are making the roads easier for motor vehicle users by building flyovers and FOBs and widening roads, long stretches without breaking for pedestrians. The focus should be on making the invisibilised pedestrians visible on the roads,” says Sumana.

Planning bodies such as CUMTA have made some strides towards planning while accounting for the needs of pedestrians.

“CUMTA also understands the importance of creating pedestrian networks and is actively looking to change the current dynamics. They are promoting sustainable transportation in which including pedestrians as a major street user is a key component,” says Smritika.

ITDP India has also prepared a guide to better street designs called “Better Streets, Better Cities: A Guide to Street Design in Urban India”. The guide begins with a discussion of sixteen street elements, such as footpaths, cycle tracks, medians, and spaces for street vending, covering the importance of each element as well as implementation challenges and design criteria. The guide can serve as a reference manual for municipal governments, practitioners, design consultants, and academic institutions. The guide can be downloaded here.

It is easier for me to walk 200 mts for the nearest street level crossing, than climbing up 20 ft on stairs. If I’m carrying any load, or if I’m aged it will be doubly difficult. If there is no nearby crossing I will take a risk by running across through the traffic and jumping over the median.