Karnataka usually receives southwest monsoon from June to September, and then the northeast monsoon from October to December. Any depression in the Arabian Sea or the Bay of Bengal can also cause additional rainfall. But in the recent past, rainfall patterns have been inconsistent and we are seeing a higher number of extreme rainfall events.

Rains this year have thrown life out of gear in many parts of the State, including Bengaluru. This calendar year, Bengaluru Urban district has received rainfall of 1128 mm to date. This is an excess of over 30% of the normal annual rainfall of 843 mm. Where does all this rainwater go?

Let’s look at Bengaluru’s geography to understand this. Bengaluru sits on a ridge, at an altitude of 920 m above sea level. The city is part of two sub-basins — Cauvery and Ponnaiyar. In the eastern part, rainwater runoff flows into the Ponnaiyar river sub-basin through Bellandur and Varthur tanks (which are part of the Koramangala & Challagatta valley) and Hebbal valley. In the western part, the runoff flows into the Cauvery river sub-basin through its two tributaries – the Vrishabhavati and Arkavathi rivers. Numerous tanks have been built on this course that spill over and eventually join the river.

Headwater streams

‘Headwater streams’ are the uppermost streams in the river network, which form the beginnings of a river and are furthest from its endpoint. Several such headwater streams join one another, and form parts of the river and stream networks. They play a critical role by trapping floodwaters, recharging groundwater and also carrying water to the downstream rivers.

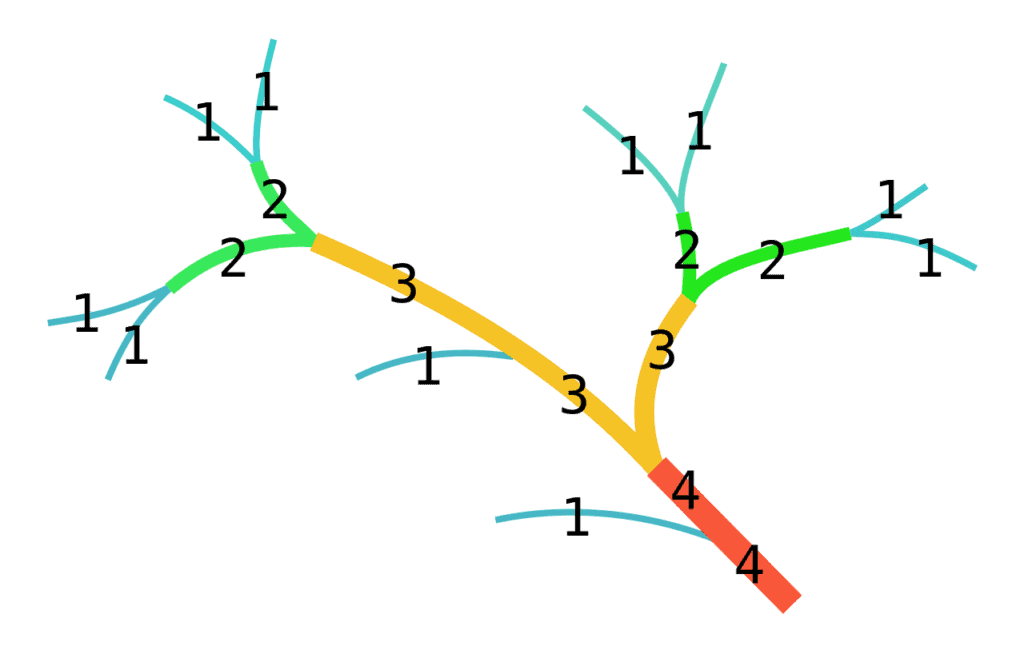

From a hydrology perspective, streams, tributaries and rivers are organised based on a hierarchical system called ‘Strahler number’. A stream flowing at the source of the river is usually the first order. When two such first-order streams join, they become a second-order stream. Similarly, several streams make up a larger one resulting in higher orders. A river could be seen when the stream is of the fourth or fifth order.

An example of a first-order stream in Bengaluru is a spring you could spot near Kadu Malleshwara temple in Malleshwaram. Before Bengaluru urbanised, such a stream would flow down naturally to higher-order streams. (Streams are different from roadside drains, which are engineered structures.)

Bengaluru’s natural streams have been engineered into drains

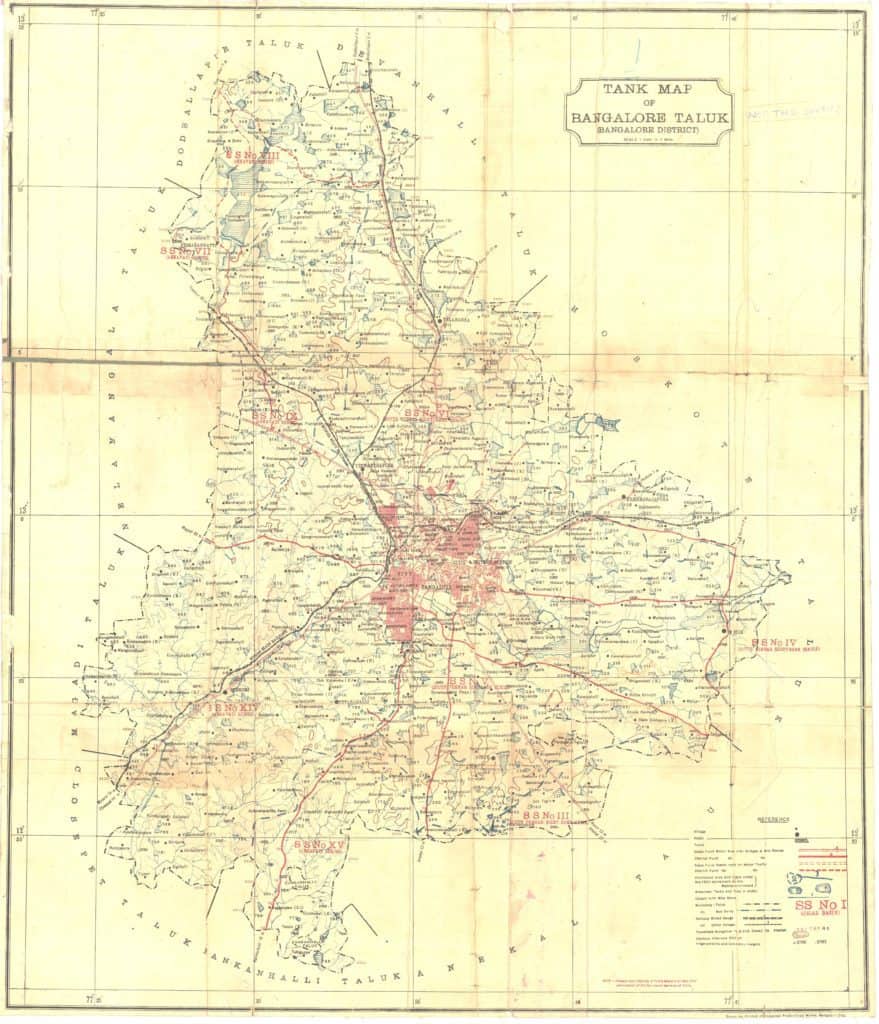

At Gubbi Labs, we undertook a study in 2014 to assess the status of headwater streams in Bengaluru. To establish the reference layer, we used the ‘Tank Map of Bangalore Taluk’ circa 1920.

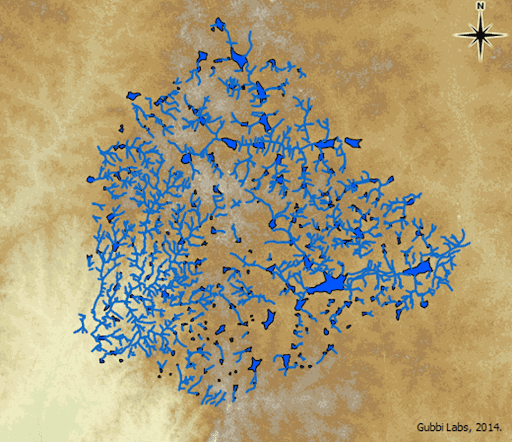

Using GIS tools, the tanks and streams were digitised to derive a map (below). The map revealed that, around 1920, the current BBMP jurisdiction had about 1309 streams with a total length of 793.8 km.

We further classified the streams based on their orders. The total length of all first-, second-, third-, fourth-, and fifth-order streams were 535.2 km, 181.6 km, 60.6 km, 8.6 km and 7.8 km, respectively.

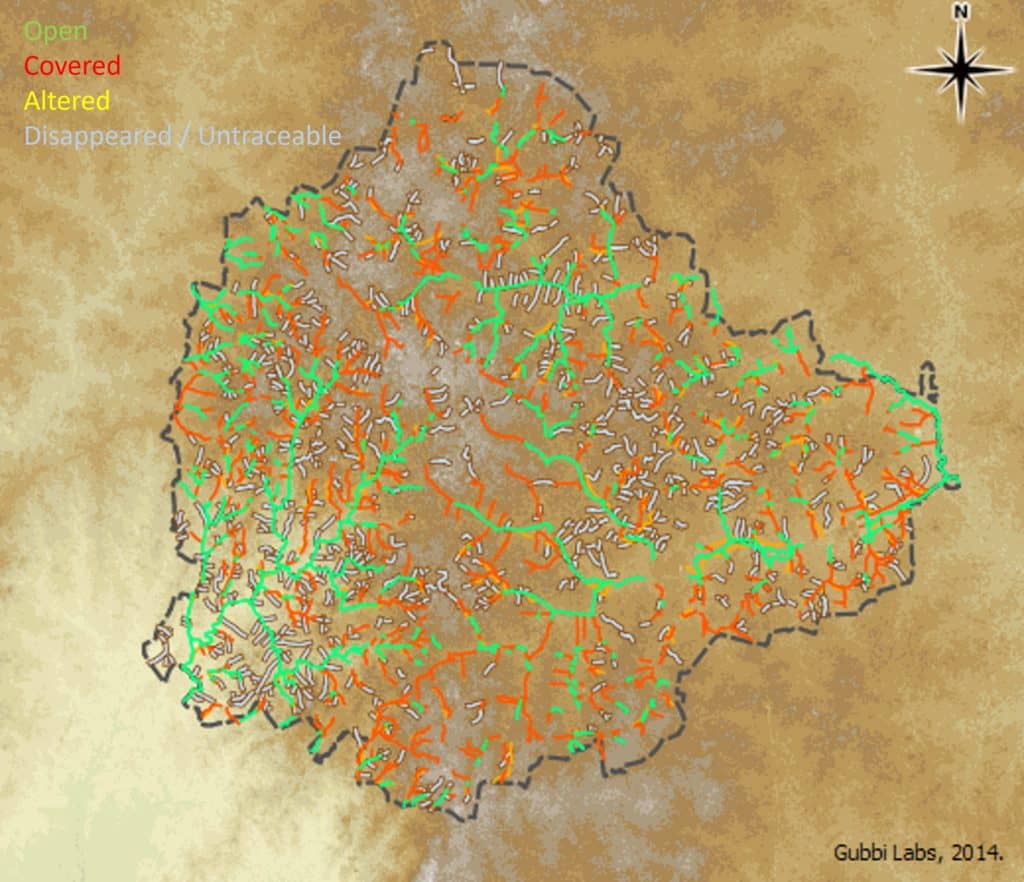

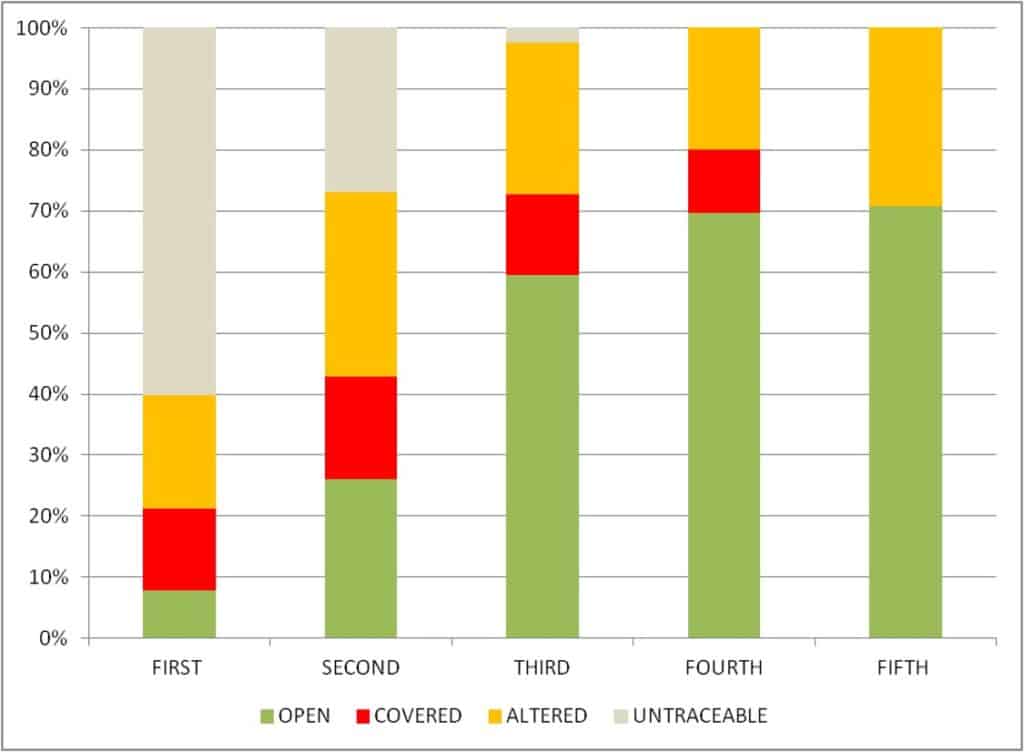

We wanted to find out what happened to these streams and tanks. Based on BBMP’s current Storm Water Drain map as well as satellite data from Bing, we categorised the current status of the streams (now also drains) as Open, Covered, Altered, and Disappeared/Untraceable.

The following map indicates the status of streams in 2014.

The analysis (see chart below) revealed that less than 8% of the first-order streams were open, about 13% were covered, 19% altered, and about 60% have either disappeared or were untraceable. About 27% of the second-order streams were untraceable. Though the third-, fourth-, and fifth-order streams remained, about 30% of them are either covered or altered, or both.

Stormwater drains are under the purview of the BBMP. They have conveniently ensured that several roadside drains lead to larger drains, which in turn lead to second- or higher order streams.

If the drains were channeling storm water alone, there is no reason for BBMP to intervene and build concrete structures over them. It turns out that Bengaluru has poor coverage of domestic sewage collection. This has resulted in households in connivance with BBMP letting sewage off into streams that have now eventually become drains. The Bengaluru Water Supply and Sewerage Board (BWSSB) is responsible for ensuring that sewage does not enter into streams, but has failed to do so.

With unchecked inflow of sewage into streams, BBMP is promptly attempting to conceal them as part of their ‘Master Plan for Remodelling of Storm Water Drains’, which is a recipe for disaster.

Also, several streams have been cut short or built over in the name of ‘development’. The severe abuse of natural streams by encroaching, altering and covering them through engineered structures is a concern.

In extreme rainfall events like cloudbursts, or even a continuous spell of rainfall like the one Bengaluru received a couple of months ago, rainwater will naturally flow wherever there is lower elevation, by following the natural drainage pattern – the first, second, third, and then the higher-order streams. At locations where the first-order or second-order streams are abused, naturally the run-off may not discharge into the respective tank, and the result would be local flooding.

Although there has been some effort to ‘protect’ Bengaluru’s tanks, unless the headwater streams are restored and conserved, proper inflow to and outflow from the tanks is not possible. Tanks can’t be protected only by securing their periphery; the first, second, third and higher order streams should also be restored and protected.

Read more: Surveying maps, roping in authorities and building a community for Bengaluru’s lakes

Legal conundrum

Let’s examine why so many first-order streams disappeared or became untraceable over a span of a few decades.

- No legal sanctity for first-order streams

First-order streams do not have legal sanctity like tanks do – as a parcel of land with a designated survey number. In other words, many headwater streams are not recorded in revenue records or maps; only higher-order streams like rajakaluves are.

This is because the Karnataka Land Revenue Act of 1964 doesn’t recognise headwater streams. In the absence of such recognition, any abuse of these natural headwater streams cannot be mitigated. Further, if one owns a parcel of land that has a stretch of first-order stream passing through, they are free to cover or alter it. Since there is no legal framework ensuring the protection of the stream, the person cannot be held liable for this.

Hence, an amendment to the Karnataka Land Revenue Act to recognise headwater streams, at least going forward, would be critical.

- State’s planning law too doesn’t recognise streams

A review of drain remodelling projects undertaken by BBMP and BWSSB reveals that they have been successful in engineering these streams that have now become drains. Thus, in many ways, floods in Bengaluru are an engineered artefact.

The State, of course, has an overarching planning law like the Karnataka Town and Country Planning (KTCP) Act of 1961. But, apart from being a dated law, it has several shortcomings on how a master plan needs to be prepared. (The Revised Master Plan 2015 is currently valid for Bengaluru.)

The KTCP Act doesn’t take note of headwater streams, but only land use. Importantly, the master planning exercise, done as per the Act, results in static, geometrically well-laid out plans without any forecasting capabilities. Instead of being a static document, a master plan should have dynamic land use forecasting (which is in vogue in the Netherlands). The system can also be open to the public so that everyone knows what changes are happening in which locations. This further calls for a new planning law that is responsive, dynamic and supports forecasting capabilities spatially.

Read more: How can policy and regulation help fix Bengaluru’s environment?

In this day and age, when almost everything around us has changed, what has not changed are our laws. The number of progressive laws is only countable in the past couple of decades.

While amendments have been made to many existing laws, at best they have been regressive (Akrama-Sakrama is a classic example). Thought leadership is needed in the political setup to bring out a foresighted law that can stand for a couple of decades, if not a generation. With the timeline of law-making narrowing down these days, it remains to be seen when and how such a well-thought-out law will be made to plan and protect the city. Until then, we have to bear the brunt of our legally-engineered streams causing floods.

dear sudhira this is a master piece work of you and your team, i hope the Bengaluru citizen will wake up and save nama Bengaluru