While roads and related infrastructure were given importance in this year’s state budget, housing, education and health were neglected. With the BBMP budget slated to be announced soon, Citizen Matters Bengaluru, organised a webinar, ‘The mysterious process of Bengaluru’s budget allocations’, on February 23rd, to raise questions about why some sectors are given preference over others, the source of funds, the format of the expenditure, and more.

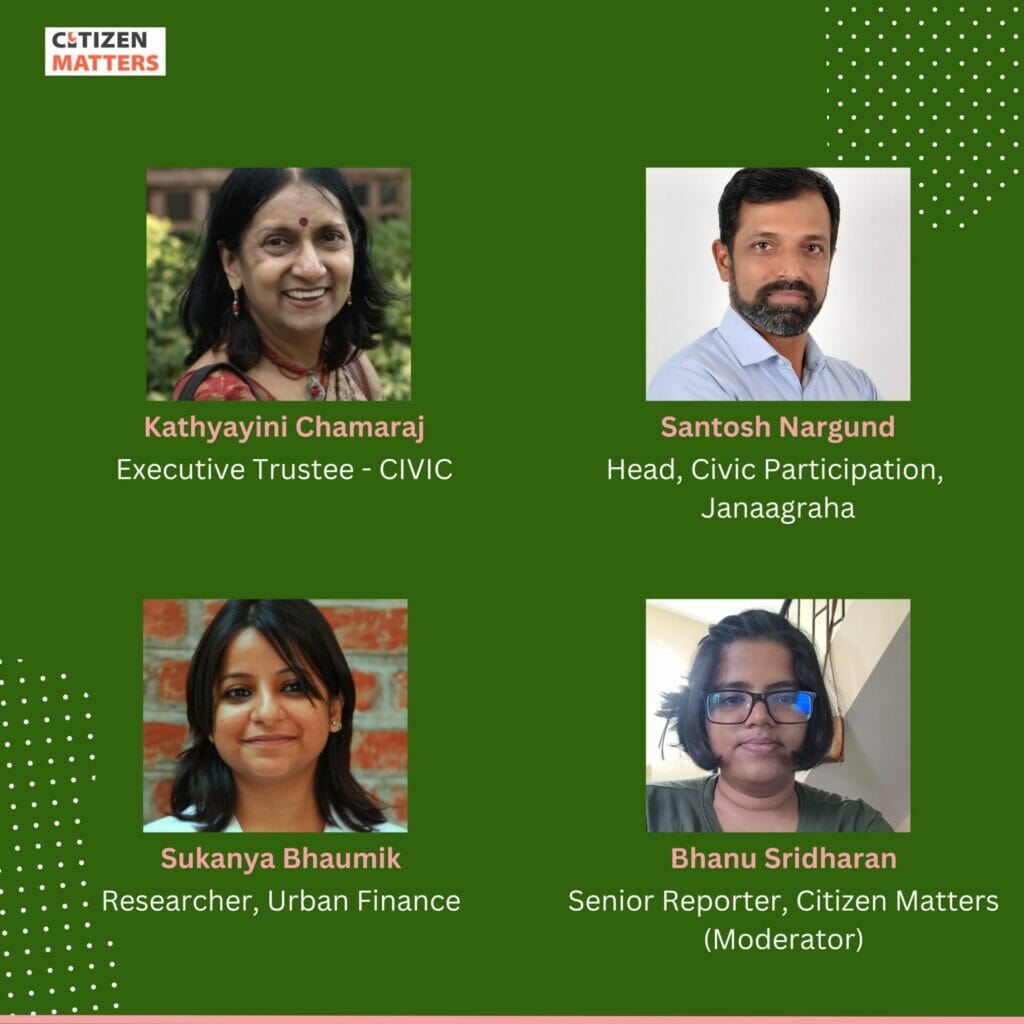

The discussion was anchored by Bhanu Sridharan, and the panellists were Kathyayini Chamaraj, executive trustee at CIVIC, Sukanya Bhaumik, an urban finance researcher, and Janaagraha’s Santosh Nargund, program lead- civic participation.

Rationale behind the process

Sukanya puts into perspective the decisions with regard to city spending. “If I were to analyse the 2021-22 budget, nearly 70% of the BBMP budget is for building infrastructure, 14% is solid waste management, 7-8% is for administrative expenses, and 5% remains for social infrastructure”. She adds that the budget is infrastructure-focused.

The BBMP budget estimates are prepared on the basis of past year’s figures and by following an incremental approach. “Under this approach, the previous year’s level of expenditure was assumed to be appropriate, taken-for-granted level of expenditure, and additional allocation was sanctioned as per pre-determined (thumb rule) incremental rate.” Generally a local body derives its incremental rates on the basis of an average annual growth rate.

“BBMP relies heavily on this incremental approach. This builds a bias towards continuing the same activities year after year, well after their relevance and utility may have been lost because of various reasons,” says Sukanya.

“For infrastructural projects, they consider the Detailed Project Reports (DPRs) and make estimates based on that for the current year. Additionally, there is very little connection between the current budget and the next year’s projection.”

Another issue is that the BBMP budget focuses on ‘how much’ rather than ‘how best’. “Everyone/department is more interested in how much money is being allocated to them rather than the appropriate and efficient way of spending it. This is the fundamental reason as to why BBMP has not looked towards reducing and realigning the budget estimates,” says Sukanya.

One of the greatest drawbacks of the municipal budgeting system in BBMP, says Sukanya, is the non-linking of financial outlay with physical targets/achievements. “Budget allocations are made in ad hoc financial terms only. Development works are undertaken from such ad hoc budget allocations any time during the year, are manipulated by socio-economic-political groups and vested interest groups, rather than executed as per techno-economic-social priorities.”

Read more: Karnataka budget focuses on roads and buildings, not on people

Bottom-up budgeting

Compared to other cities, Santosh says that the budgeting process for Bengaluru is better in terms of transparency, drafting budget estimates, etc.

“This year, we (Janaagraha) have conducted My City My Budget with a lot of civic organisations. It is a citizen-driven effort,” he says. Emphasising a bottom-up approach, Santosh says the BBMP in 2021-22 started making ward-level allocations based on citizens’ inputs. “It is a small amount compared to the overall budget, but this shows the in-principle acceptance of citizens’ input or bottom-up budgeting.”

We don’t have any evidence of any other city doing this, so we much acknowledge this, Santosh points out. He says we need to now focus on the ward development schemes, which are envisaged in the BBMP Act, 2020. “As per the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management Rules, 2004, we should draft a ward development scheme not just for a year, but five years down the line, ” he says.

The rules necessitate that the BBMP bring in financial discipline while making the budget, which BBMP has only recently adopted. “Complete adoption of the rules will lead to better streamlining of finances and better citywide development,” Santosh claims.

The bottom-up plan, Kathyayini states, has to be collated at the ward level and the ward committee has to be in charge of the ward plan, which will be under the purview of a Metropolitan Planning Committee (MPC).

The 74th amendment act

The state government’s control over the development of Bengaluru is in complete violation of the 74th Amendment Act, Kathyanini states. “The amendment mentions that a functional Metropolitan Planning Committee will create a vision plan for the city, which will act as a guiding document for all budgeting decisions.”

“The violation is that the state government still holds the reins of the budgeting for Bengaluru, whereas the vision of the entire 74th amendment is that the third tier of government, which is the BBMP council, should hold the reins,” says Kathyayini.

The 74th Amendment also directs that the planning should be for economic development and social justice. “If you are only talking about roads and waste management, where is the inclusivity? What about water supply and sanitation? What about health, education and childcare or social infrastructure for migrant workers and informal settlement-dweller?”

“There are a lot of schools, primary healthcare centres, and anganwadis that still come under the purview of the state government, and not BBMP. Hence by not activating the committee, the government is giving a skewed appearance to the budget, like it is meant only for roads,” she remarks.

Kathyayini says in rural areas, the devolution of powers to the third tier of governance has empowered the gram panchayats to draft effective plans. The roadmap has been laid for the rural areas, though not that much for urban areas. There has to be a similar toolkit for urban areas for going about fiscal planning. “The rules for the MPC say the committee is in charge of devising the rules for the BBMP to plan for the areas under its jurisdiction. However, the MPC hasn’t met or prepared the guidelines,” Kathyayini says.

“Citizens have to be allowed to participate in ward committees and area sabhas, where they can question the Councillors about the proper usage of funds,” Kathyayini says. The committee has every right to question the official about the projects that are being taken up in the ward, and the funds that have been disbursed for them. Once we know where the money is coming from and how it is being used, citizens should also be empowered to conduct social audits to bolster anti-corruption monitoring.

Issues in BBMP budgeting

Sukanya points out several other drawbacks:

- Unrealistic past figures: BBMP bases its budget estimates and allocations on historical figures, but the historical figures were themselves unrealistic. BBMP lacks data before 2008, when 110 villages were included within BBMP limits.

- Absence of overall targets/ceilings: Financial estimates and figures are budgeted without having any overall targets beforehand, causing heavy demand on sources of funds. Also, no proper detailed base work or calculations or analysis were made while estimating funds requirements or forecasting receipts of the BBMP.

- Excessive reliance on the type of deficit finance estimating: BBMP simply increases its revenue projections without any justification/tax raising steps/resource augmentation efforts. It just inflates the number. Thus, revenue estimates are always on the higher side.

- System of budget lapse: As a practice in municipal accounting in Indian cities, the unutilised budget allocation of revenue expenditure items lapses at the end of the accounting year. Lapsing of the budget meant less budget allocation in future. This encourages the tendency of BBMP to spend as much as possible and use up the budget instead of allowing it to lapse.

- Absence of proper financial estimating budget system: BBMP budgets contain financial estimates about labour cost, O&M expenditure, purchases etc, but these are not backed by detailed workings about the quantity of raw material required, standard quantity requirement, price per unit etc. These estimates are also prepared by following the rule of thumb, hunch, average growth rate, and incremental approach. This makes it impossible to carry out a cost analysis of expenditure estimated and actually incurred.

Watch the full discussion: