“Will the protection of Ennore and Pulicat wetlands alone bring them back to the time when they were clean and unpolluted?” asks K Saravanan, a fisherman from Urur Olcott Kuppam, who has also been mapping fishing villages across the city. “It is too late for a complete revival.”

In the wake of Pallikaranai marshlands receiving the Ramsar tag this year, the question on everyone’s minds is whether other wetlands in Chennai, like the Ennore and Pulicat wetlands, also get Ramsar status.

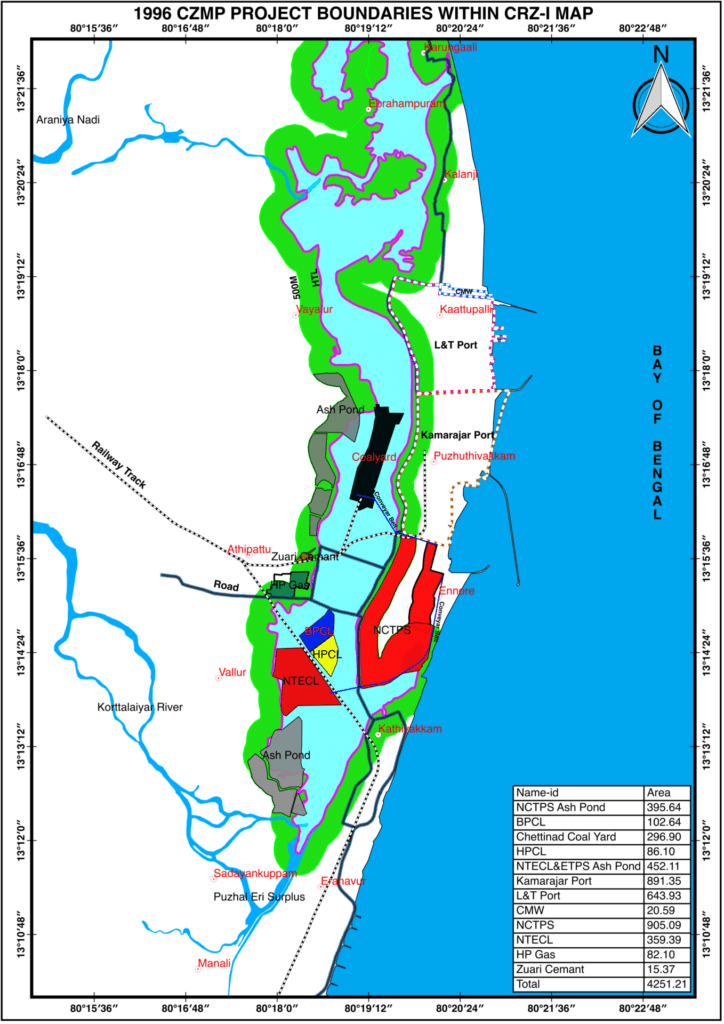

To examine this possibility, it is crucial to understand the causes and effects of the degradation of the wetlands. There are three ports and 36 red-category industries across the Ennore-Manali region, which pollute the air, land and water of North Chennai, including these wetlands.

Proof of Ennore’s degradation

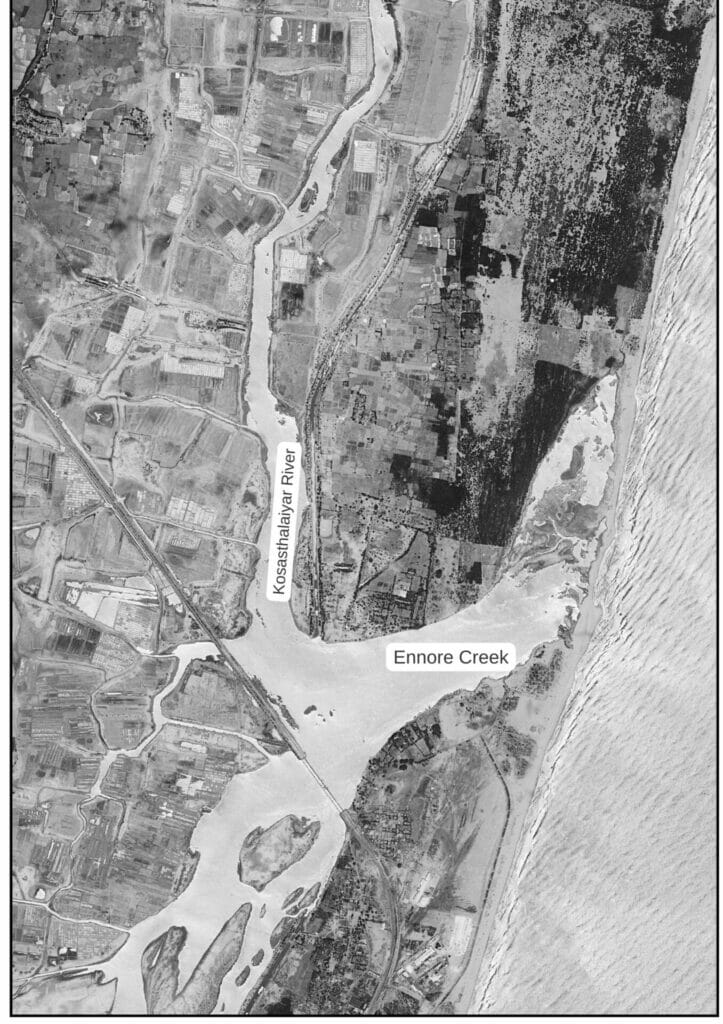

The oldest map of Ennore creek available goes back to 1965. “NASA took these photographs using a film camera from a hot-air balloon,” recalls Saravanan, as he shows the oldest photo of Ennore creek in the office of the Vettiver Collective, a volunteer collective working on environmental justice.

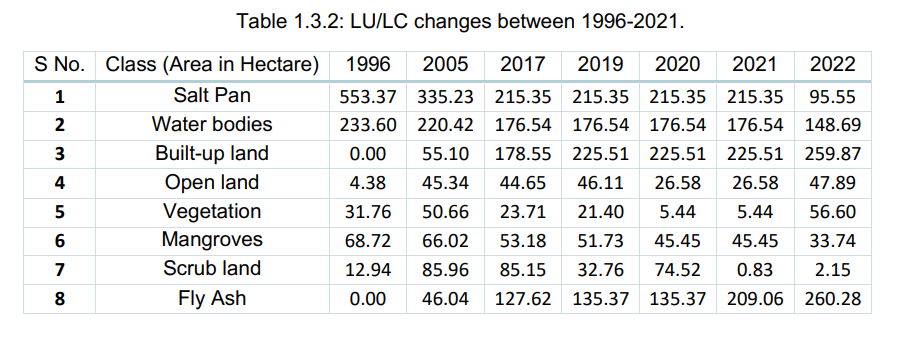

This map has confirmed that over 300 acres of river, canal and waterbodies have been polluted due to fly ash dumping, as per a National Green Tribunal report, as of 2017. It was identified that the North Chennai Thermal Power Station (NCTPS) is the major culprit in illegally dumping fly ash in the creek.

Read more: Ennore backwaters an “environmental crime scene” as fly ash dumping and encroachment continue

The Coastal Management Plan of 1997 also paved the way for more industries to crop up. “That management plan illegally erased the presence of Ennore Creek. Three kilometres of the extent of the wetlands were missing,” says Saravanan. This map was formed without the nod of the Union Government, as required under the notifications of the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change.

Wetland areas were eaten up for developmental projects, according to an expert committee report, as directed by the southern bench of NGT.

However, in the 1996 Coastal Zone Management Plan (CZMP), there were 16 kilometres of the stretch, which included Ennore Creek. This CZMP followed Coastal Regulation Zone-1 rules, where no developmental activities can take place.

In 2021, the National Green Tribunal intervened and asked the Coastal Zone Management Authorities of the state and union governments to adhere to the 1996 CZMP with modifications. “We consider the 1996 map to be the legitimate one. The 1997 map was used to bring about hazardous and polluting industries, supported by the state and union governments, among other private entities. Now, we can only save what is left,” says Saravanan.

The case of Pulicat wetlands

“Pulicat is a readymade candidate for Ramsar tag,” says Jayshree Vencatesan, Managing Trustee of Care Earth Trust, an environmental NGO. She has also contributed to the expert committee report.

A greater part of the Pulicat wetland lies in Andhra Pradesh, and a small portion lies in northern Tamil Nadu. For Pulicat to become a Ramsar wetland, both Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh governments must collaborate and make the application, suggests Jayshree.

“Apart from the [protected] Lake Bird Sanctuary, there is also an area owned by the Indian Space Research Organisation [Sriharikota] in Pulicat. There are also sites of historical importance like the lighthouse in the area.

“Moreover, because of the continuous availability of fresh water, Pulicat has been an agrarian landscape where people also fish. This is according to my personal assessment,” says Jayshree, adding that if the freshwater gets tampered with, due to upstream issues, then the landscape will lose its character.

Pulicat also satisfies all the nine criteria of being a Ramsar site, she notes. “A wetland can become a Ramsar site if it ticks just one criterion,” says Jayshree.

Read more: Ramsar Tag secured, what is the way ahead for the Pallikaranai marshland?

It becomes even more important to restore Pulicat since it generates the highest economic value among major wetlands in Tamil Nadu.

“But we cannot look at Ennore and Pulicat separately, since they are close to each other across the same coast. If we pollute one, the other also gets affected,” says Saravanan.

The fly ash that is dumped in Ennore by industries, travels in the water currents and causes skin diseases, confirm the fishermen of Pulicat.

“Once the wetlands are affected in a negative way, the damage is irreversible,” says Jayshree. “We are at a point where something has to be done [to restore] Ennore. If we fail to do so now, we will not be able to do it at any time. The changes will be permanent.”

Restoring Ennore wetlands will take time

“In Ennore, a lot of work has to be done for it to be considered a Ramsar site, because it has degraded greatly,” says Jayshree.

The expert committee report on the same gives a non-exhaustive list of work that need to be done to restore the Ennore wetlands. Some of the recommendations are:

- to bring back local species of flora and fauna

- to restore oyster beds/reefs after consulting local fisherfolk

- to bring about a proper waste management plan

- to bring about flood mitigation plans in the upstream regions

- to plan to prevent pollution from fly ash ponds

“As it stands today, it cannot become a Ramsar site,” says Jayshree. In other words, it does not meet even one of the criteria of Ramsar sites.

The future of Ennore creek

Even with the protections offered by a Ramsar tag being a distant dream, there is still some hope for Ennore Creek. The Tamil Nadu Wetland Authority plans to deem the creek a protected wetland under the Tamil Nadu Wetland Mission.

After taking up work like dredging and clearing up debris, the State Wetland Authority plans to start work to make Ennore Creek a protected wetland.

But the fisherfolk of the Ennore-Pulicat wetlands have been wary of the proposal of Kattupalli port expanding for more than 6000 acres, with 2000 acres of sea converted to land. “The sea intrusion will increase due to erosion, and Chennai’s flood risk will increase more,” notes Saravanan.

“When Ennore creek becomes a protected wetland, it will be a good policy tool to stave off the port expansion,” says Saravanan.

Saving wetlands can also save people’s health and livelihoods

“It was profitable to fish in the waters of Ennore until 2000. There used to be representatives from industries and ports asking us if we wanted to come for work there. But my father used to deny their offer, saying that he is fishing for a living. But today, that is not the case,” says Parthasarathi, a resident of Thalankuppam. He is a daily wage worker, and fishes only on holidays.

“When we used to fish, we would earn even Rs. 50,000 per month. People who work at the ports make peanuts,” says Parthasarathi. “The pollution in the waters has reduced the fish biodiversity as well.”

The expert committee report cites that white prawn, black prawn, sand whiting, sea bass, green crab and other fishes, locally known as Kalavan, Udupathi, and Oodan among others have disappeared or become fewer than before.

“Salt pans have also been encroached on by development activities. People used to take up work there during the summer months,” says Saravanan.

Apart from livelihood, the pollution in the wetlands has also affected the health of the locals. Fisherfolk, when exposed to polluted waters in the waters of the Ennore and Pulicat wetlands, may get skin diseases, and even cancer, in rare cases.

According to the expert committee report, children face a risk of getting cancer more than adults, due to getting exposed to lead, cadmium and copper in the polluted Ennore backwaters. The pollution’s ripple effects have caused a rise in their healthcare expenses, notes the report.

A Ramsar status must not be the sole motivation to restore Ennore and Pulicat wetlands. However, the health of the wetlands will be gauged internationally, and this can prevent further degradation of the wetlands by public and private entities.

Moreover, Ennore-Pulicat wetlands play a major role in mitigating floods through the natural resilience offered by them. With Chennai being in the eye of climate change, the Chennai Climate Action Plan draft projects that the city will face inundation in 56.5% of the area within Chennai Corporation limits in 100 years. Measures to protect the wetlands will also play a part in protecting the future of Chennai.