The basic necessities of democracy are timely elections, as well as formation and continuance of an elected government without any delays or truncated tenures. The idea of ‘one nation, one election’ has caught the attention of the people as the Government of India wants to adopt a policy of simultaneous elections across the country. It has formed a high level committee (HLC), headed by the former president of India, Ram Nath Kovind, to examine the matter comprehensively and make recommendations for holding simultaneous elections to the Lok Sabha, the state Legislative Assemblies, the Municipalities and the Gram Panchayats.

Even though the government has taken a comprehensive view and included all tiers of governments, the spotlight has been on the elections to the parliament and the state assemblies, which constitute about 0.15% of the total elected offices or seats in the country. There is, however, another important dimension to be considered – that of the third tier of governance in the cities (and villages) of India, which was established as an instrument of decentralisation of power and decision making. The situation at this large base of the pyramid of the republic is alarming.

Read more: Our city governments are very weak, completely at the mercy of the state: Yogendra Yadav

Critical issues in election and formation of local self-governments

Over 95 crore voters of India elect 543 members of the Lok Sabha (MPs) and over 4,100 members of legislative assemblies (MLAs) of various states. The same voters elect over 87,000 councillors representing the wards in India’s municipalities and corporations in over 4,800 small and large towns and cities, and over 3.1 million members of over 2.5 lakh gram panchayats (GPs) across the states and union territories of the country.

Article 243U of the constitution of India, introduced by the 74th Constitution Amendment Act, 1993, mandates that the election to every municipal body shall be completed before the expiry of its normal term of five years, just as for the state assemblies or the Lok Sabha. Hardly ever has this provision been implemented in letter or spirit by the different states.

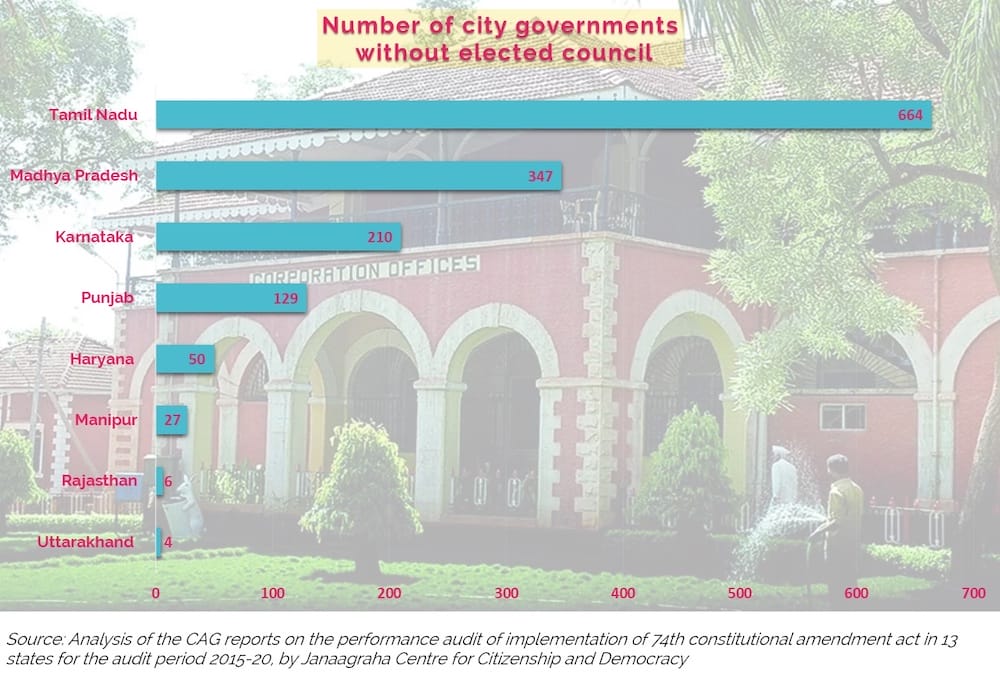

A study of the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) of India’s recent performance audit reports on the implementation of the 74th Constitutional Amendment in the states of Haryana, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Punjab, Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu and Uttarakhand, reveals that 1,437 municipalities had no elections on time to their city councils. Tamil Nadu topped the chart with 664 of its municipalities having no elections on time, while Madhya Pradesh with 347, Karnataka with 210, and Punjab with 129 of their towns and cities with no elections, followed closely behind.

The Supreme Court and the High Courts of various states have, in different cases, particularly in the Suresh Mahajan Vs State of Madhya Pradesh (2022), ruled that under no conditions are elections to municipalities to be delayed. Therefore, in the case of municipalities or the urban local bodies (ULBs), the matter to be examined is more about conducting elections itself or conducting elections on time, than that of conducting elections simultaneously or otherwise. Any reform that brings with it the promise of elections to the ULBs without any delays is welcome for the 400 million plus city dwellers of India.

Read more: Opinion: Amendment to law on Delhi governance retrograde and regressive

An autonomous framework missing in action

Unlike the elections to the parliament and the state legislatures, which are organised by the Election Commission of India (ECI), the constitution provides for a State Election Commission (SEC) in every state for superintendence and conduct of elections to municipalities and panchayats in the particular state. The state legislatures are, however, authorised to make laws in all matters relating to elections to the municipalities. Thus, many state governments have undermined the SECs, by assuming their functions to conduct delimitation of wards and notify elections on time. The result has been no guarantee of elections every five years in our municipalities as mandated by the constitution, as seen from several examples quoted above. Further, it also leads to partisan considerations in delimitations and caste-based reservations, which, invariably, end up being challenged in courts, leading to endless delays in conducting local elections.

The failure to conduct city elections on time leads to state governments directly running the administration of the cities, resulting in reversal of the decentralisation of governance at the local level. The tendency of not conducting local elections regularly at the five year intervals is so common that even the largest and the most well-known cities of India wait for years for elections to be conducted after their council terms expire.

In the latest round, the Greater Chennai Corporation had elections in 2022 after a gap of nearly six years, and the Municipal Corporation of Delhi had elections after a delay of seven months, while the financial capital, Mumbai, and the tech city, Bengaluru, are still waiting for elections for 1.5 years and three years, respectively, after the expiry of the term of their previous councils.

Another area leading to breaking the sequence of regular and simultaneous elections is due to certain constitutional and statutory provisions of municipal administration that entrust the state governments to schedule the date of the first meeting of the city council, from which time the council’s term of five years begins.

This provision has resulted in state governments notifying the date for the first meeting of the elections to the city council even months and years after the results are declared by the SEC. This practice, while breaking the sequence of elections, also virtually negates the mandate delivered by the people through the elections.

Need for reforms

Cities are the engines of economic growth and abode of more than a third of the population of the country. Cities not only fuel higher national output in terms of GDP, but also are the place where most of the development programs of the central and state governments are implemented. While the MLAs and the MPs play the role of legislating and participating in the governance of the country and the states, the councillors of city municipalities play a critical role of being the first-mile democratic connection with the people. Whether it is identifying new civic projects such as roads, drainages, parks or street lights in the neighbourhood, or resolving local issues of water supply, water logging or garbage collection, or providing succour in times of calamities and public health emergencies such as the covid pandemic, the councillors place themselves among the people, and monitor and guide the works.

Councillors are the local leaders, whom the people can access much easily for their development requirements as well as for redressal of local problems, and look up to them to voice their concerns within the government.

Not having an elected councillor in the ward is like missing a friend in need. It is essential to fix our city governance systems, to aid the realisation of the government’s vision to fast track economic progress to make India the third largest economy of the world, with a sharp focus on local action for the 21st century human development priorities of environment sustainability, primary healthcare and livelihoods.

A firm step in the direction to realise these goals is to devise mechanisms that will not only institutionalise on-time elections to the municipalities, formation of city councils without delays after election results are declared, and a fixed and full tenure of 5 years to the city councils, but also ensure accountability of the institutions concerned.

Arriving at a definitive framework to achieve the above objectives, with the necessary amendments to the constitution and the statutes, in tune with the spirit of federalism, will be the challenge before the HLC, the parliament and all the stakeholders.

(The views expressed are the author’s own)