Gayatri is pursuing her Masters in Law at the University Law College in Bengaluru. After finishing her graduation, she thought that doing a masters degree would help her job prospects and career. Coming from a family of daily wage labourers, Gayatri wanted to uplift her three siblings too.

Covid-19 arrived, affecting her in more ways than one. To start with, she hasn’t been able to pay her fees of Rs. 46,250. Unsure of whether to ask for funds from public donors, she shared her problem with a few student activists.

Gayatri is not alone. Several students in the city — boys and girls — from poor backgrounds, unable to afford college fees, are at a crossroads in their studies. As the pandemic and the economic slowdown affects their parents’ jobs, livelihoods and incomes, children’s education is becoming one of the first casualties.

We spoke to a few girl students pursuing PUC, under graduate and post-graduate studies. For many of them, education is the ticket to a job, career and independence. But when weighed against the financial troubles brought on by the pandemic, their families would sooner consider their education dispensable.

Many of these girls received help from friends, teachers and well-wishers. Some others received concessions or extensions from their institutions. But in the absence of a government-backed initiative, it is unclear how many of them can hang on longer.

Extended uncertainty

Initially in March and April, when no one knew how long the pandemic would last, institutions were flexible. They delayed exams, results, promoted students, gave concessions, allowed late payment of fees and so on.

Colleges even began the new academic year in June and pushed through the first semester, almost entirely through online classes. They did not change their fee structure, but some of them gave a few students concessions by ways of extended deadlines.

The situation has since worsened. As the year came to an end, it is now clear that the effects of the pandemic — with fears of a second wave in January-February — could be prolonged. Even help from individuals and concessions from educational institutions appears to be dwindling.

Education is redemption

“I am now with family in Kolar and trying to see how funds can be arranged. I have three siblings and my parents are daily wage workers. We can’t afford the fees any more because of no income,” says Gayatri. She is not sure about what to do next.

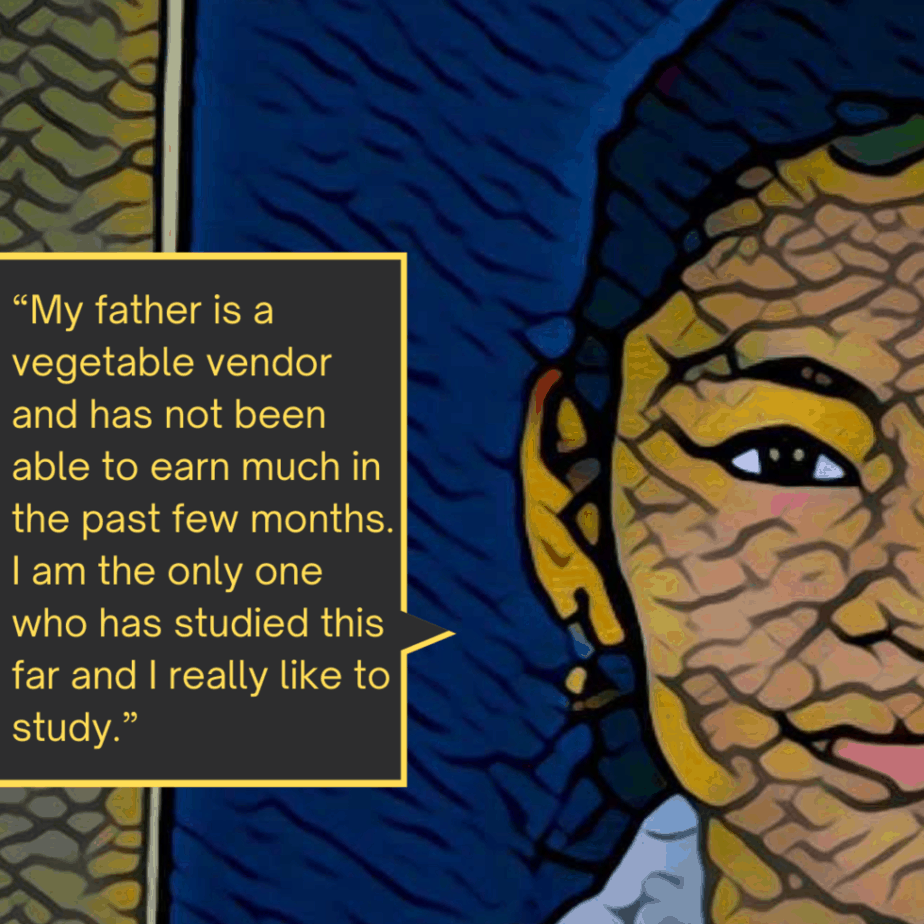

Shama (name changed) is a pre-university student and her appeal for funds says she has discontinued her studies for this year. Her message has been circulated in WhatsApp groups in known circles.

The 17-year-old wants to study for three or four years more to become what she wants to be, a bank officer.

Her college had given her a deadline of January 10 to pay the fees. Of the Rs 29,000, she has been able to pay only Rs 11,000. Without paying the full sum, Shama may not be able to appear for the PU exams. “I don’t know how to continue. My family is asking me to take a break but I don’t want to. I don’t know any other job to support my studies right now,” she says.

Similarly, Shreya, who is in her third year degree, has only paid part of her fees and needs to complete her course. Her sister and she look after their mother who doesn’t keep well. Her appeal for funds was also circulated by a fellow student.

“My sister has been trying to support us, but my mother is not keeping well and there are so many expenses. If I could just get through and complete my degree, I could also start some work,” says she. “I don’t want all my efforts and family’s efforts to go to waste, it’s my last year. I hope I can complete this year somehow.”

None of these students have made it to official figures yet, as the enrolment numbers are not yet consolidated and released. Also, some students are taking a gap year while some have applied for extensions and concessions on fees.

Meanwhile, reports indicated that owing to higher fees in private collages, there has been an increase in enrolments in government schools across the State.

Intervention as policy

Different colleges are reacting differently to the situation. From counselling and flexible exams, to extended deadlines for fee payment, colleges are trying to retain students. Fee exemption, however, is not one of them.

Fees in private colleges ranges from around Rs. 25,000 to Rs. 60,000 per year or even more in cases of some professional courses.

Dr. Melwin Colaco, registrar of St Joseph’s College, said students in the college come from deprived backgrounds and that many of their parents had lost jobs in the pandemic. The college did not reduce fees, but the student’s union started a drive for crowdfunding. That helped a few students, he said.

Apart from fees, online classes and examinations have brought about more challenges such as access to internet, laptops and smart phones, he said. A few lecturers revealed that some students reached out for emotional support as well.

Naureen Aziz, Department of English, Jyoti Nivas College says that the college started many initiatives to help students cope with the pandemic, such as payment of fees in multiple installments, mentoring and counselling programmes. They also had book bank from where students could borrow books for the academic year.

Organisations such as Students Federation of India are looking into individual cases. K Vasudev Reddy, SFI’s state general secretary says, “We don’t do fundraising as an organisation but we are trying to help.” Most of those seeking help want to complete college and take up jobs, he said adding “but there are no jobs”.

“Things will get better”

Higher education minister Dr. C N Ashwath Narayan told Citizen Matters that the government is rolling out several measures to make online education easily accessible. “OBC and SC/ST students get a refund of their fees even for private colleges. We are trying to make exams and lessons easily available. I know this has been a very difficult time but the students should try to cope because it is about their future. Things will get better. But if they dropout, it will have a lifelong impact,” he said.

The government is yet to assess the drop-out rate in colleges, but would unveil plans to make things better for students, he said. “The youth are the future of the country. If they do well, the country will do well,” he said.

Needed: Proactive helpline

Activists groups and individuals have raised money and support for individual students as and when they are approached. They have even tried to source funds in the public domain. This, however, has not been sustainable.

In the absence of helplines and centralised efforts, students are reluctant to share details. In many cases, they have — like Gayathri — returned to their native towns and villages. Also convincing individual donors has been an issue, the students say.

The students say they would be more comfortable to approach for help had there been counselling centres in their colleges or university campuses that could guide them. Many also wanted counselling to manage stress, they say. A well-thought-out plan for fee structures, payments, scholarships and disbursal of funds would go a long way in ensuring they stay on course.

Reddy says there is a chance that many adolescents and youth will be pushed into informal labour work and may not be able to return to studies. If the appeals of these students, the coming academic year will be a challenge for many.

“It is important to focus also on the mental health of students. We need to be more empathetic and focus on keeping them engaged and motivated rather than on grades. Financial difficulties apart, they are also facing emotional challenges and anxiety issues. Screen time is one of the reasons of increased anxiety among some students. We are still not sure about opening in the coming academic year and everyone misses the interaction but we have to find ways to keep the students going. We have to be mentors and not just teachers,” says Naureen Aziz.

Also read: