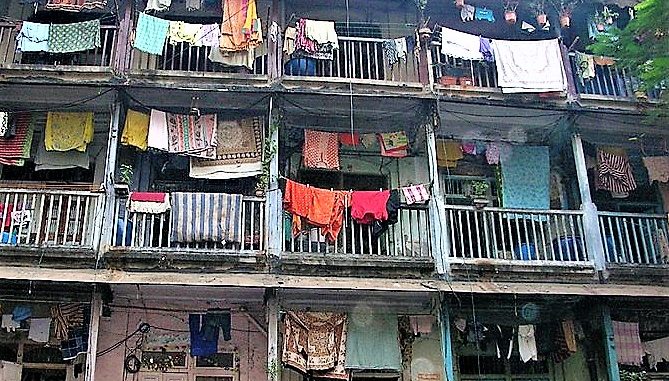

Every year, some buildings give up the fight against Mumbai’s harsh monsoon rains. Why aren’t the collapsing buildings repaired to save people who live in them? One answer seems to be lack of funds.

On 16 July, Bhanushali building in Fort collapsed, killing ten people. It was awaiting repairs since June 2019, when it was granted permission to be repaired from its own funds.

The Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation and Maharashtra Housing and Area Development Authority shift the residents out of the buildings, pull them down and erect new structures in their place. Some residents are wary of such a strategy as they fear being rendered homeless.

Not only does MHADA build houses but it is also responsible for the upkeep of these residential buildings. Many buildings commonly termed cessed buildings, pay a regular repair cess tax to the municipality. This tax is meant to be used for their upkeep.

However, MHADA claims the money is insufficient for the task at hand. “Many of the buildings are about 100 years old. It is costly and useless to undertake repairs of such old buildings as they are in a very bad shape and repairs are recurring in nature,” says Vinod Ghosalkar, chairman of the Mumbai Buildings Repair and Reconstruction Board (MBRRB) cell of MHADA.

This cell overlooks repairs and rehabilitation of cessed buildings and is now responsible even for their redevelopment.

The annual funding of MBRRB is currently Rs 100 crore (Rs 40 crore collected as repair cess, an equal amount contributed by Maharashtra State government, Rs 10 crore by the BMC and another Rs 10 contributed by MHADA).

It’s not just the age of the building that is a major deterrent for repairs but also years of neglect and disrepair that have rendered some buildings to be termed dangerous and beyond repair under the MHADA Act, 1976. Majority of ‘dangerous’ buildings are cessed buildings. But 56 BMC ones, 27 state government-owned and 360 private buildings are also classified as dilapidated. The BMC and state buildings are generally staff quarters, such as police quarters.

There are 14,207 cessed buildings located in Mumbai mainly in the island city. These include about 11,950 A-category buildings that were built pre-1940, about 963 buildings classified as B-category built between 1940-1950 and about 1294 buildings classified as C-category that were built between 1951-1969.

Till March 2018, of the total 14,207 cessed buildings in Mumbai, repairs were completed only for 688 buildings and they were being carried out for 1105 buildings.

Recommendations of an expert committee

An eight member committee submitted a report during the September Maharashtra Assembly session. The report acknowledged the lack of funds and recommended structural audits for the buildings every five years. It also suggested that a monthly premium be collected from the residents for structural maintenance. MHADA engineers should be mandated to inspect such buildings every three years, it said.

As per the 1976 MHADA Act, the housing authority would conduct repair of a building only upto Rs 3000 per sq meter. Beyond this limit, the owner or the residents are to pay for the repairs.

Amin Patel, a Congress MLA from Mumbadevi, was a part of the 8-member committee which submitted the report in September. He demanded that the ceiling limit be increased from Rs 3000 per sq meter to Rs 5000 per sq m.

He has also demanded that the annual funding for MHADA’s repair cell be increased from Rs 100 crore to Rs 200 crore, as had been promised in 2014 by the then Chief Minister Prithviraj Chavan.

According to information procured from RTIs, activist Anil Galgali found that MHADA had received Rs 560 crores as repair cess in the 12 years between 2007-08 to 2018-19. Yet this has proven to be insufficient.

By law, MHADA should provide alternative accommodation to residents during the period of repairs but its transit camps are already full and many of the transit camps itself have become dilapidated of late.

“Many times, the repair permissions become a guise to carry out illegal extensions by residents. These illegal works not just weaken the building further but also lead to corruption, since the contractor carrying out repairs collects money from both the MHADA and the residents,” says Amin Patel.

Many repaired buildings are strong for two decades or more, says housing activist and former President, MHADA, Chandrashekhar Prabhu. “Getting the repair permissions is not difficult at all. But, vested interests want the builders to push the residents of buildings into the redevelopment process rather than have them repaired,” he adds.

“There is a politician-builder- officials nexus. During my term as MHADA president, I had introduced the system of giving residents the option to carry out their own repairs with permissions and then have the amounts spent reimbursed by MHADA,” says Prabhu. That process seem stalled to a great extent now.