For the residents of Delhi’s many slums and jhuggi-jhopri clusters, Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal’s recent statement that the government is working on a drainage master plan must have sounded a cruel joke. Especially at a time when Delhi had just had its wettest September since 1944.

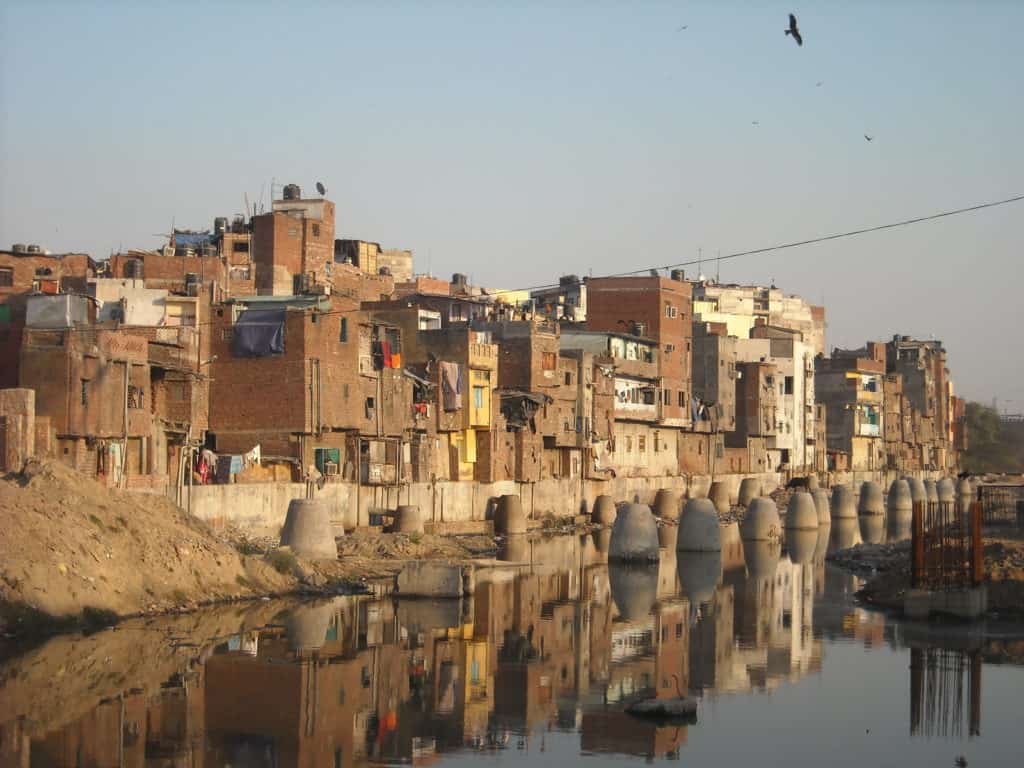

Till September 16th this year, Delhi witnessed 1159.4 mm of rainfall, the highest since 1964 and the third-highest ever, according to India Meteorological Department (IMD) data. Inevitably, the worst sufferers of this deluge were the 18.5% of the city’s population (estimated at 31,181,376 in the latest revision of the UN World Urbanization Prospects) living in these crowded jhuggi-jhopri colonies. They had to somehow cope with it all on their own, with no significant help from anyone in authority. The exceptionally heavy downpour with about seven heavy rain spells resulted in flooding, waterlogging from overflowing drains, water borne diseases and even longer power cuts than usual.

Delhi has an estimated 2,846 drains, covering a combined length of 3,692 KM. “The drainage system will be further bolstered and made foolproof,” Kejriwal promised. “Officers should conduct studies and find solutions for each and every storm drain and sewer system. Every gap in Delhi’s drainage system has to be plugged.”

What master plan?

Maybe even that will happen, in some unspecified future time. But for the present, the yearly monsoon flooding of the Minto bridge area in central Delhi has become a metaphor for the ineptitude of the various municipalities and boards that administer Delhi.

Particularly hard hit are those living in the slum clusters whose homes get swamped by sewage from the malfunctioning of much of this sewerage and drainage systems.

Read more: Delhi fights monsoon flooding with 44-year-old drainage plan

With the first Drainage Master Plan for Delhi being prepared in 1976, it took 42 years and severe flooding of major areas of the capital that led to the formulation of a 153-page second Drainage Master Plan for NCT of Delhi in 2018. But no steps appear to have been taken to implement this master plan.

Manoj Mishra who heads the Yamuna JiyeAbhiyan said that the 1976 Report itself had identified 201 natural drains that were flowing into the Yamuna and certain suggestions were made to repair them. But there was total disconnect between urban planning, the drains and the Yamuna. “The authorities never bothered about the nitty gritty of the natural drains,” said Manoj Mishra. “The city was allowed to grow without any plans with unauthorised colonies coming up in and around the natural drains, thereby clogging them.”

That this Master Plan remains a paper plan was seen during the recent rains when a slum cluster in Madanpur Khaddar’s Priyanka camp in South Delhi got flooded and people had to undergo immense suffering.

At one stage, what looked like a lake was the accumulation of waste water from hundreds of homes and from the public toilets provided for the residents. All the pipes connected through badly built and mismanaged sewerage drainage systems leaked onto the narrow alleyways, flowing into this huge cesspool. The camp has no garbage disposal facility either, which added to the problems.

Radha, a former domestic help living here with her children and grandkids opens the door to her two room home, to show the toilet which had been rendered useless, with waste water backing up and overflowing into the room when the rains were incessant. “The kids had to sit up on the bed, they couldn’t put their feet down,” said Radha. Now, the traces left behind are the clogged-up toilet, and next to it, in a dry spot, some dishes left to be washed.

Horror stories*

“No one does anything for us,” piped in a neighbour, joining the other residents who had stopped to talk even as they were jumping across puddles of sewage. “A few of us even went to the (AAP) MLA Amanatullah Khan and told him about this problem,” he said, getting angrier with each word. “We are always assured by the MLA and the MP (BJP’s Ramesh Bidhuri) that they will fix this, but they never do anything, they take us for fools”.

Rekha, another resident of the colony who lives in a one-room home like most others said that the one room served as their bedroom, kitchen, dining and living area. They have no toilet. The space is shared between her and husband, Premchand, and their 16-year-old daughter and 4-year-old son. Their daughter lies bedridden, never diagnosed but showing signs of neurological and developmental disorder.

“I can hardly keep the door open to let fresh air in because there isn’t any,” said Rekha.

Outside her home, the pool of sewage water, with people trying to avoid stepping into the muck, is a breeding ground for mosquito larvae while a little ahead there was a massive heap of garbage piled up in the corner.

“It’s horrible outside, then the flies and mosquitos come in,” Rekha adds. The health threat is two-fold for Rekha and her ilk, of vector borne and water borne disease – this was how she lost her second child, Swati, then her youngest, to typhoid in 2016.

According to data shared in the Lok Sabha in February, Delhi witnessed a total of 127 and 148 cases of Acute Diarrheal Diseases in 2018 and 2019 respectively. There were also 20 typhoid cases in 2018 and 2019, while Viral Hepatitis (A & E) saw 180 cases each in both years.

These tales of helplessness of residents is echoed in Ambedkar camp near Mangolpuri in North West Delhi and Yamuna Khadar near Laxmi Nagar in East Delhi. Waterlogged homes of waste pickers in Matiala, South West Delhi, on September 16th saw them plead desperately for help from the authorities as stacks of waste piled up at the entrance of their makeshift houses, built using tarpaulin, tin and wood. But their pleas went unheard.

Persistent problem with no solution in sight

The failings of poor drainage systems are not just felt by residents of the slum clusters. Every year much of Delhi faces urban flooding due to poor drainage. This despite having a ‘Drainage Master Plan for NCT of Delhi’, commissioned by the Congress government in 2012.

Read more: As Delhi works on Master Plan 2041, time to rethink city plans from the bottom up

“One problem is sewage entering into the storm water drains and this is largely due to rapid urbanisation and concretisation with no control,” said Sushmita Sengupta, Senior Programme Manager of Water Programme, Centre for Science and Environment. “Both problems are related: Unplanned construction chokes stormwater drains that carry rainwater, while rapid urbanization reduces groundwater recharge”.

Manoj Misra said one of the major problems in the capital’s drainage system is that there is no single authority to take care of all the drains. “No one is bothered over who should take responsibility for the drains,” said Mishra. “Each organisation passes the buck to others like PWD, DDA, DJB and this goes on till the next rainy season with the same recurring flood related problems. No single authority has accountability.”

58 drains vanish without a trace

Manoj also says that the National Green Tribunal (NGT) was hearing the case on Yamuna Rejuvenation, it was told by the Flood and Irrigation Department of the Delhi Government that 58 drains were found missing and could not be traced, said Mishra.

The former Indian Forest Service officer says one issue is the pollution caused by the use of polythene and improper disposal of plastic. “Then comes the manner in which civic authorities neglected the upkeep of traditional drainage lines,” said Misra. “At various places they have vanished, in some places they are built over and in others they have been covered. The solution is very simple. All obstructions we have created that prevents flood water reaching the drain has to be removed.”

A simple truth which everyone in authority in Delhi knows, but are unable or unwilling to do something about, Kejriwal’s good intentions notwithstanding.

*Acknowledgment: Information on the problems faced by residents of slum clusters reported here has been reprinted with edits with permission from Patriot. The original article can be read here.