This is the second story of a two-part series on why finding a sustainable solution to regulate Delhi’s legal and illegal street vendors is so difficult. You can read Part I here.

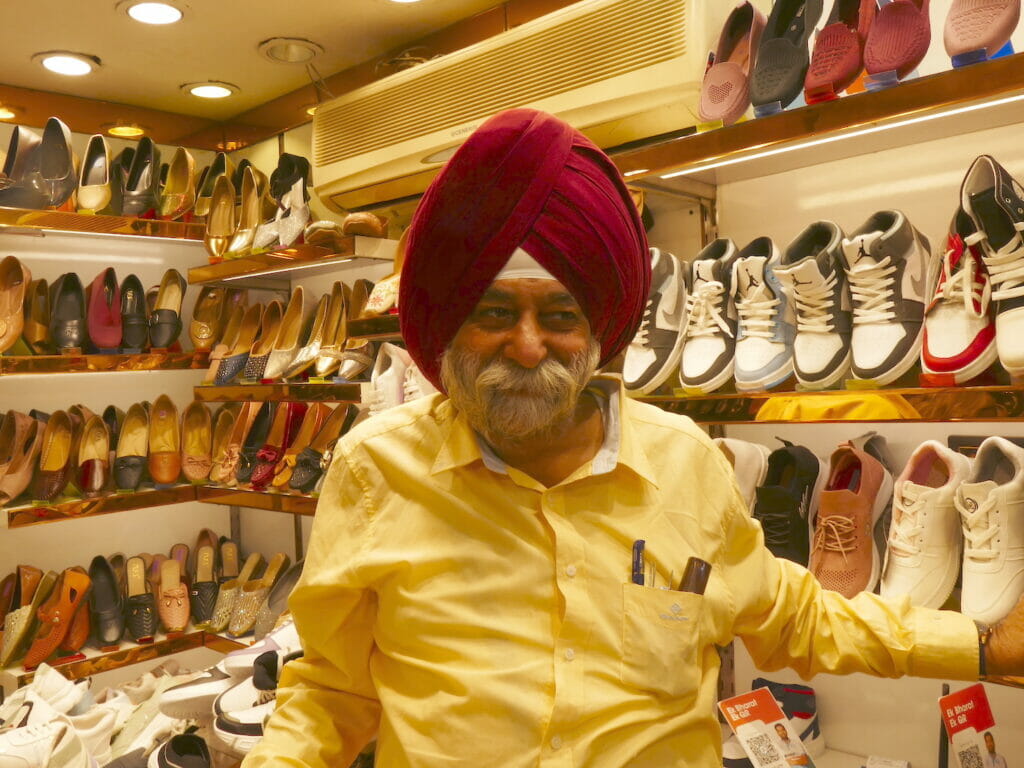

Kuldip Singh Sawhney, president of the Sarojini Market Shopkeepers’ Association, says they moved a case against the street vendors in the Delhi High Court in September 2021. “Our plea was that according to the Master Plan 2021, the vendors holding capacity of this market is 60 to 80. On an adhoc basis, 65 vegetable stalls were allowed and there are 125 Thareja vendors. In addition, 324 of the unauthorised ones got a stay in 2011 for two months, which is long over but they continue to be here. And then there are 2000 others,” he says.

A chat with Sarojini Nagar market shopkeepers introduces a few uncommon words to one’s vocabulary. Besides “Thareja vendors”, who have banners giving an address that reads “Opposite Shop Number 123” and “NDMC Authorised”, there are “mobile vendors”, who move around selling their wares, there are “sitting vendors”, and “body hawkers or body vendors”, who carry their wares on their bodies, none of whom have any ID cards. Between them all, little space is available for pedestrians or shoppers to walk.

Vishal Rekhi, who has given his property on rent to a store points out that street vendors pester visitors. “More seriously, they are a security threat,” he says, recalling a bomb blast in G-Avenue of this market in 2005, when 45 people were killed and over a 100 injured.

“If there is a fire incident or a security lapse, it is impossible to help people out,” he says. “The NDMC had earlier decided that the footpath on one side of the market would be a “no vendors zone”. The police and the NDMC staff are there, but today there are scores of vendors too”.

Read more: What are the demands of Mumbai’s street vendors?

Rekhi adds that the 100-odd families living on the first and second floor are scared. Even the high court said the vendor issue was a ticking time bomb, and warned them against leaving their material outside at night. But the vendors have ignored this.

On the AAP manifesto promise to find a solution, Kuldip Singh Sawhney says, “The government has to identify space outside the market, or think of having night markets like in Bangkok from 9pm to midnight or an early morning market from 6 to 8am to stagger the crowding and congestion”.

Shopkeepers are also angry that while they pay a rent of Rs 2-3 lakhs a month, the vendors ply their trade for free. “The vendors have no rent to pay, no GST, no electricity bill, and no staff. They should be given a vending zone outside Sarojini Nagar market”, says Sawhney, who suggests moving vendors near some of the 12-storey buildings coming up as part of the Sarojini Nagar redevelopment.

In fact, the NDMC did create the Lakshmi Bai Nagar Vending Zone to relocate many of them. But none moved, because there were no customers coming to Lakshmi Bai Nagar.

A livelihood issue for street vendors

Apparently, the business volume of the street vendors is sizeable. Most of those who sit on the same part of a pavement day after day, and have a bench or bundle to hold that spot, have stuff worth about Rs 25,000 at a time. Hawkers who move around carrying their wares have things worth Rs 10,000 to 12,000. It gives them livelihood, which they are not willing to risk by relocating to a new location.

No squatter outside Palika Bazar or Sarojini Nagar market has ever made enough to realise a dream some of them nurse— of owning a pucca shop inside the market.

“That can never happen,” says vendor Mahesh Kumar. “All the shopkeepers want us out, because their business gets affected”.

Though they may not pay rent and taxes, street vendors pay money to NDMC staff and the police. “It is not like we are here for free, and have no expenses. It is just that we don’t have receipts, we don’t have security or rights to our space,” adds another vendor.

Raj Kumar, who shows the NDMC card authorising him to squat, says that many squatters have died, but their legal heirs are not able to get the squatting rights transferred to them. “We are insecure even if we have permission to sit and sell in this 6×4 space,” he adds.

Read more: Bengaluru’s street vendors: A vibrant community deprived of rights

At the end of the day, it is about either owning or encroaching a public space to earn a livelihood. And about grabbing a share of footfalls in a market. The bottom line being livelihood, or the lack of it, for millions.

The vendor’s issue is also much about politics, with the Union Government owning the land and controlling the city police on the ground, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) having plenty of MPs and calling the shots in the capital city’s local bodies for 17 years now, and the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP)’s MLAs in most of these localities.

Caught in this political web, the affected parties have so far kept clear of taking up their issues with any of these political and government authorities, and preferred to knock at the doors of justice.

Now that AAP has won the MCD polls, it will be interesting to see how it proposes to solve the issue of street vendors vs traders. In the run up to the MCD elections, the party leadership had mainly been telling the traders, “We will clean the vending zones which will make the market look beautiful automatically.”

But in November 2021, they did talk about “working on a highly progressive policy for street vendors”without going into any details.

The outcome on the ground remains to be seen.

Very well written piece by Vijaya Pushkarna.Its interesting to learn nitty gritty problems that vendors are facing at alltime favourite shopping place for most of us!!