[This article was co-authored by Rakesh Kumar Sinha. Rakesh holds a PGDCA from CMC, Delhi and a Certificate in Computing from IGNOU. He has worked as a research assistant in Policy and Planning Research Unit of Indian Statistical Institute.]

On Sunday 08 December 2019, 43 people lost their lives in a tragic fire in a Delhi small-scale manufacturing hub. Most victims are young migrant labourers from states like Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. It was reported that factories were located illegally on residential premises, and an electrical short circuit possibly caused the fire. At least five of the 43 victims were minors, with some as young as 13, employing whom is a clear violation of existing labour laws in the country. Reportedly, authorities expect the numbers to rise.

Delhi’s revenue surplus over last five years is being celebrated across media. It was made possible with a very healthy increasing trend of the revenue receipts from Rs. 16352 Cr in 2008-09 to Rs. 47557 Cr in 2018-19 (BE), with a trend growth rate of over 10%. However, the Delhi fire tragedy and the presence of child labourers among victims force one to ask the question: how much of Delhi’s economic sheen is being underwritten by minors and child labourers working in ‘Dickensian conditions’?

Please note here that the government does not consider all working minors as child labourers – only those under 14 years of age come under this category.

Studies focusing on child labourers in Delhi have found that they live and work in poor conditions in terms of exposure to risks and hazards like loud noise, poor lighting, poor ventilation and sharp tools. Reports on the working conditions of the Delhi fire victims sound eerily similar. They found that the illegal factory was packed with combustible material, had just one door, and workers were sleeping on the same floor where sewing machines, plastic toys and boxes, rexine rolls, plastic wrappers, cardboards, packaging material and garments were kept. There is an accident like this waiting to happen at many other locations across Delhi.

Till this year, the latest data set that could give an estimate of child labourers in Indian states was the Employment-Unemployment Survey (EUS) 2011-12 of the National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO). Based on analysis of the unit level data from this survey, a study by the Observer Research Foundation (ORF) titled “Retired at Eighteen: Political Economy of Child Labour in the Textiles and Allied Industries in India“ estimated the number of child labourers in Delhi under 14 years of age to be 2,358, almost all of them Dalits.

However, with data from the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) 2017-18 released earlier this year, we have a more recent dataset giving us a robust estimate of child labour at the state level. Experts caution that EUS and PLFS are not strictly comparable as sampling weights used in these surveys are different. The PLFS gives a larger weight to households with more educated members aged 15 or above, and it can inflate the unemployment estimates, it is argued.

However, in the case of child labour, this new methodology focusing on a more educated sample would lead to an estimate which is far rosier than the actual situation, if anything. With this caveat in mind, a look at the Delhi numbers still proves to be very revealing.

Initial analysis shows that in the year 2017-18, the number of child labourers by legal definition – those under 14 years of age – in Delhi was 32,330. The degree of increase over half a decade from 2,358 to 32,330 is nothing less than shocking.

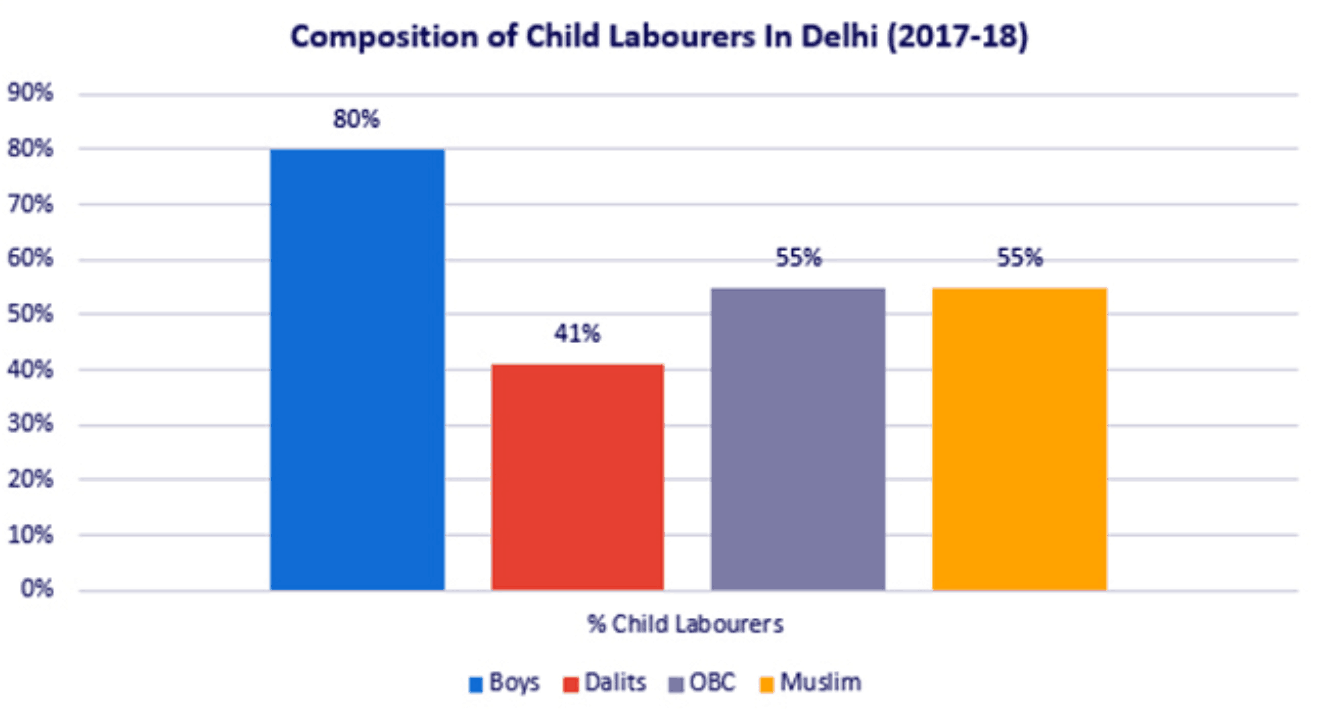

More than 80% of these children were boys, and 55% of them were from the Muslim community. The proportion of Dalits among child labourers, which was 100% in 2011-12 has come down to 41% in 2016-17. Now, 55% of the child labourers are from Other Backward Categories (OBC) communities – in this case, exclusively Muslim. Under 3% of child labourers in Delhi come from general castes.

Source: Unit Level Data from Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) 2017-18

This dramatic increase has happened during a time the overall number of child labourers in India has shown a remarkable decline, from almost 2.7 million in 2011-12 to just under 1.3 million in 2017-18. The Aam Aadmi Party’s highly celebrated work on truly universalizing quality school education, somehow, failed to bring down the number of child labourers in Delhi.

What compounds India’s child labour problem is that a large part of it is considered ‘legal’, according to the ORF study. The current definition of child labour leaves children between 14 to 18 years old in a limbo – they are considered too young to be adults but old enough to be out of school and in low-paying, low-productivity jobs. These children will remain underemployed and unemployed in their adult life, when they are eventually replaced by younger, cheaper hands; by then, they would not have nurtured any skills to move to other gainful employment. A vicious cycle is perpetuated, whereby fragmented welfare schemes subsidise them for the rest of their lives.

As one of the youngest nations in the world with two-thirds of its population below 35, India still has time to reap its demographic dividend. The expansion of the Right to Education Act to include compulsory and quality secondary education as suggested in the National Education Policy 2019 draft will, hopefully by implication, result in a revision of the definition of child labour and enhanced action. Till that time, governments like Delhi with their expressed commitment to social sector investments should show the way by eliminating child labour from the economy. This avoidable tragedy at the Anaj Mandi should possibly shake the Delhi administration out of its slumber.

The story was first published by Observer Research Foundation (ORF) and has been republished with permission. The original article can be found here.