Besides health, the socio-economic distress caused by the pandemic is likely to leave a deep impact on the urban milieu. Urban agglomerations are often characterized as organic, dynamic life systems quite capable of being able to adapt, respond to opportunities and absorb adversity. Their vibrancy is argued to be inhibited and even distorted by state interventions. The disparities and inequalities that characterize several Indian cities might lead one to question these beliefs even during regular times. However, the pandemic has thrown up several new questions on the resilience of cities. Whether this be the exodus of migrant workers, loss of urban jobs, reports of suicides caused by economic distress or the baring of the grossly inadequate health infrastructure.

The few positives that have emerged, have emerged from the response of local actors who have taken it on themselves to respond to the emergency around them and repeatedly exhibited their initiative and capabilities. This has included both civil society action as well as that of exceptional city administrators who set examples like the “Mumbai model”. The common element being decentralized, civic-minded public action.

Read more: Did Mumbai turn the tide on COVID19 thanks to its deep coffers?

Can the learnings from the emergency response in the domain of health and medicine be extended to the socio-economic as well?

Local actors have, in particular, highlighted the merits of decentralization. How will centralized actors respond, so that we move towards more sustainable and resilient cities? What kind of state interventions will work with market forces to create more equitable outcomes?

Answers to these questions are important across arenas. But the important and immediate one is the question of urban jobs.

Read more: Urban employment guarantee Part 1: “Desperate times call for desperate measures”

Earning with dignity

Work or employment, as has been pointed out frequently, is not just about earning money. It is also about dignity. A frequent refrain we often heard while distributing food to those who had lost their jobs during the lockdown was “koi kaam ho to batayeiga..hum kaam karne wale log hain” (“please let us know if there is any work…we are people who work).

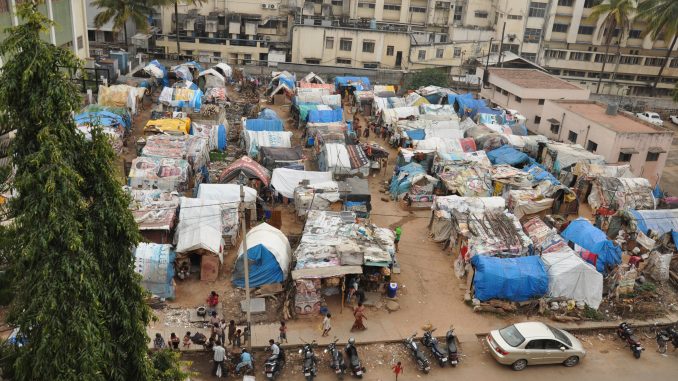

A proposal whose importance has now been reinforced, as cities come out of lockdowns, is a nationwide programme that would guarantee urban jobs for the poor. Such programmes have been resisted because of the fear of attracting increased migration to already crowded cities.

While on the face of it, this might appear to be true, such characterizations ignore two critical elements. Migration is more often distress or push-based, reflecting the abysmal conditions in the migrants’ villages. The way to address that is to improve conditions in rural India and not depress those in urban areas.

Secondly such a view ignores the fact that the so called ‘migrants’ are really the ones who make any city function. The question should really be how does one create fairer, socially just outcomes that also accomodates the dynamism of market forces.

Prof Jean Dreze’s framework for a ‘Decentralised Urban Employment and Training’ (DUET) program is one that offers a practical possibility to respond to these paradoxical demands. It builds on other proposals from Prof Amit Basole and others.

Read more: Urban employment guarantee Part 2: The challenge lies in making it viable

While Kerala’s Ayyankali Urban Employment Guarantee Scheme and Tripura’s Urban Employment Programme were interventions predating the pandemic, others like Odisha, Himachal Pradesh, and Jharkhand have done so in response to the pandemic induced distress.

However, as Basole & Swamy (2020) point out, most state-level schemes have limited budgetary allocations despite being labelled “job guarantee” schemes.

Woman-focussed

As proposed, DUET does not offer an employment guarantee but is proposed as a nationwide, demand driven and self-targeting scheme with no eligibility restrictions. Further, unlike MGNREGA which has a quota for women workers, Dreze suggests that DUET primarily be focussed on providing employment to women (“as long as women workers are available, they get all the work”) .

Read more: COVID-19: Women, children in low-income housing bore the worst brunt

Unlike MNREGA, in which the primary onus of organising jobs falls on the government, the DUET envisages the government’s primary role to be issuing of “job stamps” and the creation of a ‘placement agency’. The placement agency’s task is to register potential workers and guide them to work. The job stamps are proposed to be distributed to approved institutions — initially public and subsequently private, non-profit — who then use them to provide jobs and pay workers.

Enhancing the priority to women, Dreze suggests these placement agencies be run or managed by women (or collectives of women). There are further details that Dreze and others have suggested in several discussions, while others can be worked out in due time.

However, the critical element is an increased role for the state in providing social protection via employment in urban areas. In this sense it also distinguishes itself from other forms of support like the Public Distribution System.

For DUET to gain traction, it is essential that towns and cities take the initiative and set the ground for a nationwide programme to ensure urban jobs. One set of key actors that need to be called for this task are Ward Councillors. As local elected representatives, they are embedded in the community and informed about both demand and supply opportunities.

Ward councillor, the key player

Many of the larger municipal corporations also have discretionary funds allocated to ward councillors (for example, councillors in Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation get around Rs 30 lakh every year). Combining this with local area development funds of the local MP and MLA, councillors could run pilots without necessarily waiting for support from the top. If they are able to garner cooperation of the executive, city budgets could also be attracted to creating employment while simultaneously meeting more pressing needs of a city like maintenance of existing public infrastructure like schools and anganwadi centers.

A councillor driven urban jobs initiative, that might be supported by civil society organisations, would help generate alternate models for experimentation. Learnings from them can be used to subsequently scale up. Given that the accountability platform of elections already exists for councillors, they should not be mired by requirements of bureaucratic accountability that would curb experimentation.

The important requirement would be to ensure transparency through mechanisms such as public sharing of work availability, muster rolls and payments for materials. What must be avoided is the creation of new parastatal organisations that create regulatory ambiguity and further undermine democratic accountability.

If our towns and cities are to provide a better quality of life to its residents, more formal engagement with elected representatives should not be considered a matter of choice, but a necessity. And building an urban employment programme with their active involvement should be an integral part of any programme design.