It has become a norm now. We go all out for festivals. We need to fulfil our desires to celebrate and conform to practices laid down by ancestors or traditions that simply happened over time. And then, in hindsight, we take stock of everything – the money we spent, the bills we ran, junk we ate and the waste and pollution that we contributed to. We promise ourselves every year to do better next time. Until the cycle repeats over and over.

This Diwali was no different. Not to mention the World Cup fever that only added to the feelings of collective frenzy.

The news of increasing pollution and a proportionate rise in respiratory disorders has become a daily occurrence that we gloss over. But several smoggy days before the festival had prompted the authorities to plan measures. Citizens have already filed a public interest litigation urging the court to intervene in the city’s pollution management. There were some campaigns about green crackers, though personally I am less convinced by that entire experiment.

The Bombay High Court had stepped in and issued an order specifying a two-hour-window – from 8 pm to 10 pm – when people could burst crackers.

Pollution related to Diwali becomes a topic of much discussion and contention, where one argues about temporary discomfort (which is actually not so temporary) for short-lived joy of bursting crackers.

Worrying numbers

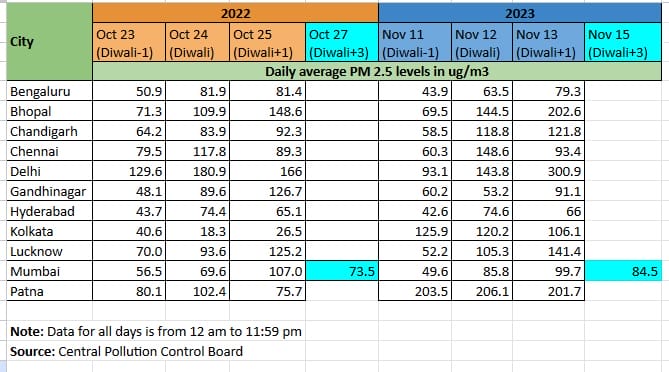

NCAP Trackers, a joint project of Climate Trends and Respirer Living Sciences, have put two kinds of figures – average pollution figures that mapped pollution during Diwali days in 2022 and 2023 in 11 cities, including Mumbai. The other figures are of spikes in pollution in different pockets of the 11 cities.

If one looks at the average pollution levels – PM 2.5 – on the four days of Diwali, it shows that there wasn’t much difference in 2022 or 2023. The levels ranged between 70 to 100 – from moderate to poor.

Fortunately, for Mumbai and the burdened lungs of its people, it had rained, out of the blue, which settled a lot of construction dust and reduced AQI levels before Diwali.

However, instead of preserving that drop in AQI levels, citizens defied the High Court orders by bursting crackers well past 10 pm in several areas of the city. The data of spikes in pollution levels by NCAP Trackers, shows the AQI peaking to 800, which is beyond very poor and highly risky, in various areas such as Chembur and Kherwadi in Mumbai.

The time for these spikes is well past mid night in all the cities, clearly showing little regard for the legal restrictions or fellow neighbours and neighbourhoods.

Read more: Opinion: This Diwali, let’s just be selfish!

Light and sound pollution

Sheetal Purandare, a Shivaji Park resident, and a mother of two children, pointed to another kind of pollution – light pollution. She spoke about “unbelievable amount of lighting” everywhere around the park and huge crowds assembling to take selfies under the artificial twinkling, glittering and shining canopies. This also resulted in traffic and vehicular pollution even as people continued bursting crackers. The lighting will continue till November 27th, the last day of Tulsi Vivah.

Reports about noise pollution from Awaaz Foundation suggested increased decibel levels during the two hour window and even later in a few places, where the orders were not followed. The reports also indicated that the air pollution levels would be poor for a longer time due to the chemicals in the crackers. Perhaps the only positive takeaway was reduction in the number of aerial crackers.

Are we really serious?

We continue to talk about the impact of crackers on animals, children, and older people. Issues about working conditions in the factories that make crackers have been discussed for years. There are innumerable studies about the chemicals that linger in the atmosphere and its impact on our health.

I worry that by the time policymakers, citizens and authorities arrive on the same page of putting collective health of people and the city as a priority, it might be a classic case of too little too late. Till then we will have to count on unseasonal showers to see us through.