Nearly three years after the Coastal Regulation Zone (CRZ) Notification, 2019, the State Environment Department published the draft Coastal Zone Management Plan (CZMP) and land use maps for Chennai and other districts in October 2022.

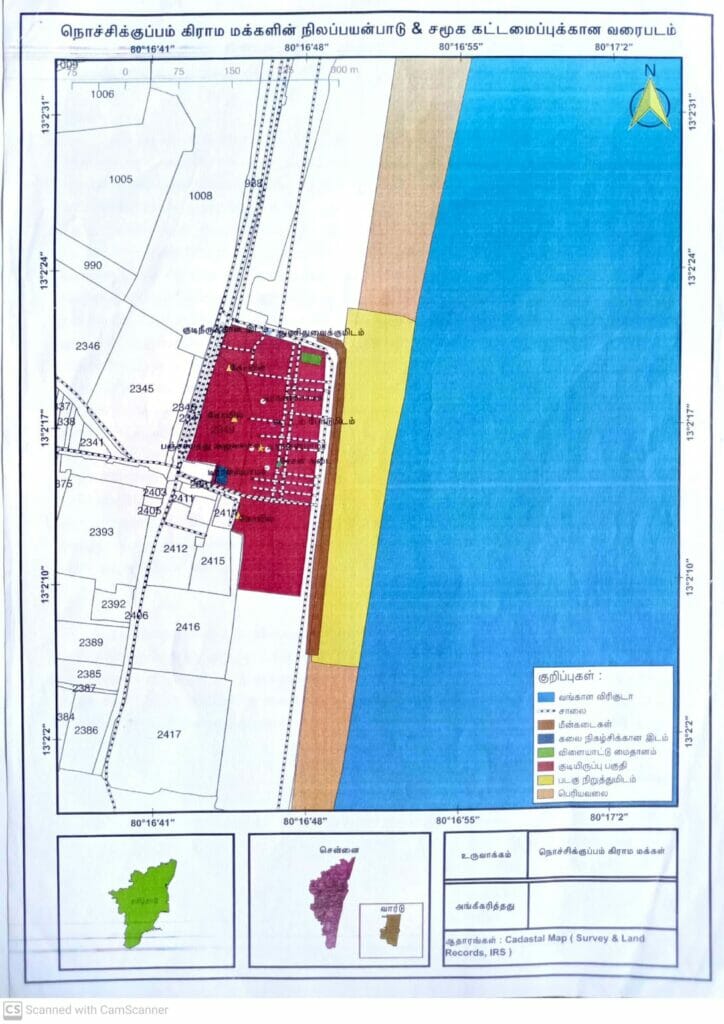

The National Centre for Sustainable Coastal Management (NCSCM) prepared the base maps that have the demarcation of eco-sensitive areas (ESAs) like mangroves, coral reefs, sand dunes, mudflats and turtle nesting grounds and other coastal infrastructure in different colour codes.

However, the fishing communities in Chennai have registered some strong objections to the draft Coastal Zone Management Plan as they have found many mistakes in the plan that could potentially affect their livelihood and the larger coastal environment.

Read more: Why fisherfolk in Chennai are opposed to beach beautification projects

What is Coastal Zone Management Plan?

The Central government issues the Coastal Regulation Zone (CRZ) Notifications under Environment (Protection) Act, 1986 to protect the coastal environment and to regulate development activities along the coastal areas. The aim is to ensure livelihood security for the fishing communities and other local communities living in the coastal areas, to conserve and protect the coastal stretches, and to promote sustainable development in the coastal areas.

In order to implement the CRZ notifications, a Coastal Zone Management Plan (CZMP) and land use maps have to be prepared.

According to CRZ Notification 2019, the Coastal Regulations Zones are classified as follows:

CRZ-I: Areas are environmentally most critical and are further classified as CRZ-I A and CRZ-I B

CRZ-I A: ecologically sensitive areas (ESAs) and the geomorphological features which play a role in maintaining the integrity of the coast

CRZ-I B: The intertidal zone i.e. the area between the Low Tide Line (LTL) and High Tide Line (HTL)

CRZ-II: developed land areas up to or close to the shoreline, within the existing municipal limits or in other existing legally designated urban areas, which are substantially built-up with a ratio of built-up plots to that of total plots being more than 50 per cent and have been provided with drainage and approach roads and other infrastructural facilities, such as water supply, sewerage mains, etc

CRZ-III: Land areas that are relatively undisturbed (viz. rural areas, etc.) and those which do not

fall under CRZ-II. It is further classified into CRZ-III A and CRZ-III B.

CRZ-III A: Such densely populated CRZ-III areas, where the population density is more than 2,161 per square kilometre as per the 2011 census base, shall be designated as CRZ–III A and in CRZ-III A, area up to 50 meters from the HTL on the landward side shall be earmarked as the ‘No Development Zone (NDZ)’, provided the CZMP as per this notification, framed with the due consultative process, have been approved, failing which, an NDZ of 200 meters shall continue to apply.

CRZ-III B: All other CRZ-III areas with a population density of less than 2,161 per square kilometre, as per the 2011 census base, shall be designated as CRZ-III B and in CRZ-III B, the area up to 200 meters from the HTL on the landward side shall be earmarked as the ‘No Development Zone (NDZ)’.

CRZ-IV: water area and shall be further classified as CRZ- IVA

CRZ- IV A: The water area and the sea bed area between the Low Tide Line up to twelve nautical miles on the seaward side

CRZ-IV B: areas shall include the water area and the bed area between LTL at the bank of the tidally influenced water body to the LTL on the opposite side of the bank, extending from the mouth of the water body at the sea up to the influence of the tide, i.e., the salinity of five parts per thousand (ppt) during the driest season of the year.

Read more: Coastal zone management plan does not follow rulebook; communities feel betrayed

Coastal Zone Management Plan and the coastal environment of Chennai

For a coastal city like Chennai, the Coastal Zone Management Plan is not only important to safeguard the livelihood of the fishing communities but also the coastal environment which has a huge impact on all our lives.

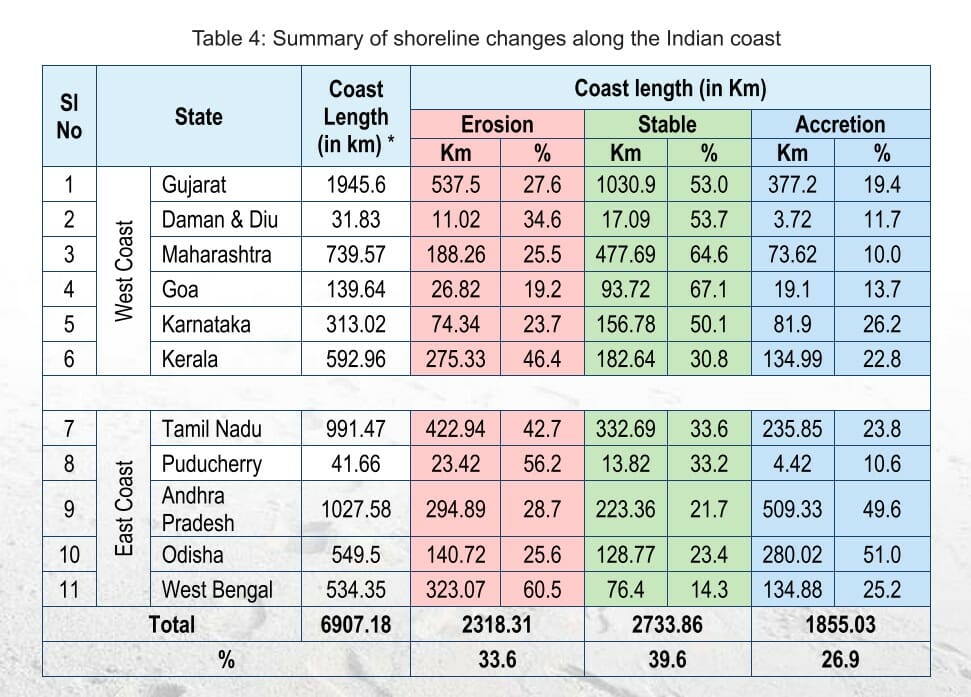

According to the National Assessment of Shoreline Changes along the Indian Coast conducted by the National Centre for Coastal Research (NCCR), 42.7% of Tamil Nadu’s shorelines are eroding. Compared to the shoreline changes study of 1990-2016, Tamil Nadu has been showing increasing trends of shoreline erosion and accretion, the assessment points out.

The draft Chennai Climate Action Plan released by the Greater Chennai Corporation also highlights that 100m of the coast is at risk of submersion as a result of 7 cm of sea level rise in the next 5 years. It also points out that the slum-dwellers would be at risk of sea level rise.

Impact of sea-level rise in Chennai according to draft Chennai Climate Action Plan:

- 16% of the GCC area (67 sq.km.) is to permanently inundate in the 2100s which will affect the 10,00,000 population of the city.

- 17% of the total slums (215 slums) residing (approximately 2.6 lakhs population) is expected to get affected

- Higher risks in high-density slums located around creeks and rivers

- 7500 TNSCB tenements built for the resettlement of slums are also to be affected

- North Chennai Thermal Power Plants is going to be impacted as well, which will require replacement by 2050.

Given the environmental implications of sea level rise, it is pertinent to have a Coastal Zone Management Plan for Chennai that is bulletproof.

Coastal Zonal Management Plan significant for Chennai fisherfolk

K Bharathi, President of the South Indian Fishermen’s Welfare Association, points out that the Coastal Regulation Zone (CRZ) Notification, by definition, is aimed to ensure livelihood security for the fishing communities.

“The Coastal Zone Management Plans are the base plan with which the notification is implemented on the ground. If this is not done properly at the draft stage, it will neither save our livelihood nor save the coastal environment,” he says.

This CZMP becomes particularly crucial at a time when the government is announcing a range of new projects along the shoreline and even inside the ocean.

Bharathi says, “The first CRZ notification was released in 1991 for which the Coastal Zone Management Plan and the maps were approved in 1996. Despite publishing the new CRZ notification in 2011, the government continued to use the 1996 plan till 2018. At the end of 2018, they hurriedly approved the CRZ Notification, 2019.”

After nearly three years, the draft plan and land use maps have now been published. Bharathi points out why the plan is crucial for the fisherfolk of Chennai. “We have been living on the shores and depending on the sea for our livelihood for generations but many fisherfolk have not been given a patta in Tamil Nadu so far. Coastal Zone Management Plan is the only way to ensure our basic rights are upheld. So it is very important to us.”

Issues raised by Chennai’s fisherfolk

Bharathi points out that the draft Coastal Zone Management Plan, which should be aimed at protecting the livelihood of fisherfolk, who are the primary stakeholders, and the coastal environment, has done the opposite.

“The plan should have a clear demarcation of our residential areas. This is important because the people from the fishing community have the right to stay at a given distance from the sea. The existing residential areas of these fisherfolk are not marked clearly in the draft Coastal Zone Management Plan and the land use map,” says Bharathi.

This move makes the fisherfolk, who have built their houses in areas outside the demarcated boundaries, seem like violators. “However, technically, these houses have been here for generations and all of us would become violators just because the boundaries are marked wrong,” says Bharathi, adding that the draft Coastal Zone Management Plan has also left out many fishing villages altogether in Chennai and other districts of Tamil Nadu.

K Saravanan and his team from the Coastal Resource Center, helped the fishing communities in Chennai and other districts to map their villages using World Geodetic System 1984 (WGS84) method (an international standard used in cartography, geodesy and satellite navigation including GPS.) More than 100 fishing villages have sent detailed land-use maps identifying their use of coastal and ocean/riverine commons to assist the State in preparing the maps.

“These maps not only have the correct boundaries of the residential areas but have also included the boat landing points, the places where we keep our fishing nets, the fish markets like the one on the Loop Road and other fishing-related activities that takes place in the locality. Despite sending these maps to the government, none of it has been included in the draft Coastal Zone Management Plan for Chennai,” notes Bharathi.

“We have been fishing here for generations and only we know the use of certain spaces here. Unless the government discusses it with us, they will never know about it. They have failed to mark the functional fish market in Loop Road, how will they ensure our livelihoods are secured?” asks Murugan, a fisherman.

These gaps in knowledge can be plugged with proper representation. There should be three representatives from the fishing community in the District Coastal Zone Management Authority as per norms but none of the districts in Tamil Nadu, including Chennai, so far has appointed the representatives.

“Similarly, the ‘no-fishing’ zone from the ports was marked only at a distance of 500 meters earlier but now the boundaries of the no-fishing zone have been extended to 7 km from Chennai Port, 17 km from the Ennore Port and 17 km from Kamarajar Port. There are over 25 fishing villages in Chennai who will not be able to fish anywhere in the sea if these boundaries are approved,” notes Bharathi.

Further, according to the draft plan, the boundaries of High Tide Lines (HTL) have been closed near Pattinapakkam in the Adyar River, while it should have been extended further.

“We do not understand how the HTL boundaries have been determined. Besides, there is a huge porting of mangroves near the banks of the Adyar river for which a buffer of 50 meters should be marked. The existence of mangroves also makes this zone fall under CRZ-I A where no construction is allowed. However, the draft has shown the portion as ‘outside CRZ zone,’ which means those who have built the building structures there are let off the hook,” explains Bharathi, adding that reducing the limits of HTL, would only give way for the outsiders to stake claims on the lands of the fishing communities and carry out any project in the guise of development.

Inaccessible documents due to absence of Tamil translation

Another grievance of the fisherfolk has been that the draft Coastal Zone Management Plan has not been made accessible to all with a Tamil version being made available to the public.

K Saravanan, a fishers’ rights activist from Urur Kuppam, filed a plea at the Madras High Court seeking a full translation of the draft Coastal Zone Management Plan in Tamil

Advocate General R Shanmugasundaram, who made an oral submission before the Madras HC during the plea hearing, said that it will be difficult for the state environment department to translate all documents of the draft Coastal Zone Management Plan prepared by the Centre’s NCSCM and only the legends in the maps can be made available in Tamil.

“The court has ordered the government to publish the Tamil translation. Once the government publishes the draft in Tamil, 45 days should be given for the people to respond with their objections and then a public hearing should be conducted,” notes Saravanan.

Officials from the District Coastal Zone Management Authority maintain that the plan was still at the draft stage and the suggestions from the fisherfolk would be taken into account before it is finalised.

While the fisherfolk have made a strong case for why the draft plan is flawed, they await a Tamil translation to further parse the plan and point out their objections at the public hearings. With their future and Chennai’s coastline at stake, they hope that they will get a fair hearing from the authorities on this crucial issue.