Our roads are not designed for driving below 50 km/hr, so why should one be penalized for pushing on the accelerator? For starters, I am a relatively slow driver. This subjective disclaimer is no proof before the Rs 1000 fine I was charged for going over the speed limit in Chennai recently.

Following this, I started driving consciously and analyzing speed behaviours in different parts of my daily commute, only to realize that speed is inherently connected to the roads you are driving in.

Fundamental issues with road design

Roads in India, at best, are planned for a comfortable journey during peak hours. Ironically though, we are all always stuck in traffic. Our road planning guide, the Indian Road Congress (IRC), uses peak hour counts and projections to justify the number of lanes required on a street.

In Tamil Nadu, we witness a steady 10% growth in private vehicle ownership, incrementally, causing our streets to choke sooner than milk overflowing at high heat. Our street edges are left without definition. Pedestrian pathways are kept at a minimum, with varying shoulder widths based on the adjacent land uses – thereby leaving us with irregular carriageways, disorganized lane markings, and discordance in lane continuity.

Read more: How can Chennai improve pedestrian safety?

Embracing congestion on city roads

A direct by-product of this unsystematic, location-based Right of Ways (RoWs) (as opposed to network-based RoWs), and the lack of efficient and reliable public transportation, is congestion. The straightforward solution to tackling congestion begins with finding strategies to reduce the number of vehicles on the road.

However, our city engineers only find this as an opportunity to arbitrarily widen roads where possible and build more flyovers, inducing demand. From an economist’s standpoint, increasing the supply of something (like roads) makes people want that thing even more, with little to no change in the intensity of road traffic. In contrast, building cities and keeping people and their lived experiences in focus will bring in more people and attracting more people will improve the local economy and, in turn, benefit the city.

While we make the bold attempt to build cities for its people, we must start getting comfortable with congestion. Congestion is a significant deterrent to opting for private vehicles.

Our tried-and-failed solutions of increasing road widths and building flyovers, on the other hand, instigate fast driving behaviours. When decades of our policies and planning methodologies support such rash driving, why penalize only me (and other road users) for speeding?

Limiting speeds and apportioning blame

Indian cities are deteriorating at a rampant speed. They are increasingly unsafe for children to access streets independently, elders to cross without supervision, adults to merely walk, and the physically challenged to even exist.

A speed limit like the one that sparked a recent debate in Chennai, if adhered to, is the band-aid solution. To get to the bottom of it, redesigning our roads and providing a compact intersection geometry that prioritizes pedestrians is critical.

Geometry and vehicular speeds on roads

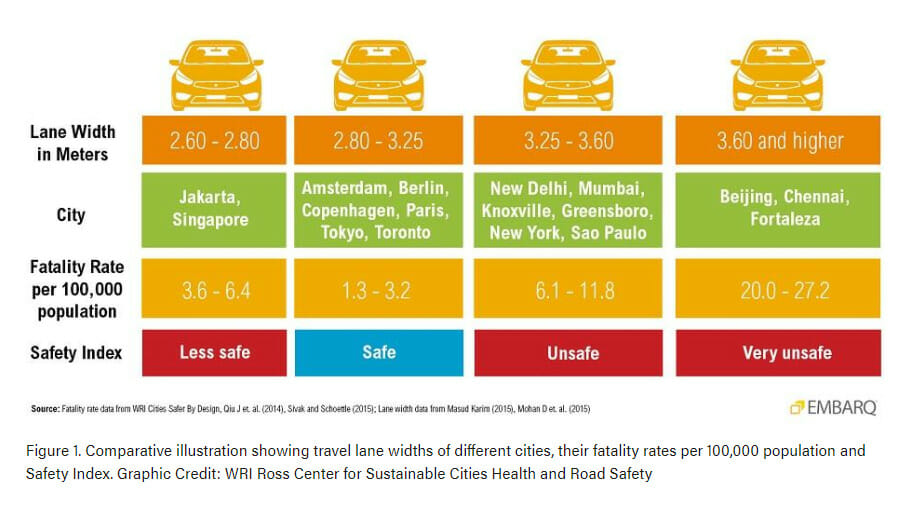

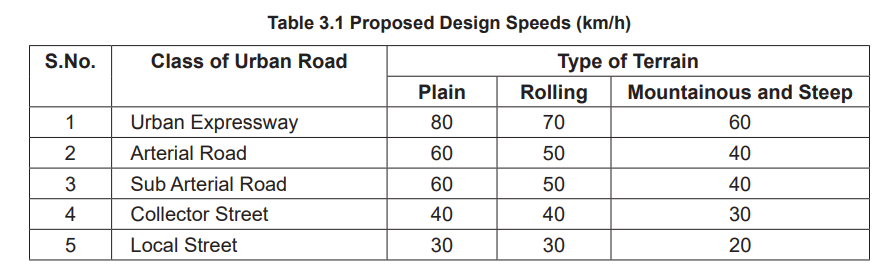

For all things concerning roads and road networks, the IRC specifies a minimum value. Based on the topography, type, and location, the IRC details the minimum carriageway width, lane width, turning radii, and sight distance values, amongst other pertinent information. These minimum values determine a design speed. Design speed is the target speed at which drivers are intended to travel on a street. And not, as often misused, the maximum operating speed.

Our private vehicles pose the most apparent threat to congestion, and consequently, pedestrians occupy a blind spot in the design. Pedestrians, on most streets, are restricted to the edges – sharing space with motorists, parked vehicles, utility boxes, vendors, and garbage bins. In places where they are mandated to provide a sidewalk platform, a meagre 1.0m-1.5m is offered out of pity, despite their actual volume.

Private vehicles, on the other hand, are treated liberally, with varying lane widths beyond the minimum, wide shoulders, large turning radii, and comfortable parking spots where possible. This generosity to private vehicle owners translates into an increase in the design speed of vehicles, thereby increasing operating speeds, even when not intended to.

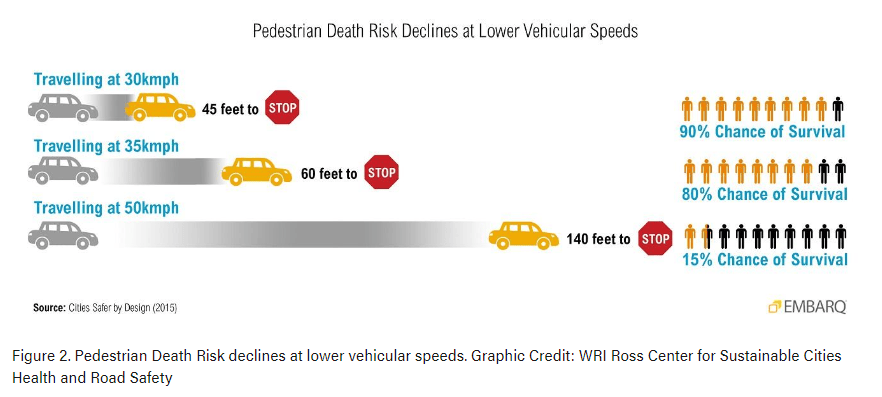

The Global Street Design Guide states that, every 1 km/h of increase in speed results in a 4-5% increase in the risk of death in case of a crash. Additionally, as a driver’s speed increases, peripheral vision narrows severely, impacting stopping distance and the risk of pedestrian fatality. Therefore, a speed limit is mandatory to minimize road fatalities.

Read more: Can imposing speed limits on Chennai roads make them safer?

What can Chennai do to fix its roads?

If Chennai cares enough about lowering vehicular speeds, they must avoid designing streets that enable cruising higher than the posted limit. Our junctions should be compact and our network streamlined. We must choose a narrow turning radius and use speed management strategies.

We must install physical barriers and grade differences between vehicles and vulnerable users like pedestrians and cyclists when speeds exceeding 40 km/h are permitted and fundamentally provide frequent opportunities for safe crossing, ideally between 80m and 100m, but no farther than 200m.

Roads designed for higher speeds will foster dangerous environments for all concerned. While the posted speed limit is a deterrent, it will only cause more violations and fines. The inherent fault of higher vehicular speeds is not entirely that of the end user.

We must rethink how our streets are planned, who gets priority, and who our streets are for. Until then, let us share this Rs 1000 penalty.

THE ABOVE ARTICLE IS 100% CORRECT. BUT IF IT IS LAID WITH QUALITY IT IS GOOD. THE QUALITY IS ENTIRELY WORST.

There are no designated parking areas, with the result vehicles are parked on the road. Traders are allowed to occupy the pavements liberally. There is not a single 100 meter stretch barring beach roads where one can walk on platform easily. The concept of stop signs and who gets priority, which are vigorously enforced in other countries is not at all there. The police is one who wears a uniform and does not take any action