Going over the stories I had worked on over the past year has been a bittersweet experience. While I was happy to be able to write on important issues, the pain of the people I encountered over the course of writing these stories is one I will carry with me for a long time to come. The thing about large cities like Chennai is how many people’s struggles are invisibilised, and their lives relegated to the margins.

Some of the stories that I penned endeavoured to spotlight the people who have fallen through the cracks in the system. Here is some of what I saw and what I learnt.

Temporary workers keep Chennai going at a great personal cost

It was in April this year that I moved to Chennai for my new job at Citizen Matters. In the first week of May, I saw the news about the protest of temporary workers of Chennai Metropolitan Water Supply & Sewerage Board (CMWSSB). The reason for the protest was the decision to outsource manpower through private contractors and overlook the demands of temporary workers engaged by the CMWSSB. Their demand was simple – to make their employment permanent.

When I went to the site of the protest on its 5th day, I saw hundreds of workers gathered for a sit-in. They organised themselves in a way that their protest would not affect the public. While a few workers continue to perform essential functions, the others were at the protest site.

At night, all the workers gathered and remained at the gate of CMWSSB despite the night-long rains. I was curious if the public was even aware of this protest because I clearly saw the workers cared for the welfare of the public.

When I asked a few of them what they would do if there is a heavy downpour or floods the very next day, they said without any hesitation that they would get back to work. “We have been doing this work for more than a decade. We know that the public will need us and we do not want to trouble them. Our fight is with the government,” they said.

Read more: Frontline workers in Chennai battle the rains with poor support and scarce empathy

In the meantime, when the workers were battling for their livelihood, the CMWSSB officials deployed daily wage workers to carry out routine tasks and also allegedly threatened the protesting workers with termination if they fail to report to duty.

Pointing out the irony in such a step, a worker asked, “Once we are back to work, they will terminate those daily wage workers. Who will support those workers’ families then?”

The protests came to an end on the tenth day without a positive outcome for the workers. They were forced to return to work under a temporary contract due to the possibility of losing their jobs.

From what I observed, the workers showed a deep commitment to the city and its people. However, they have been failed by the public who have been silent spectators. There were no voices of solidarity that could help invigorate their protest.

The same workers will have toiled after the recent Cyclone Mandous to restore normalcy, but do not receive any recognition for their work or support for their legitimate demands.

Where residents continue their 20-year wait for a proper home in Chennai

The second story I want to talk about is one of many failed promises.

The concept of ‘home’, a place where you can feel a sense of belonging, has always been intriguing to me. It is with this curiosity that I began looking into the various aspects of forced eviction in Chennai. In September this year, I wrote about the story of Kannappar Thidal and its residents.

Less than a kilometre from Chennai’s bustling Central Railway Station and the Ripon Building, is the world-class Jawaharlal Nehru Stadium, an important landmark of Chennai. Close to the Indoor Stadium Campus is a commercial complex which has an alley on its side, that leads us into a very different reality from these imposing structures. A dilapidated building that is home to 128 families.

With the promise of being provided with proper housing within a three-month time frame, around 62 families from the streets near Ripon Building were evicted and relocated to the Chennai Corporation’s shelter for the homeless in 2002. After over two decades, the 62 families have grown into 128 families. Yet, they continue to live in the same building.

The same promise of permanent homes was included in the manifestos of political parties before every election. However, it remained only on paper. As a journalistic practice, I talked to the Egmore MLA I Paranthamen to get his official input for my story. Even before the story got published, he arranged for a biometric enumeration and assured the residents of Kannappar Thidal that expeditious steps would be taken to provide them with proper housing. I was hopeful for some positive change.

However, months after that, when Cyclone Mandous hit Chennai, the 128 families spent their nights wide awake and in fear as their roofs were damaged in the cyclone and water seeped through their walls. When no help was forthcoming, either from the MLA or any officials, the residents went about finding solutions for the damages and carried on with their lives.

On December 21, I came to know that officials from the civic body visited the area with bankers and enumerated the families for loan eligibility. Over two decades after being promised decent housing, the residents have now been asked to pay Rs 5 lakhs for homes. A sum beyond their means for most of the residents.

If the plight of Kannappar Thidal residents does not make one angry, what else will it take for us to see the stark difference in our realities?

As journalists, many strangers entrust us with their stories. In many instances, we may not have the time or bandwidth to revisit many of the stories that we do. But stories such as that of the residents of Kannappar Thidal have made me realise the importance of continuously following up on an issue until the end goals are met.

Keeping with this philosophy, I am in regular contact with the residents and hope to see the story through until they are provided the homes they were promised two decades ago.

Read more: Photo story: Life in single-room homes in Chennai

Fisherfolk in Chennai and beach beautification

Finally, what is a year in Chennai without a story about its beaches?

As someone who did not grow up in a coastal landscape, beaches have always left me with a sense of awe. To me, the ocean always looked as if it locked the memories of human pain within itself and tried to spread calmness and serenity.

Like many youngsters of this generation, the Jallikattu protests changed the image of beaches for me – to one of a site of protest.

With an intention to understand why the people from the fishing community opposed the beach beautification project which was announced by the Tamil Nadu government this year, I visited Nochikuppam, a fishing hamlet next to Marina Beach.

On a fine Sunday morning, I met K Bharathi, President of the South Indian Fishermen’s Welfare Association. Little did I know then that I will be immersed in a bundle of files for the next two hours.

Bharati is an archivist. He has been preserving every single piece of document and evidence that would lend credence to the arguments of the fisherfolk against projects that could bring harm to their lives and livelihood.

I learnt from him that the history of the beach beautification project dated back to 1985. He pointed out how the project was nothing but an attempt by the government to displace the fisherfolk. The files had newspaper clippings from 1985 to the present day, tracking all the developments of such projects over the years.

Two hours after going through every document, I was left in shock. I never imagined that the same beach that gave me a sense of calm also had a history of seven fishermen losing their lives in a protest against the beach beautification project in 1985. The same shoreline saw a massacre of protesting fisherfolk by the gunfire of the police.

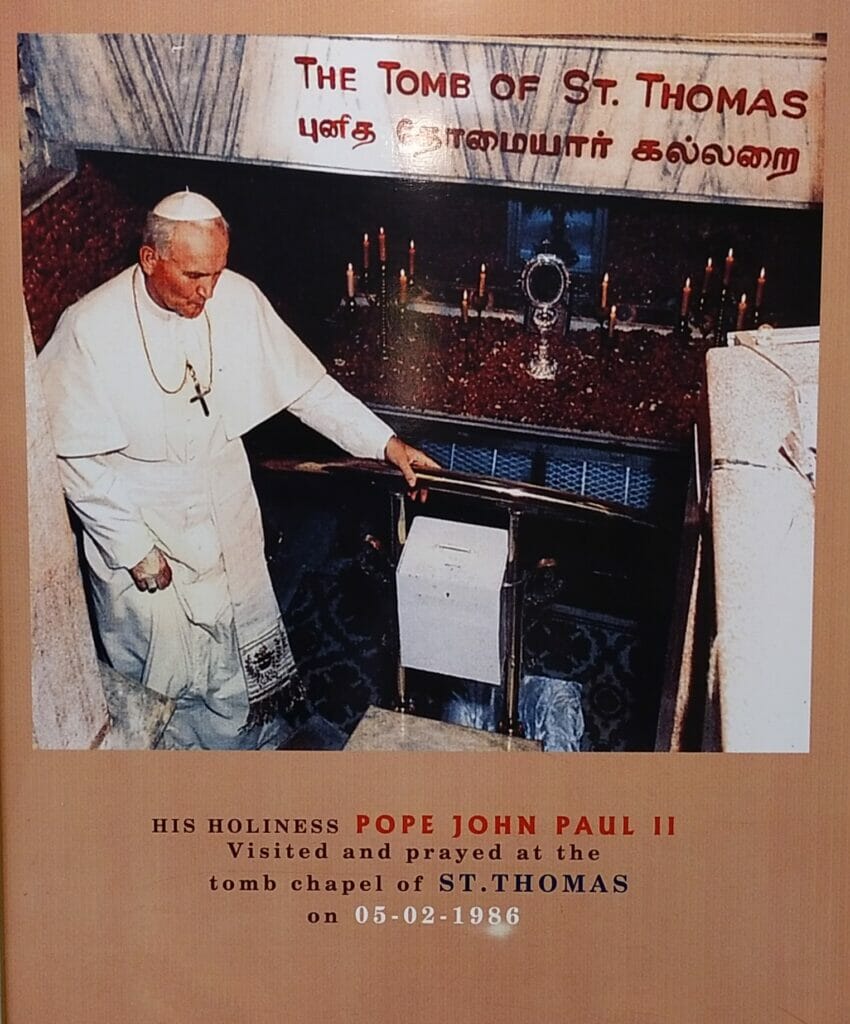

A little after this story was published, I visited the Santhome Church with a friend of mine. There, I saw a picture of Pope John Paul II’s visit on February 5, 1986. The preparation for his visit was what caused the loss of seven lives of the fishermen.

Stories like this teach us that knowing the history of a place will prevent us from falling into the traps of romanticising its beauty. Decades after the incident, I stood at the same place where thousands of fishermen protested once.

When I look at the sea, I know that its calmness and beauty are tinged with pain and struggle.

These stories have left an indelible impression on me and shaped my understanding of the city and its people. Where I see pain and suffering, I have also found humanity and hope.

Stepping into 2023, I wish to showcase more such issues but also wish for more happy endings for all those who await some change.