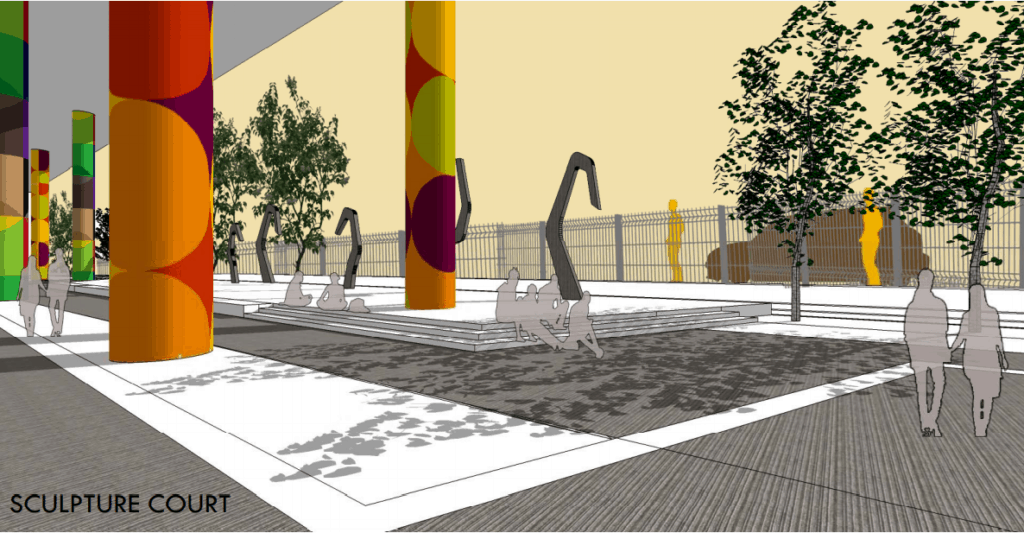

Picture this: a Miyawaki forest, a play area for children, a sculpture court and a pedestrian plaza along the Buckingham Canal, that now stands as just a conduit for sewage water amid squalid surroundings. But if plans on paper are implemented on the ground, the Buckingham Canal beautification project initiated by the Greater Chennai Corporation under the Smart City Mission, will soon transform the IT corridor (Rajiv Gandhi IT Expressway) stretch along the canal into upgraded, modern recreational spaces.

Over the years, the Buckingham canal, which holds such an important place in the ecology of Chennai, has suffered the neglect of authorities; rampant encroachment and dumping of waste and sewage have threatened its existence. In the past, various government agencies had spoken of efforts to restore the Canal, but without much result visible to citizens. In their election manifesto, the present ruling party, DMK, also promised to take initiatives to clean the rivers and other inland waterways in Chennai, which include the Buckingham Canal. Now, this Smart Cities project, aiming to give the IT Expressway running parallel to the Canal a facelift, has raised hopes once more for its restoration.

The current project

The beautification initiative, estimated to cost Rs 20 crore, is designed by LandTech AEPC Private Limited. A site study showed that the stretch is just another busy motorway and the areas along it, bordering the Canal, lack the desired features of urban commons. It has actually become a safe haven for anti-social elements. The dense inaccessible vegetation around the site and lack of maintenance make the stretch inaccessible and unusable for the general public.

Addressing these pain points, the ongoing beautification project seeks to provide recreation facilities and green spaces that complement community development and public health.

The project plan involves:

- Development of ecology through urban forestry and groundwater recharge.

- Provision of safe public place

- Provision of a well-lit open and active public environment

- Safe pedestrian crossing

- Enhanced public health amenities such as walkway, cycle track, play area, outdoor gym area

- Community development through an open plaza and creating activity zones

The eastern side of the canal will have a Miyawaki forest, cycle track, walkway and parking space, while the western part will have recreation facilities such as an amphitheatre, pedestrian plaza and a children’s play area.

While the picture projected makes for a pretty one, mere beautification may be insufficient to save the canal. The problems of the canal run deep and its revival calls for strategic planning.

Understanding the real problems of Buckingham canal

Buckingham Canal is a manmade, salt water navigation canal that runs parallel to the Coromandel Coast in a north-south direction. Within the limits of Chennai city, the waterway links Kosasthalaiyar, Cooum and Adyar rivers which are considered the lifelines of Chennai.

In the days of colonial rule, the Buckingham Canal was a channel used for intra-city movement of goods. Photographs from the past show the canal in idyllic environs with lush green edges and wooden catamarans cruising through. Over the decades, however, the Canal has been destroyed by incessant urbanisation, resulting pollution and mismanagement of the increasing volumes of waste generated in the city. The elevated corridor of the MRTS runs over the canal along the stretch and this, along with numerous other encroachments, have severely compromised its width and carrying capacity.

Read more: Can Buckingham Canal acquire new meaning for Chennaites?

Buckingham Canal beautification, as outlined under the current project, scratches only the surface of the issue, whereas the real problem has to do more with the problems outlined above.

“The smart city initiative though commendable in its overall mandate has sadly degenerated into a series of cosmetic makeovers, with no long-term sustainability in focus. Unless core issues are tackled, all these steps will amount to nothing. In the case of the Buckingham Canal, the water has to flow and it has to be free of sewage,” writes historian V Sriram in his editorial.

In 2018, Eyes on the Canal, an initiative that aims to revive the Buckingham canal, had launched an open ideas competition to transform the neglected waterway. The winning entries proposed various innovative approaches that focus not only on the canal, but also on overall climate resilience.

Team Sponge, one of the winners of the competition, looked at a 4-step water management approach integrating neighbourhood planning, regional planning and the hydrological needs of the city. “The Sponge framework slows down the runoff, stores rainwater and recharges aquifers,” Praveen Raj, Urban Designer and member of Team Sponge, had told Citizen Matters.

Their approach, in fact, was not limited to the canal but extended to the surrounding urban fabric by involving stakeholders such as the residents, local government and institutions. It was tied to the overall hydrological basin of Chennai.

Another five-member team from StudioPOD, Mumbai, who were the joint winners, also dopted a people-centric approach in their proposal. Recognising the risks of taking exclusively top-down or bottom-up approaches, the team chose a collaborative approach wherein the “local systems would work in collaboration with centralised systems” to arrive at robust solutions.

Read more: Winning ideas to revive Buckingham Canal and make Chennai climate-proof

“The main idea is to keep the community as the custodian. There has to be community participation in maintenance. The strategy will involve residents, local government, corporates and institutions as stakeholders,” Satish Chandran, Urban Designer at StudioPOD, had said at the time.

Rethinking Buckingham canal

The waters from stormwater drains (SWDs), rivers, lakes and other water bodies either drain into the canal or through the canal into the sea. Although the canal was man-made, it had a vital role in shaping the ecology of the city as it connects the three rivers of the city. However, over the years, the purpose of the canal has been severely altered due to growing urbanisation.

Environmental activist Nityanand Jayaraman raises the question of the very purpose of the canal’s presence in the present-day context. As he says, “The canal was to be a transportation canal when it was constructed, but it failed. Then, the government made it a canal that carries sewage, which again failed. Now it is being considered as flood-mitigating infrastructure, which may or may not work. Given the sea rise level, the canal may in fact pave the way for the seas to invade the city in the coming years.”

Praveen Raj, urban designer and co-founder of Sponge Collaborative, one of the winners in the Eyes on the Canal contest, also concurs with Nithyanand. Praveen states that the canal needs to be entirely rethought as a hydrological and socio-ecological linkage to tackle the city’s pressing issues of water scarcity, flooding, saltwater intrusion and socio-economic inequality. Most threats stem from long-standing negligence, which could have been avoided if the canal was considered an asset to the city.

“Across the world, cities are witnessing a paradigm shift, where waterways are seen as ecological and socio-cultural assets. In India, we never look at urban canals as an asset, rather as mere concrete conduits for carrying sewage and stormwater,” adds Praveen.

Read more: Can Buckingham Canal acquire new meaning for Chennaites?

Although it is premature to assess whether the beautification project will change the overall outlook on the canal, urban designers call for a multi-pronged approach to restore the canal and the ecology surrounding it. The canal should be looked at through different lenses and perspectives — of hydrology, sustainable urban development as well as wellness and health.

Chennai faces multiple water-related risks that will only get worse with climate change. The city’s experience with water scarcity in the summer and flooding during the monsoons has become a cyclical pattern. In this context of climate extremes, Chennai’s blue-green systems (both natural and man-made) play a critical role in managing water and its related risks. Praveen emphasises that it is imperative to think of the canal as an integrated socio-ecological corridor, that is not only a public realm requiring external upgrade but an inclusive, resilient infrastructure that could bring about positive transformation on many fronts — social, economic and environmental.

“To achieve this we need a collective sense of social and democratic responsibility; to protect and enhance the canal through institutional and grassroots-level efforts,” says Praveen Raj.

Also read:

- Alappuzha’s zero-eviction canal restoration project — a model for the future?

- Dozens of studies, hundreds of crores, but Buddha Nullah pollution still threatens Ludhiana

- Rs 550 crore spent on clean up, yet Ludhiana’s polluted Buddha Nulla only grows more toxic

- Can waterways provide the key to developing Kochi?