Can Bengaluru be water resilient? Urban water researchers Rashmi Kulranjan and Shashank Palur from WELL labs have previously outlined how the city can reduce its dependence on Cauvery water, reuse groundwater and allow lakes to act as flood control systems. However, the first step to building water resilience is understanding the different sources of water in the city, how much water is used and how much remains.

WELL labs released Bengaluru’s first water balance in October this year, co-authored by Rashmi Kulranjan, Shashank Palur and Muhil Nesi. Here are the key insights from the report.

Water management in Bengaluru

Rashmi explains the five components of a city’s water balance: “1) Freshwater coming in; 2) distribution within the city; 3) different sectors that use the water – domestic, industrial and commercial; 4) the resulting wastewater; and 5) finally, the water leaving the city.”

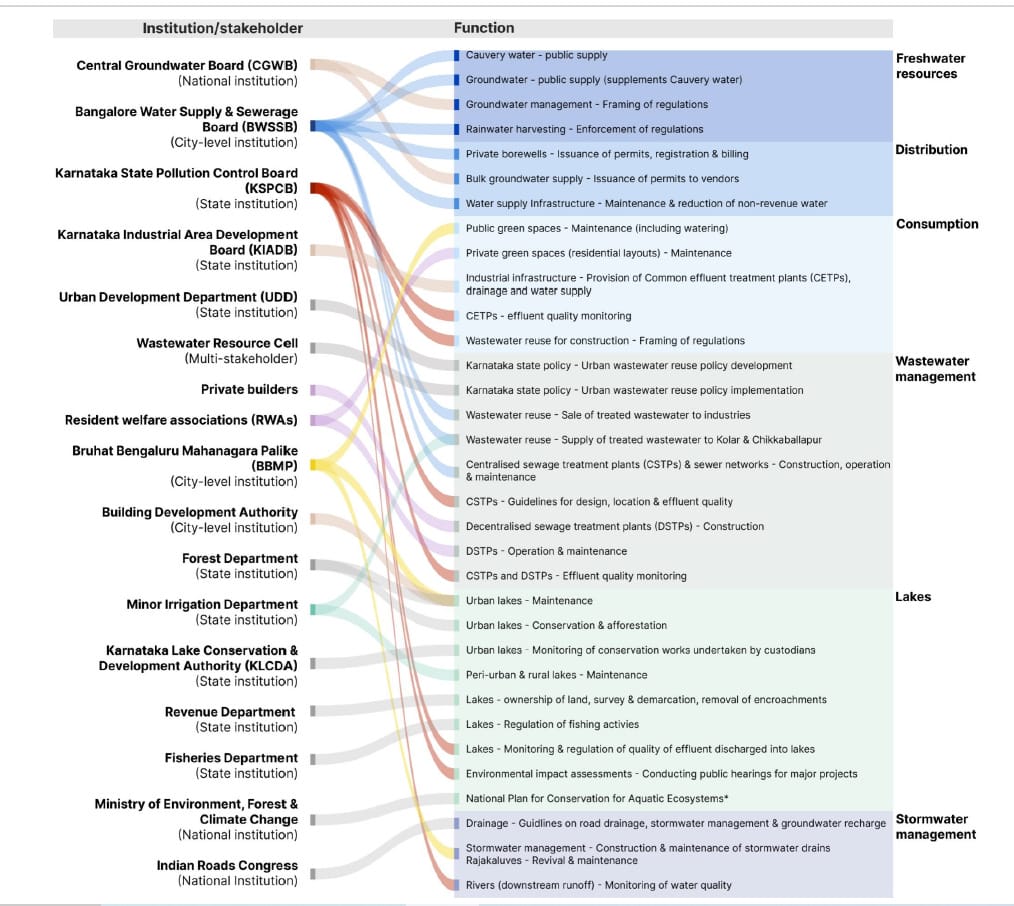

Accounting for all these components is no mean feat in Bengaluru, where several government agencies are involved in different aspects of water management.

Read more: Why researchers are developing a balance sheet for Bengaluru’s water

Multiple agencies managing water

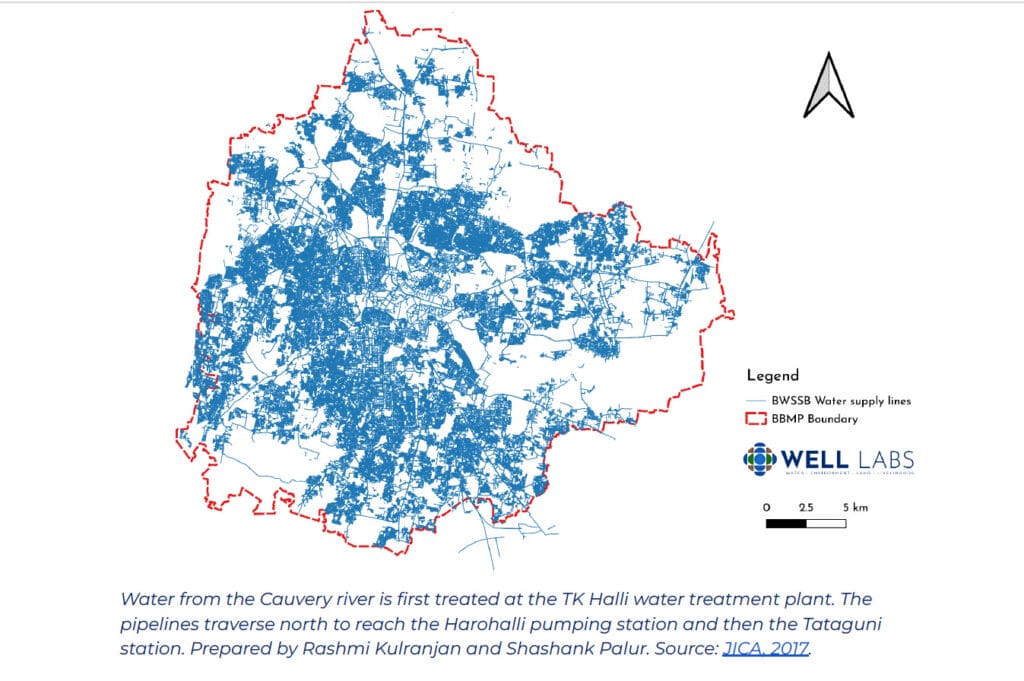

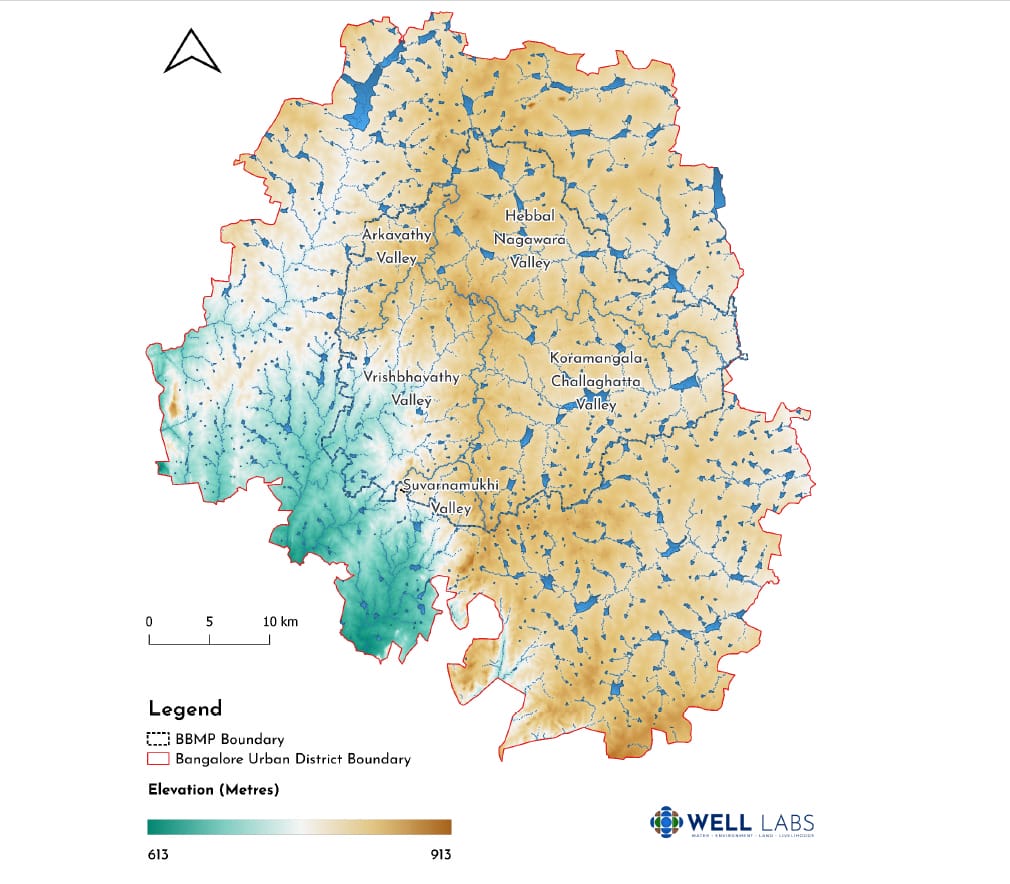

For instance, the Bangalore Water Supply and Sewerage Board (BWSSB) is in charge of supplying water and maintaining sewage networks in the city, while Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP) is in charge of maintaining lakes and stormwater drains. To carry out lake maintenance, BBMP needs to obtain permission from the Karnataka Tank Conservation and Development Authority. But, the funds for lake development comes from the Urban Development Department under the state government.

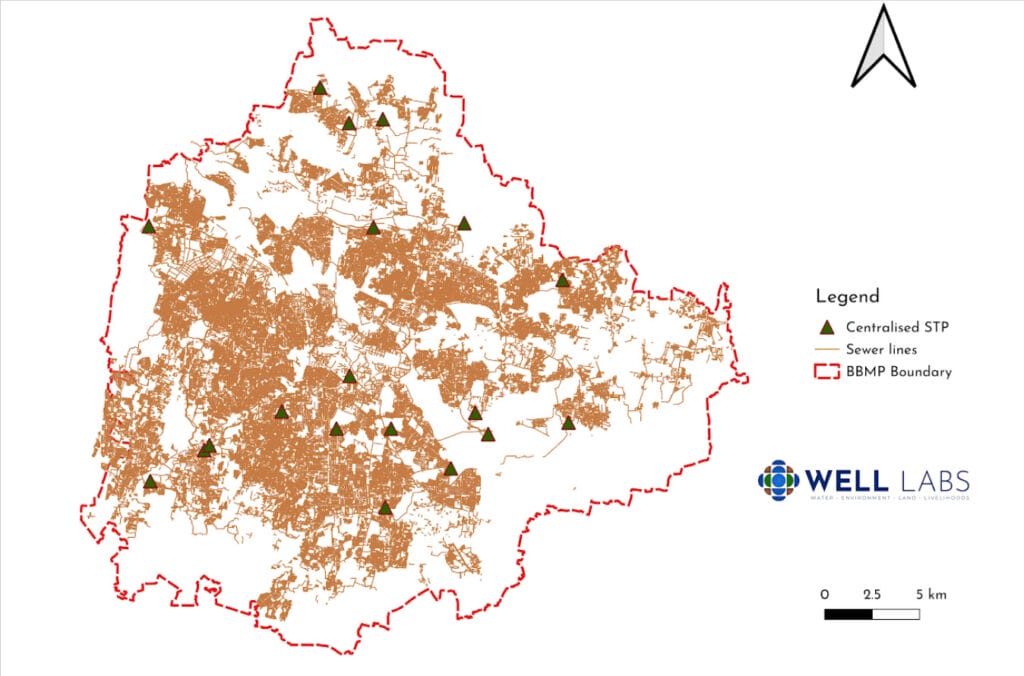

A whole range of organisations are involved in handling wastewater as well. BBMP is in charge of constructing centralised sewage treatment plants (STPs) in the city, but BWSSB is in charge of collecting pollution data from these plants.

The Karnataka Industrial Area Development Board is in charge of maintaining industrial treatment plants, while the Karnataka State Pollution Control Board is in charge of creating rules and guidelines for treating effluents. Private RWAs, particularly in large apartments, are in charge of building and maintaining decentralised STPs.

Data for the water balance

So, to create the water balance for the city, the researchers collated data from multiple sources, including peer reviewed studies, economic censuses, BWSSB, BBMP, international finance agencies like the Japan India Cooperative Agency (JICA), and media reports. “Most of these reports are old or each component of the water balance has been studied separately. What we are trying to do is to combine all of them and then see how it looks at the city level,” said Rashmi in a previous interview. Below are the key insights based on this data.

Bengaluru cannot meet its freshwater demand if the city grows

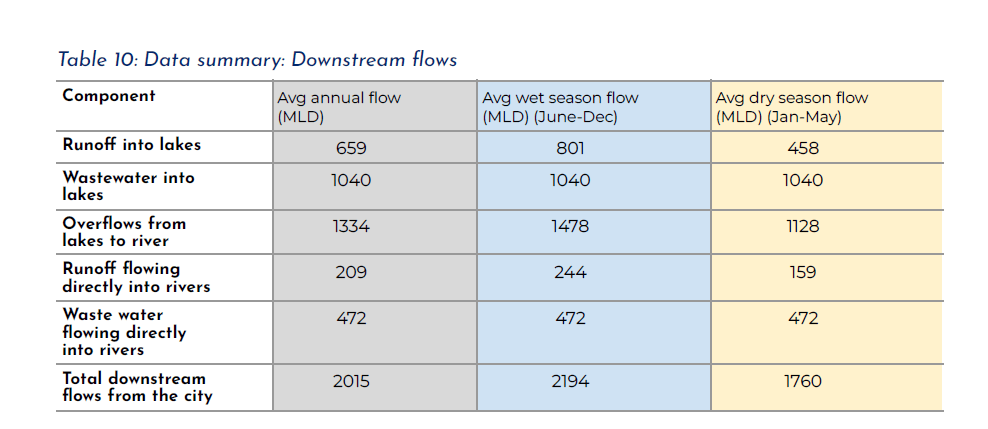

The report shows that Bengaluru’s total freshwater demand is approximately 2,632 million litres per day (MLD). Most of this demand is for domestic purposes (72%), followed by industrial demand (17%) and commercial and institutional purposes (8%).

Nearly 50% of this demand is met by groundwater while Cauvery water supply meets the rest of the city’s needs. But our groundwater table is not recharging sufficiently. The report cautions that the current resources will not be sufficient as the city’s population grows. Green spaces and lakes are replenishing just 10% of the groundwater consumed.

Leaks in piped water supply and wastewater are recharging more groundwater (30%). The more green spaces and lakes erode, the worse our groundwater recharge will be.

Rainfall in the city

Bengaluru has historically been a city with good rainfall and is now rainier than it used to be. The report shows that the city receives an average 2,149 MLD of water in the rainy season and 1,322 MLD in the dry season. But much of this rainwater goes unused. The report estimates that in the wet season approximately 982 MLD and in the dry season 568 MLD of water was being reused.

Only 183 MLD of water was naturally recharging the groundwater table. Lakes contributed to 35 MLD of groundwater recharge. A mere 19 MLD of rainwater is being harvested in the city. The authors caution, however, that rainwater harvesting data is based off media reports. There is no accurate data on how much rainwater harvesting actually happens in the city. The rest of the rainwater falls on impervious surfaces, like concrete buildings and roads, and evaporates.

The solution, according to the researchers, is to increase green spaces that are left fallow and can absorb rainwater during heavy rainfall days. An approach called sponge city that gained popularity in China.

Read more: Deluge or drought: Water researchers explain how Bengaluru can build resilience

Wastewater in the city

Bengaluru produces approximately 1940 MLD of wastewater. Around 63% of this wastewater is treated in centralised treatment plants and 13% in decentralised treatment plants such as the ones installed by apartments. But shockingly, only 30% of the wastewater is reused. This includes the water sent to rural districts under the KC Valley project. The report suggests there is a huge potential to scale up wastewater treatment infrastructure.

“A significant amount of treated wastewater in the city is going downstream, unused. This amount of water can definitely be used to offset demands, which don’t require high-quality water, such as greening, construction and other non-potable uses,” say Rashmi and Shashank.

Lakes must be free to act as flood control

Finally, the report points out that the cascading lake systems of the city played an important role in draining water from the city. But, many of the lakes in these networks are lost to encroachment and construction. Several others exist as isolated waterbodies with the connections, such as the stormwater drains, becoming lost. While this causes some lakes to dry out, it also causes other lakes to overflow and flood the city.

The report also points out that the city’s lakes receive nearly twice as much wastewater as rainwater. This means that lakes that are meant to be seasonal are continuously full of treated and untreated wastewater. These waterbodies are unable to hold rainwater during heavy rainfall spells. The excess water overflows and causes flooding.

Caveats about the report

The authors of the report remind us that the report is based on estimates, secondary data from older studies and even anecdotal evidence in some cases, such as the rainwater harvesting data. “This is our first attempt at estimating the different components at a city scale. The numbers were estimated based on assumptions and projected figures from past research and will not be exact.”

But this report is the first step towards an integrated water management plan for the city, say the researchers. “There are multiple components of water in the city, and several siloed efforts are being put into managing water locally. The challenge is that many of these efforts are being implemented on small scales and by different groups of stakeholders without an overarching strategy.” They hope the government will use the report as a starting point for city-level planning purposes.