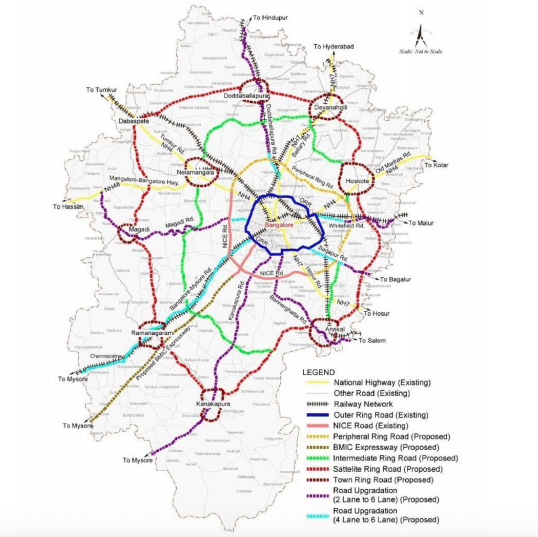

The outermost ring (in red) is the alignment of the proposed Satellite Town Ring Road (STRR)

Moin Basha used to grow ragi on a small tract of land he owned in Mugabala village in the outskirts of Bengaluru. When water scarcity and mounting debt from failed borewells forced him to abandon his primary livelihood, he looked to the city for an alternate livelihood.

Now he is a technician with an electronics service centre in north Bengaluru but continues to live in Mugabala, thanks to the improved road connectivity between Bengaluru and Mugabala, which is located close to NH 75 that passes through Bengaluru.

Road infrastructure projects like these are enabling an important transition in and around rapidly growing Bengaluru. Convenient daily commute by public transport has allowed people like Basha to take advantage of the economic opportunities the city provides while continuing to live in the more affordable peri-urban areas, i.e areas outside the jurisdiction of the Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP), but within the Bangalore Metropolitan Region (BMR).

These rapidly urbanising regions lie outside the city limits but are close enough to be influenced by the city. Road infrastructure in these areas are usually planned with the aim of decongesting the main city by enabling connectivity. However, their location in a largely agricultural landscape drives rapid and extensive land-use changes, that in turn influence natural resources, livelihoods and lifestyles of residents.

One such project currently being planned is the Satellite Town Ring Road (STRR). The project is meant to ease traffic congestion in the city by providing a bypass for inter and intra city freight traffic, so that heavy vehicles can move along the peripheries of Bengaluru without entering it. The STRR project is hugely significant for peri-urban areas around Bengaluru.

First approved in 2005, the project had stalled due to lack of funding, but is now picking up pace with shared funding between the central and the state governments. It got a new lease of life under the union Surface Transport Ministry’s Bharatmala Pariyojana program in 2018.

The 204 km-long road will connect 12 towns in Bengaluru’s peripheries. Some of these towns are intended to be developed as satellite towns to provide alternate economic centres around Bengaluru.

| The STRR project

To manage the development of STRR, a planning authority called Satellite Town Ring Road Planning Authority was constituted in 2016. The STRRPA’s jurisdiction includes:

Cost estimate for the project is over Rs 55oo cr, excluding land costs. |

Work on the first of three proposed phases has already begun. The 82-km long Phase 1 passes through Bengaluru Rural and Ramanagara districts; there are 22 major settlements along this alignment.

While transport efficiency is the inherent logic of such mega transport infrastructure projects, there are several repercussions for the people and the land on which the project is planned. One such change is that of land-use.

Changes in land use

According to the Environmental Clearance Report for Phase 1 of STRR, 87 per cent of the land within 10 kms on either side of the proposed project is presently being used for agricultural purposes. While over 1000 hectares of vegetation including 17,661 trees will have to be removed for construction of the first phase, the actual transformation will be more far-reaching.

With the construction of the new road, use of land for non-agricultural purposes will happen rapidly. An increase in construction and built-up area can be expected not only along the roads but also further away, adversely impacting natural resources and green cover. Such development will also not be restricted to individual towns, but will spill over throughout the length of the roads in a ‘ribbon’ like development of large parcels of residential and commercial real estate.

Changes in land use is accompanied by rapidly escalating land prices, especially in areas with good road connectivity. For instance, in Neraluru village in Anekal taluk, land prices rose from Rs 3 lakh per acre to Rs 1 crore per acre in the last 10 to 15 years because of the construction of the Bengaluru-Chennai highway (NH 48).

All these changes also lead to livelihood transitions.

Livelihood changes

Agriculture and allied activities are the primary occupations in the villages of peri-urban Bengaluru. Of the 7265 acres of land required for the construction of the STRR, 6663 acres are mostly private, agricultural land that will be acquired. This will impact the livelihood of farmers who were cultivating on this land.

Degradation of natural resources, climate variability and change are already making agriculture largely unviable, especially for small and marginal landholders. Coupled with the availability of secondary and tertiary sector jobs, this is resulting in people moving towards non-agricultural livelihoods.

Peri-urban Bengaluru is known for the presence of several industrial clusters like Jigani, Doddabellapur, Dobbespet, Bidadi and so on. The STRR, along with other existing and proposed road infrastructure, provides connectivity to these areas, improving access to industrial livelihoods.

But not all villages have this option – in peri-urban villages that are not connected by roads, alternative livelihoods pose a challenge. Women, especially, are unable to access jobs outside their villages and become completely dependent on male family members to commute outside their villages.

Jyothi, from Lakkandoddi village in Ramanagaram district, laments that women from her village do not go out to work despite the presence of garment factories near her village. “The roads are neither good nor safe for us to use. There are no buses to or from this village. We always have to rely on our husbands to get out of the village using our own transport, like bikes or autos.”

Aspirational changes

Road networks enable movement not just of people and material, but also the flow of ideas, aspirations and lifestyles across the urban-rural continuum. Younger people in peri-urban Bengaluru aspire to move out of agriculture and access better education, to be able to take up jobs in the city. Given the increasing unviability of agriculture, even some of the older generation seem to prefer their children taking up non-agricultural livelihoods.

Pavithramma, a small agricultural land holder in Neraluru says, “Today’s youth have no interest in agriculture as they have bigger material needs. No one wants to do physically exhausting work. They want to work in an office environment. So though it is expensive, we send our children to a private English medium school in the city. The school bus picks and drops them every day’.

Pavan, Pavithramma’s 14-year-old son chimes in, “I would like to become an engineer and work in Electronic City.”

Access to better schools, colleges and institutions of higher education is critical to this transition. In Bengaluru, a large number of educational institutions are concentrated in the city’s peripheries, and better road connectivity coupled with good transport facilities could enable the peri-urban populace to access better education, healthcare and jobs in Bengaluru and the surrounding satellite towns.

The STRR, thus, will trigger rapid and massive transformation in peri-urban areas, that can create both opportunities and challenges. With the project still in the initial stages, it must address the social and environmental consequences that this road will create, including natural resource degradation, shrinking agrarian landscape, livelihood transitions, and food security, to ensure sustainable development.

[All names in this article have been changed on request]

Curious how this affects wildlife movement.

Savandurga and Anekal are part of elephant corridors and the road cuts through their areas with no talk of mitigation.

At the same time the benefits discussed here are that people can stay in those villages but live a Bangalore life. Won’t this lead to wild life conflict? And who’ll pay with their lives? If people want to live in Bangalore, Bangalore should taken them in, provide low cost space to live. Encroaching further on surrounding forests will be dangerous. We’re already seeing the bad effects of such suburbification in Australia and California, and how wildfires are affecting more cities. Bangalore is yet to reach that stage, maybe we should take our lessons sooner.

Hope the same will be well planned and executed. Along with the road a rail facility to accommodate suburban or metro in future should be planned. Also the residential and commercial use in the vicinity should be planned manner. Also environmental issues like shrinking green covers and loss of agrain lands should be addressed and alternative should be implemented properly.

Very insightful!

Bangaloreans are one worst anti development people…First they complain of slow moving traffic and traffic jams…when Government comes up with a plan to reduce the conjunctions and jams…they suddenly remember the nature and come in Protest of it when most of them don’t even have garden or space even to place pots and would be ready to get the tree in front of their house cut for parking their cars…there can be either one of them infrastructural development or nature in huge city like Bangalore… Understand it and let Bangalore develop

Good to add more infra but at the same time there is a high risk of rapid growth of residential & commercial establishments, government must ensure that there is ample road for traffic movement & expansion without allowing builders & property owners to construct at their wish.

Along side the development there should be adequate of greenery ( mini forests every area across the stretch to have a quality air & lung space.

Rapid growth should be restricted , a proper planning adequate infrastructure be built & sanctions to be strict with zero tolerance of deviation. Cars of property owners should have own space for parking & not use footpaths & roads as parking space or garage for their vehicles in from house of buildings. oads must be 4 & 6 lanes , in the colonies it should be 40, 60 & 80 feet according to the plat dimension of that lane.

Most other important things is to avoid cables telephone & DTH cable wires running across freely & every thing should be below the ground.

Roads should be free from cart vendors & proper space for public parking should be ensured.

In all to summarize a well planned & CIP of the city should be priority having learnt lessons from past with inadequate planning & rapid growth.

import of grains is import of unemployment. But apart from being linked to the livelihood of farmers, the issue is also linked to India’s food security and sovereignty. In 2008-09, agrarian imports were just 2.09 per cent (Rs 29,000 crore) of India’s total imports. They rose to 4.43 per cent (Rs 1.21 lakh crore) by 2014-15 and 5.63 per cent (Rs 1.4 lakh crore) by 2015-16. This money should have ideally gone to the farmers, who are struggling with poverty.

Thus slowly the policies of government is to move farmers away from agriculture. One day suddenly if draught hits all over the world including India. Then even if you have money you will not be able to import. Famine having hit our country too, few rich who have stored food would survive and some 75% Indian Population would die.

Then automatically all traffic congestion will come down.