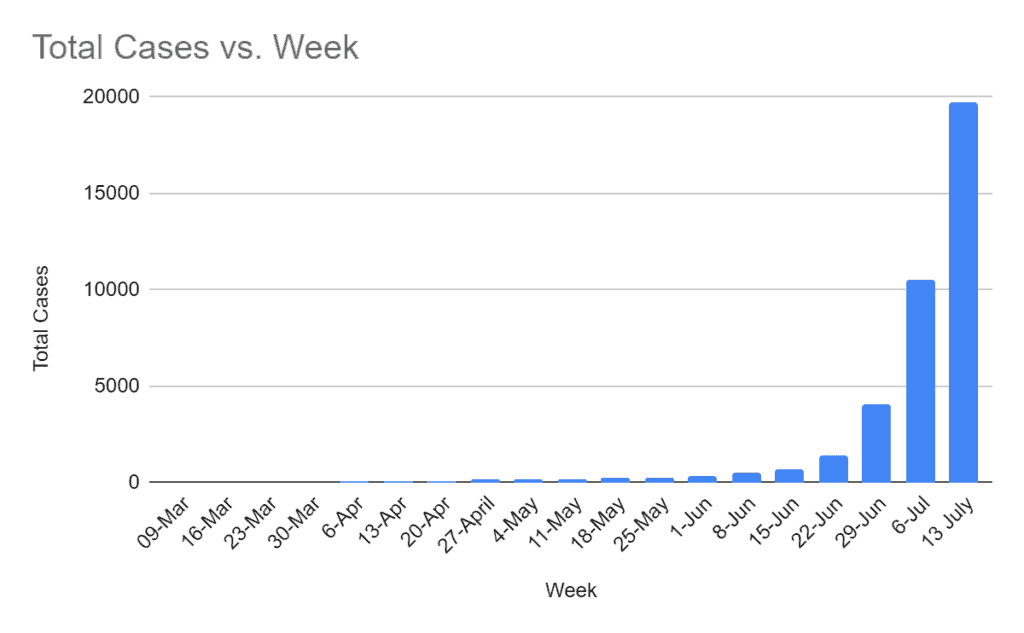

On March 9, Bengaluru reported its first COVID case, that of a software engineer with travel history to the US. Since then, the state government and BBMP have taken aggressive measures to contain virus spread. The Centre even recognised Bengaluru as a model city in COVID management. But since mid-June, the number of cases have rocketed, and now we are back to having another lockdown.

What transpired between one case on March 9 to over 22,000 cases now? Here’s a timeline of COVID cases in Bengaluru, and how the government has tried to tackle it.

March 9 – 30

Bengaluru’s first COVID case is reported on March 9. On March 13, BBMP Commissioner B H Anil Kumar orders the closure of educational institutions, malls, sports facilities, etc., and imposes a blanket ban on mass gatherings. BBMP also issues guidelines to apartment RWAs on containing the virus spread, advises those living in hostels and PG accommodations to return to their hometowns, and mandates shops to enforce social distancing.

BBMP along with Bengaluru City Police (BCP) starts visiting the homes of quarantined people, stamping them and educating their neighbours. Even before the national lockdown commenced on March 25, Karnataka government seals state borders, and postpones SSLC exams. Victoria Hospital is dedicated solely for COVID patients, and 31 fever clinics are set up to test those with COVID symptoms.

March 31 – April 13

BBMP orders those under home quarantine to send across their selfie every hour. Russel Market is shut from April 3-14 after social distancing norms are flouted. BBMP completely seals Bapuji Nagar (ward 134) and Padarayanapura (ward 135) as positive cases surface.

April 14 – April 27

On April 14, the 21-day Phase 1 national lockdown ends, and Phase 2 begins. Karnataka government caps charges for COVID testing in private labs at Rs 2,250. Journalists and police personnel working during lockdown are mandated to take COVID tests. A person without immediate travel or contact history tests positive for the first time, in Hongasandra; this migrant worker infects several others, creating a cluster. Bengaluru’s caseload touches 100-mark.

April 28 – May 11

BBMP establishes Disaster Management Cells in all 198 wards. On May 2, BBMP mandates all citizens to wear masks or to cover their nose and mouth with a cloth, when in public. As Phase 3 of lockdown starts on May 3, some businesses like salons and taxis are allowed to operate.

May 12 – May 25

BBMP launches tele-healthline for COVID-related queries. By mid-May, COVID tally crosses 200. Further relaxations as Phase 4 of lockdown starts on May 17 – complete lockdown restricted to Sundays, BMTC buses start operating.

Inter-state travel is allowed with prior approval. Government mandates 14-day institutional quarantine for all returnees initially, but soon permits home quarantine instead due to logistical issues; institutional quarantine is mandated only for travellers from certain states. BBMP publishes SOP on managing containment zones.

May 26 – June 8

Centre recognises Bengaluru as a model city in COVID management. By May end, COVID tally crosses 350. Sunday lockdown is lifted on May 30. As Unlock 1.0 commences on June 1, movement restriction – which had already been relaxed earlier – is further limited to the hours between 9 pm and 5 am. Only registration, and no prior approvals, are needed for inter- and intra-state returnees. On June 8, restaurants, malls, places of worship, etc., are allowed to open, provided they adhere to SOPs on social distancing etc.

June 9 – June 22

By June 15, 732 positive cases and 37 deaths are reported within BBMP limits. KSRTC resumes inter-state operations from June 17. Rules on institutional quarantine are relaxed progressively. Cases start rising rapidly. Government orders that instead of entire wards or buildings, only the affected house/apartment floors would be declared as containment zones.

June 23 – July 6

Authorities struggle to increase testing and treatment capacity as cases surge. The number of private fever clinics/swab collection centres is increased to 219 in Bengaluru Urban district. Government orders private hospitals to reserve 50% of their beds for COVID patients, and later releases a list of 72 private hospitals.

It’s decided that, instead of admitting all COVID patients to hospitals, those with mild/no symptoms will be sent to COVID Care Centres (CCC)/home isolation, those with mild/moderate symptoms to Dedicated COVID Healthcare Centres (DCHCs), and only those in severe condition to government/private hospitals. Buildings like Koramangala Indoor Stadium, BIEC, Haj Bhavan, etc., are turned into CCCs. Government mandates only home quarantine for all inter-state returnees since institutional quarantine centres had been turned into CCCs.

Despite these measures, several patients are unable to get admitted in hospitals, which resulted in deaths in a few instances. Sunday lockdown, and night curfew between 8 pm and 5 am, resumes from July 5. On July 6, Bengaluru’s caseload breaches the 10,000-mark.

Since July 7

State government appoints a senior bureaucrat in each BBMP zone to monitor the spread of infection. Apartment associations are allowed to set up community CCCs exclusively for COVID-positive residents with mild/no symptoms. Government issues show-cause notice to two hospitals for refusing treatment to COVID patients. It also orders all hospitals to display details of bed availability at their registration counters.

As the one-week lockdown began from July 14, BBMP released a portal that gives details of bed availability in hospitals. So far, the city has had 22,944 COVID-positive cases including 438 deaths. On July 15th alone, 1975 new cases and 60 deaths were reported.

[Siddhant Kalra contributed to this article]