Susheela* begins her work at 6 am and finishes around 2 pm. During the eight hour work shift, the 45-year-old pourakarmika rarely takes a break. She tries her best to only drink water and take toilet breaks twice. She controls herself until her morning meal at 10 am and final call at 2 pm at a local government school in Thindlu, in the Vidyaranyapura ward in North Bengaluru.

There is a public toilet next to the school, which Susheela and nearly 50 pourakarmikas in her group or mustering use. “I try to avoid drinking water until my breaks ,” she says.

Susheela works in Canara Bank Layout, a largely residential neighbourhood, with leafy green streets and big houses. If nature calls while she is sweeping up fallen leaves and plastic, which the residents have not bothered to segregate, well, she’s in trouble.

“I have to find an empty site with a bush,” she says. But this is risky because there are always people on the streets and houses surrounding these empty sites. “If somebody catches me, it will be so embarrassing,” she says smiling.

Cabins of convenience

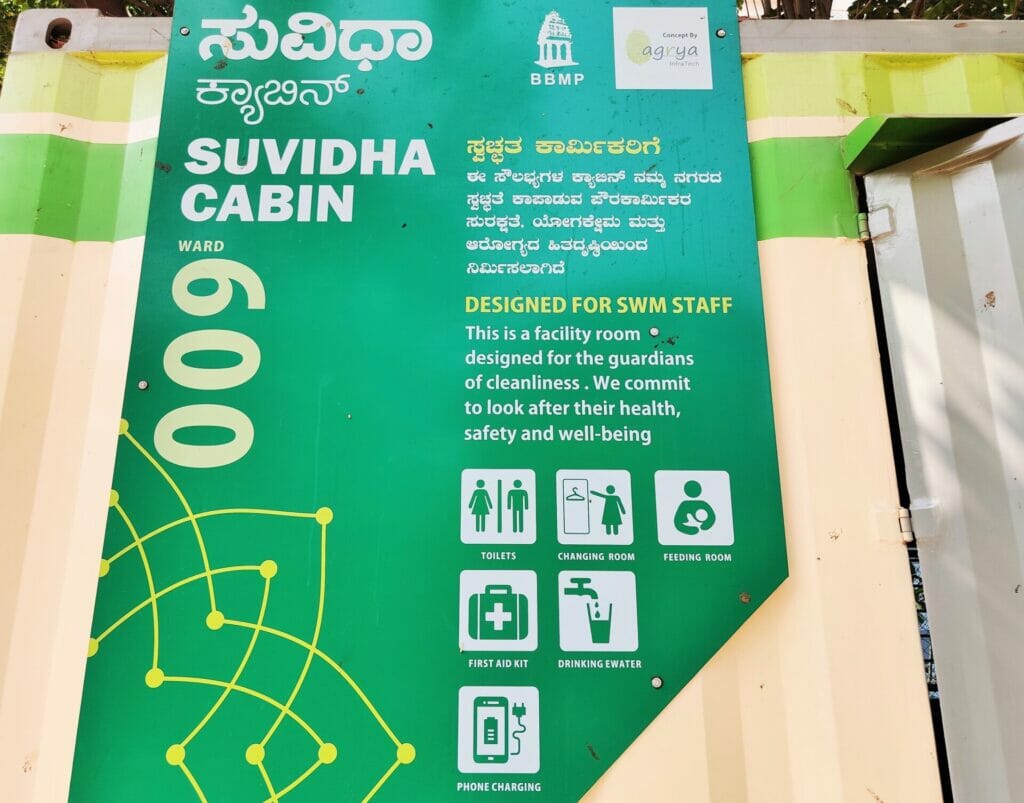

It was to avoid such scenarios that the state government announced the making of Suvidha cabins for pourakarmikas in 2020. The plan was to literally place re-furbished shipping containers, measuring 20 X 8 X 8.6 feet, in every ward of the city.

These cabins would have changing rooms and separate toilets for men and women. There would also be charging points, first aid kits, a fan, and space for women pourakarmikas to breast-feed their babies. Each cabin would cost Rs 8 lakh.

In 2020, BBMP promised that the city would have 225 cabins within six months. As of early 2023, there are only 68 suvidha cabins.

Vidyaranyapura ward, where Susheela works, has one such Suvidha Cabin in the compound of the BBMP ward office. Siddharaju, a health inspector for the ward, opens it for me.

Inside is little changing room and a clean toilet, enough for one person. The opposite wall of the rectangular cabin is made up of cubby-holes for pourakarmikas to keep a change of clothes or other items. There are around six charging points and a wall-mounted fan. The rest of the floor is bare.

Around four to five people can sit in the cabin comfortably, more if they squeeze together.

Read more: What can Bengaluru expect from BBMP’s 14.4-crore plan to send pourakarmikas to Singapore?

Who uses Suvidha cabins?

Each ward in Bengaluru has close to 200 pourakarmikas, as per data released by BBMP in 2017. The Vidyaranyapura ward has 200 pourakarmikas. The entire city has at least 25,000 pourakarmikas by conservative estimates. The neighbourhood where the Suvidha cabin is located has around 50 pourakarmikas, according to one of the supervisors in the area.

Siddharaju readily admits that the Suvidha cabin cannot accommodate everyone. It was not meant to because of space constraints, according to the health inspector. The pourakarmikas in the area are free to drop in and use the cabin’s toilet or charge their phones and store their day clothes. Around three to four people may come by in a day.

“All 50 people in this muster cannot use the cabin at the same time,” he says. “But they use it when needed.”

I spoke to some of the pourakarmikas assembled for their morning meal at a hall next to the Vidyaranyapura ward office. A few workers said they had used the bathroom in the cabin occasionally. However, they could only come to the cabin during the scheduled meal break and when their shift ended; it was too far to access at other times.

On both days that I visited, not one pourakarmika was using the cabin. Most rested with their colleagues in the eating areas or by the roadside.

The inconvenience of Suvidha Cabins

For pourakarmikas working in Thindlu and other neighbourhoods in the Vidyaranyapura ward even this was out of question. Susheela, for instance, works in Canara Bank Layout, which is over 2.5 kilometres from the Suvidha cabin.

She and her colleagues use a public toilet adjacent to their mustering point – a government school. They eat their meals sitting on a dirt floor in the school grounds and wash at a tap outside the school. There is some shade from a Banyan tree, but no shelter from rain or dust that the wind sweeps up.

“Even in the rain, we huddle under the parapet. We are not allowed to enter the rooms, because they say we will dirty it,” says 70-year-old Nagamma*. But the chief complaint she and her colleagues have is about eating outdoors with no shelter and in the dust.

“Everyday I sweep dust; it gets in my eyes and nose. At least when I eat, I should not taste dust,” she says.

Siddharaju says that there were plans to install a second Suvidha Cabin in the ward in 2021, for pourakarmikas like Susheela. BBMP had the cabin ready and had even identified a piece of land that belonged to the civic body. The plan fell through because the residents in the area objected, according to the health inspector.

Read more: With meagre pay and unhealthy conditions, why do Bengaluru pourakarmikas continue in their jobs?

“They [residents] said pourakarmikas would dirty the area. There was also a temple opposite where the cabin was to be placed. That was the objection,” he says. Senior BBMP officers at that time did not object to this blatant casteism or go ahead with their plans. “They were worried that someone might get upset and damage the cabin,” he adds.

This year BBMP announced that they would not install the remaining shipping containers. Instead, they would build 52 permanent suvidha cabins on 20×30 feet sites across the city. The reason given was that the cabins were cramped. It is not clear why BBMP realised this only three years after announcing the plan and a year after the first cabin was installed in 2022.

Who wants Suvidha Cabins?

However, it is clear that the agency did not consult pourakarmikas about what facilities they needed.

Back at the Government High School in Thindlu, I showed the pourakarmikas photos of the Suvidha cabin and asked them what they thought of the facilities in the cabins.

Not one worker felt there was a need for a charging point as they all charged their phones at home. No one to their knowledge had worked while carrying a breastfeeding infant. The feeding station, which was just the floor of the Suvidha cabin, was not needed according to all the women there.

Even the changing rooms were unnecessary according to them.

They only wanted two things: a sheltered place where they would sit comfortably and eat, away from the dust and heat, and a toilet within a minute or two of their work stations. “Even if they put a suvidha cabin, if it is ten minutes away by walk, can I leave my work and come?” asks Nagamma.

*Names have been changed on request