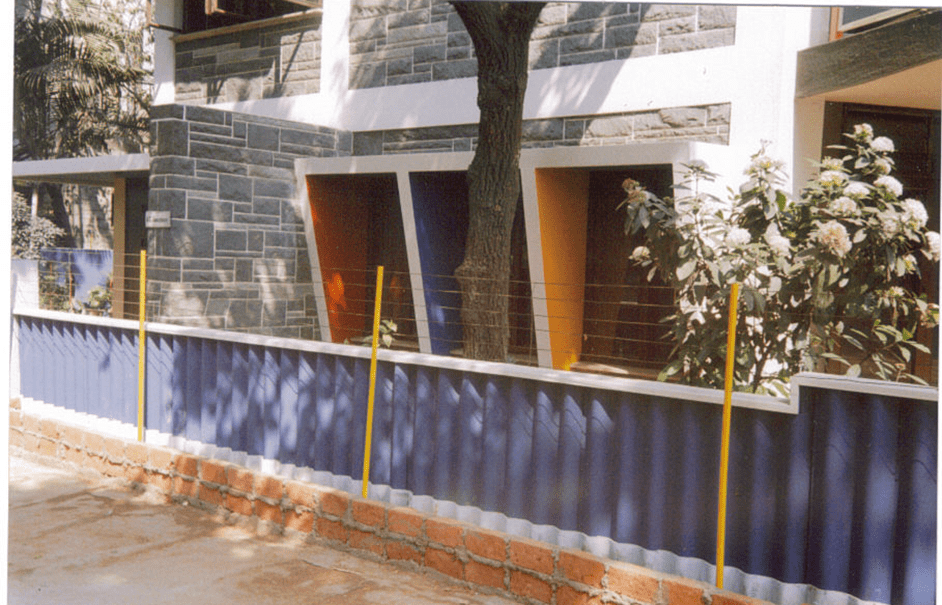

Driving along Millers Road, you suddenly notice an undulating compound wall that appears to be made out of sheets with delicate wires strung across to create a sense of enclosure. You look up and notice a stone facade punctured by large windows, flat chajjas above, glass panels as balcony railings, metal verticals – as you absorb all these details in passing you realise that the house was probably designed by an architect, and you are also able to take in certain features that remind you of a particular architectural style…

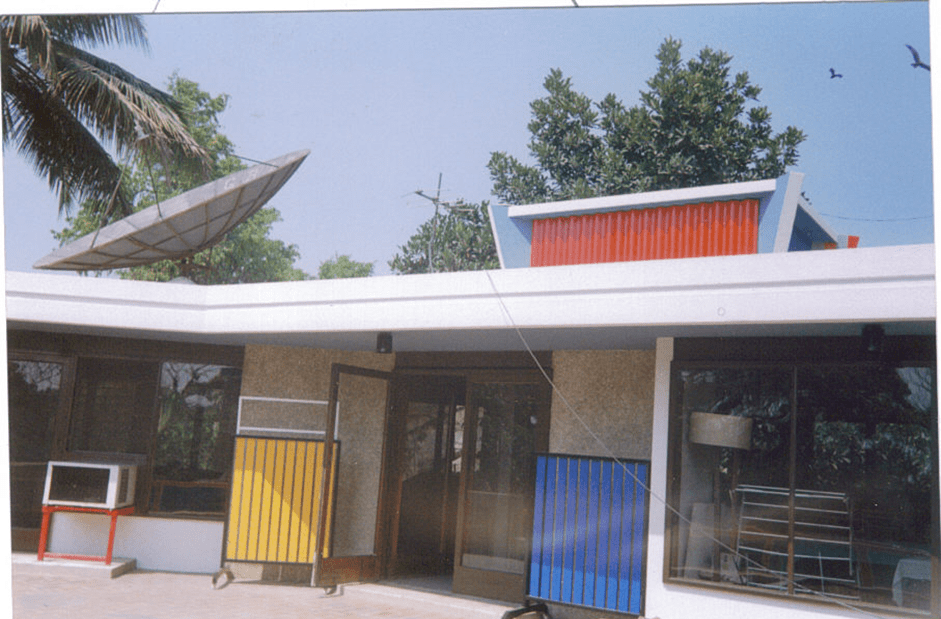

Figure: the exterior of the house – note the granite walls, primary colous to the chajjas and sheet compound wall

Years ago as a student of architecture, I remember plodding my way through six semesters of the text heavy course ‘A History of Architecture’ starting with the great River Valley constructions of Harappa and Mohenjodaro to Medieval, Modern and Contemporary styles. It was a vast time span to cover and many of the styles we studied were more popular in Western Europe and North America than India making it difficult for us sometimes to visualise the difference between, for example, Baroque and Rococo or Romanesque and Neo-Classical. Over the years travel to regions where these different styles originated or were popular made it far easier to understand the differences in their conception and application. And also make linkages across these styles that were not apparent when we studied them in texts.

| See also: This article follows the Citizen Matters feature on vintage homes of Bangalore by Nikhil Reddy: These olde Bengaluru houses. |

However I have gradually come to realise that though such various expressions of architecture and design may not be obvious they did and do leave a mark worldwide. One only needs to look around and find them. For e.g., Bangalore’s colonial period churches which bear the mark of their origin like the French Romanesque influenced St Francis Xavier Cathedral or the Neo-Gothic St.John’s or even the Neo-Classical St.Mark’s church.

One such style which was a personal favourite of mine due to its use of primary colours, and breaking down of forms to their basic expression was the De Stijl (‘The Style’ in Dutch) movement. I was fascinated by this style based on the little we were exposed to it in our lectures and the overhead projector images that we were shown as part of the class. And one day last year I came across this house in Bangalore which to me seemed to be influenced by this movement – Shererock. Even the name sounded magical!

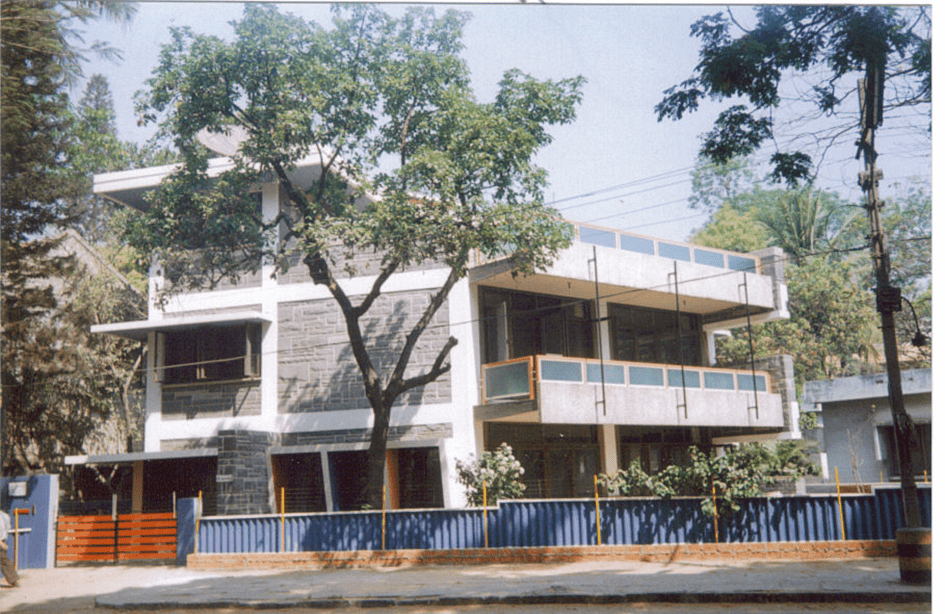

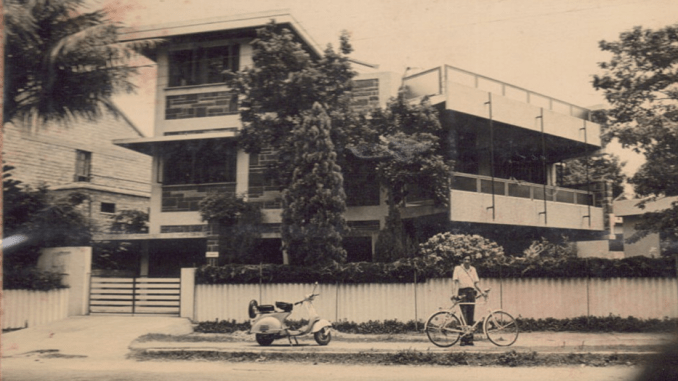

Figure 1: exterior view of the house in 1984 – note the use of dressed granite for the walls

While my first and only visit to this house was a poignant reminder of time passing by – it had been shut for months and there was a thick layer of dust everywhere, it was clear that the house still held a charm of its own, the quirky interiors (they looked custom designed and I found out later that they indeed were) and sense of space stayed with me.

The house located on Miller’s Road in Benson Town was designed by the architect Amir Jairazbhoy as his residence cum studio. He lived there till 2011 when he passed away. Vivek, his son, says that the family bought the land in 1970-71 and his father had designed and constructed the house by 1973 – he intended it to be his signature work. How did the house get such an unusual name? Vivek shares an amusing anecdote.

A brief debate raged within our household regarding the most appropriate spelling for “Shererock” (pronounced “Sheer Rock”) [because of the use of sheer granite walls in its construction]. Alternatives considered were “Sheerrock”, “Sheer Rock”, and “Sheerock”. My parents’ eventual choice was by far the most elegant. However, in some sense, it may have backfired, since many members of our erudite Bangalore gentry unhesitatingly pronounced the name “Sher-e-Rock”, as in “Sher-e-Punjab”, much to my parents’ chagrin.

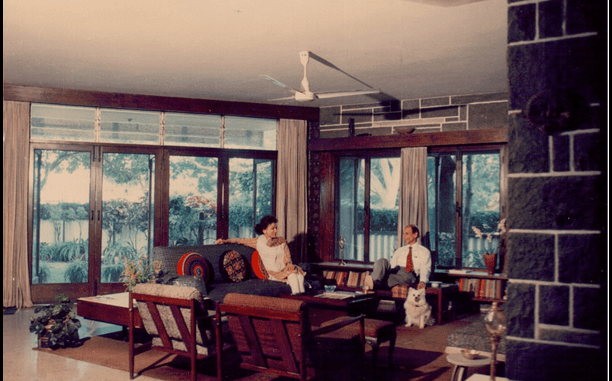

Figure 2: interior view showing one of the ‘sheer-rock facades’ of ‘Shere-Rock’ taken in 1980 (Amir Jairazbhoy seated on an armchair of his own design)

Amir Jairazbhoy hailed from an intellectually-inclined business family originally based in Mumbai. His father and uncle were Islamic scholars, another uncle was an ethnomusicologist while his wife was a visual artist (painter) and Chief Editor of Eve’s Weekly in the 1950s.

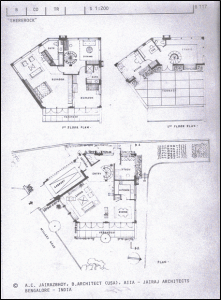

Figure 3: Floor plan of ‘Shere-rock’ submitted for the Habitation award – note the minimal number of walls to make it appear like the spaces flow into each other.

Jairazbhoy studied Architecture at the University of Washington, Seattle in the late 1940’s. He then pursued his passion for Art and Interior Design for about two years at the Chouinard Art Institute in Los Angeles, California. On returning to India, he set up his architectural practice in then Bombay, producing award-winning designs such as the ‘Bertorelli’s’, ‘Khyber’, and ‘Chinese Room’ restaurants. He moved to Bangalore in the 1970s.

Vivek says his father found inspiration in the works of the seminal 20th Century architects Frank Lloyd Wright and Mies van der Rohe, which seems appropriate because the De Stijl movement was influenced by Wright and the movement’s philosophy was carried forward by Rohe.

The house was one of three Bangalore based houses designed by Jairazbhoy all of which won the Swiss International Habitation Space Award – the Silver Hexagon which Shererock won in the year 1980. The family has managed to trace the names of the other two houses – the Sippy house and the Talwar House but they are unsure of the location and if the houses still exist. (If you know of these houses, do mail us at bengaluru@citizenmatters.in)

Amir Jairazbhoy’s work shows a deep passion for his art.

In one of his previous projects (not Shererock) in which he was keen to generate a “naturally fractured appearance”, Amir Jairazbhoy actually insisted, much to the consternation of his client, on taking large slabs of expensive stone up to a height, and dropping them on hard ground to produce natural fracture! Once the stonework was completed, the client was completely amazed and even more completely satisfied.

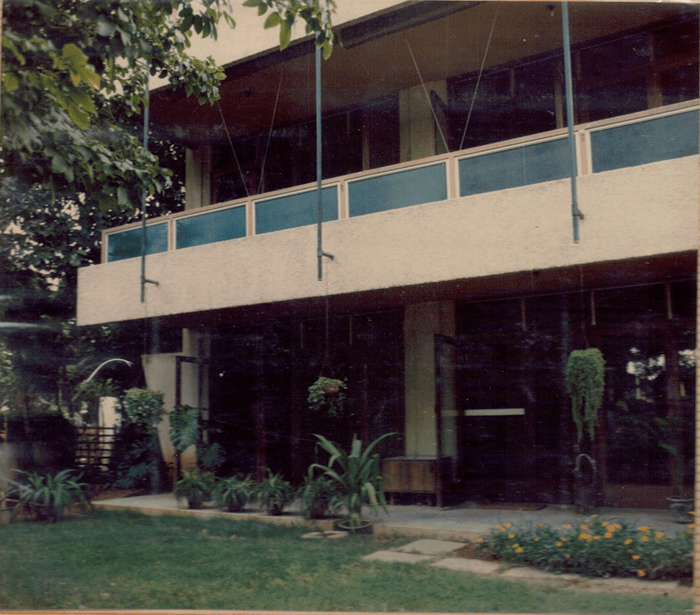

Figure: view of the balcony from the garden – the railing infill panels are in tinted glass

Figure: view from the terrace – note the use of primary colours – reminiscent of the famous artist and De Stijl proponent Piet Mondrian. Much like the compound wall, these panels are also of asbestos – a reminder that not all materials we consider ‘wonder solutions’ do stand the test of time and / or health factors!

Figure: partial view of the rear facade

Figure: An old photograph of the living room and the garden beyond – note the absence of grills in all openings

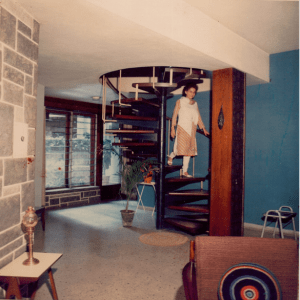

Figure: view of spiral staircase leading to upper floors

Another interesting facet to Amir Jairazbhoy lies in the fact that Shererock was home to a fairly extensive art collection. Vivek shares more:

M.F. Husain was his close friend and painted murals on several of his architectural works. This was in the early 50’s, when Husain was not yet the prominent figure that he later became. In support of Husain’s career, my father recommended him to friends and colleagues in Bombay, predicting that he would become a great artist one day. The many Husain paintings that hung in Shererock were bought because Dad felt that they had instant appeal and were quite different from those of other Indian painters of that period.

Figure: view from across the street in 1981

Bengaluru is likely home to many such architectural gems that are forgotten or not generally remembered. Such collective amnesia on the part of a city seems undesirable especially at a time when there is ongoing debate on topics like what ought to constitute urbanscapes or make a city’s identity and whether it is possible to move forward without acknowledging the past? Do urban history and heritage have to only be about linear age value i.e. does something have to be ‘100s of years old’ to be remembered or celebrated or even acknowledged? Could there be other significances or values – like intellectual and / or cultural contribution to a city and its identity? A good case in point is the recent demolition of the 1972 Hall of Nations building at Pragati Maidan complex, New Delhi (designed by architect Raj Rewal), by a short sighted city corporation.

This article has inputs from Vivek Jairazbhoy, the son of Amir Jairazbhoy. All images courtesy: Vivek Jairazbhoy

Do you know of other such architectural gems in Bangalore that still exist – structures designed by architects for residential or public usage that you feel deserves a mention? Write to us at bengaluru@citizenmatters.in and we will try to feature it.

Beautiful house, but I think it is embroiled in a legal battle between son and second wife. I have been living in the area since the late 80s