In the last few months, many apartments in the city were pulled up for not operating their Sewage Treatment Plants (STPs) according to standards. Apartment associations had complained that the standards set for STPs were too stringent and that officials did not follow clear guidelines during inspection.

Click here to download The STP Guide: Design, Operation and Maintenance

A guidebook released by the Karnataka State Pollution Control Board (KSPCB) on November 1st addresses these issues. The book was authored by Dr Ananth S Kodavasal, environment expert and Founder of Ecotech Engineering Consultancy.

Dr Kodavasal, in the book, has recommended that the criteria for turbidity (suspended solid) levels in treated water be relaxed. Currently, treated water is supposed to be of high quality, with maximum turbidity of 2 NTU (Nephelometric Turbidity Units).

The book recommends that the level be relaxed to 10 NTU, since even drinking water is allowed to have 10 NTU turbidity as per BIS 10500 – Indian Drinking Water Standards. Especially since treated water is used only for car washing, toilet flushing etc.

KSPCB Chairman A S Sadashivaiah says that this can be allowed since other criteria set by the guide are quite high. “During inspection, if all other critiera are found to be complied, we can tolerate turbidity level up to 10 NTU. Board had previously set stricter criteria so that there would be no psychological barrier for people to reuse treated water,” he says.

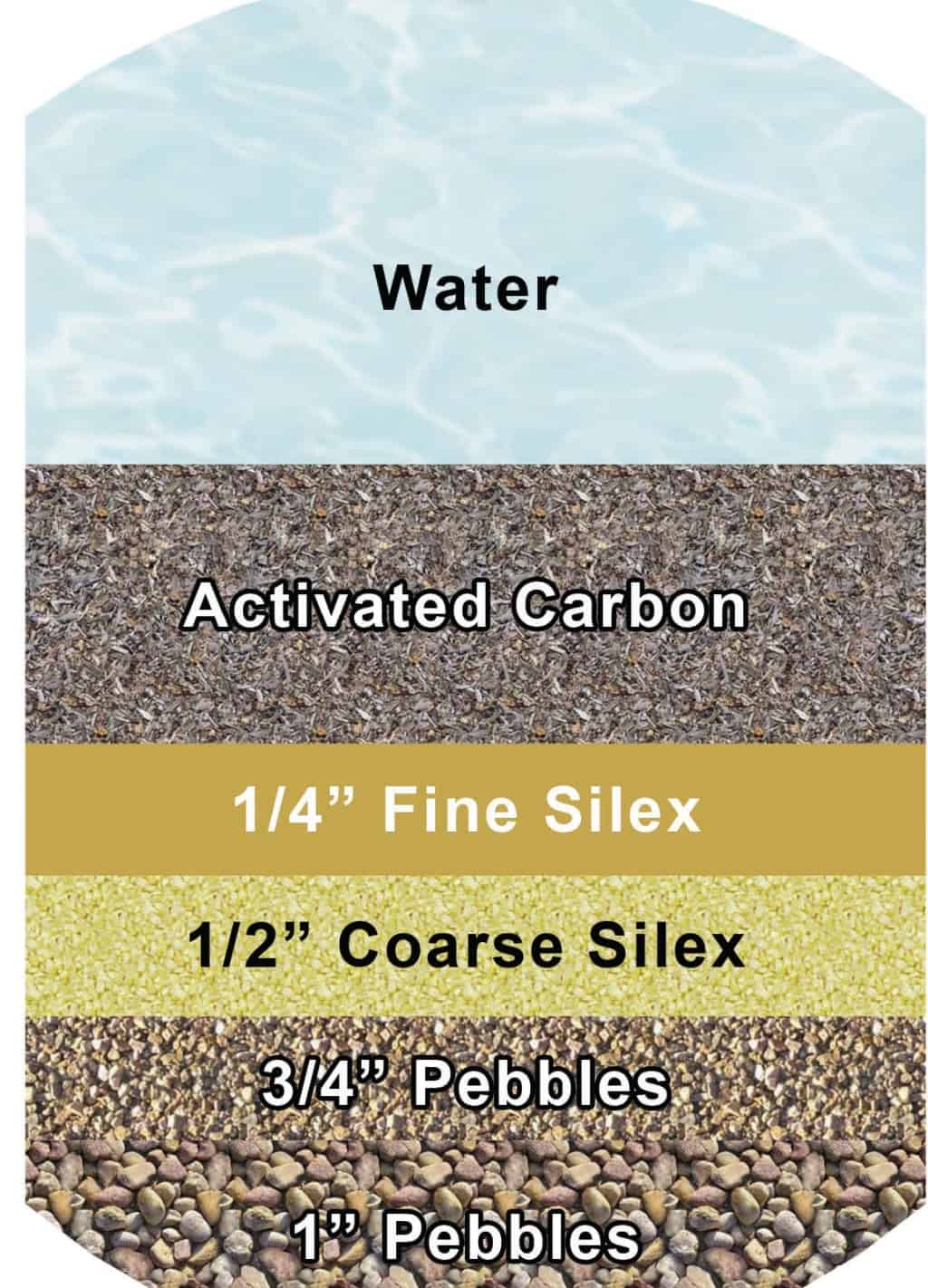

Sketch of the Actived Carbon Filter, the tertiary treatment unit in the STP, refines it in the final stage. Pic courtesy: KSPCB

The guide clearly defines the STP parameteres set by the Board. It also gives a checklist that the Board officials can follow during their inspection, which may make inspections more accountable. “We already have parameters, but they are broadly defined; different officers use different criteria during inspections. From now, this checklist will be followed,” says Sadashivaiah.

Currently inspections are mostly based on visual checking of the system rather than tests or measurements. The guide gives four methods – visual, physical measurements, performance tests and documentation check – to assess the engineering and operational efficiency of STPs.

The guide also details good practices in design, engineering and maintenance of STPs for builders who build STPs, as well as apartment owners and offices that maintain them later.It has detailed information with sketches about each unit of the STP, its functions, design, operation and maintenance.

Troubleshooting for each unit is mentioned. According to the book if these criteria are met, STPs would function 10-15 years without major repairs and at minimal cost. It encourages recycling, saying that treating one KL of water would cost only Rs 20-30, which can then be reused to prevent water scarcity. It also explains how treated water can be disinfected for reuse, and how sludge can be handled.⊕

Dear Ms. Navya :

Thank you for your coverage of the STP Guidebook, where you have captured the essence and the purpose of the Book in a very precise fashion.

However, there are same factual errors in your report on the STP Guide Book :

1. The Author is Ananth S Kodavasal , not Anand

2. The Guide Book cannot “revise” stds. laid down by the KSPCB. It was only my view on the subject, and it is now under consideration by the KSPCB

3. The Guide Book has not “relaxed” quality criteria of treated water. That is, and remains the prerogative of the KSPCB

I am gratified to note also that you have grasped the technical aspects of the Book to a nicety, which was indeed the purpose and intent of the Book – to spread awareness to the citizenry of Bangalore, and indeed others interested in the working of an STP, treatment, recycle and reuse of water.

Hello Dr Ananth, have got clarifications from KSPCB on these points and have fixed them. Thanks

Hard copy of the guide is now available at the Accounts Section of KSPCB Head Office in Church Street, at the cost of Rs 200.

Hello Mr. Ananth & Ms. Navya,

What is guideline for disposing STP treated water, which meets water quality criteria? Currently our Apartment generates excess water (after using it for gardening), which we need to dispose off. we still don’t have sewage line in our area. Can you please suggest economical way ti dispose off water. Since apartment is 6-7 years old, connecting these to toilet flush is cost intensive process.

Thank You

Sanjeev