The standard of roads in Chennai city is something that the common citizen is all too familiar with. Newly laid roads last a year at the most, after which some patch work has to be undertaken. Otherwise, a total relay is called for within 2 to 3 years, by which time the whole road surface is battered badly. Thus the lifecycle of a road in Chennai usually stretches from one monsoon to the next. World standards indicate asphalt roads last anywhere around seven years; why, then, are roads in Chennai of significantly lower quality, needing constant repair and frequent relay?

Facts discovered and released by Arappor Iyakkam, an NGO focused against corruption, pertaining to a single road scam and one in a series of expected ones, probably explains why.

On March 23, 2015, the Chennai Corporation approved a Rs. 345-crore road relaying project for 151 roads in the city. As per a council resolution, road repairs and relaying were also to be taken care of by the same contractor who had laid the road.

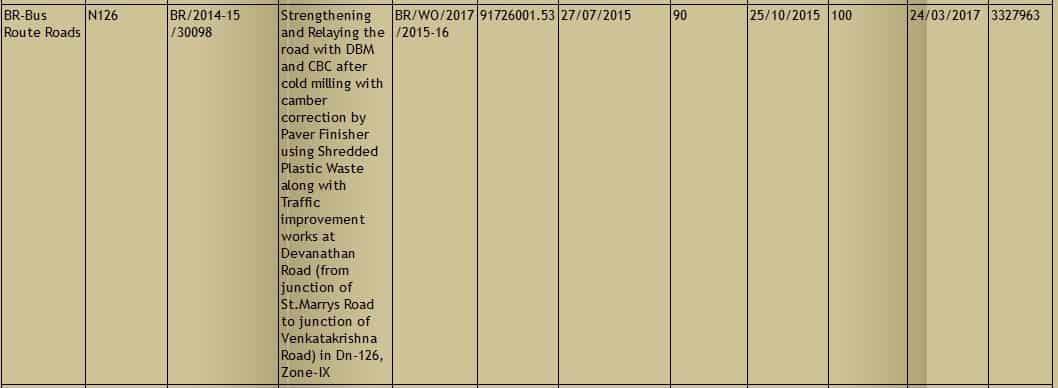

One of the roads under the project was Devanathan Road in Mandaveli. The contract for this road was given to a contractor named J Santhanam for Rs 36,97,776 with a three-year guarantee period for the quality of the road. In May 2016 the contractor laid the road. Just a couple of months later, in July 2016, Metrowater started digging up the newly laid road for its departmental work. This was completed around August-September and was widely reported in the press then, more so for the inconvenience that had been caused to the people due to the works.

On September 24th, a work order was issued to a company called MPK enterprises for patch work on Devanathan Road for Rs. 2.25 lakh, in violation of the aforementioned council resolution passed before the contract was awarded. In the month of October, the road works were completed; Arappor volunteers had then taken snapshots of the same, showing that the road had been re-laid without milling and that vehicles were plying.

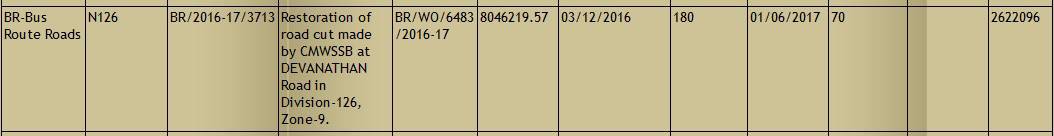

In another inexplicable development, in December 2016 another work order worth Rs 26.5 lakh was issued to the original contractor, J Santhanam for patchwork on the same stretch. In effect therefore, within a period of a year, around Rs 65 lakh was spent on a single 100-metre road, but even today, the condition of the roads is far from what is desired.

Incidentally, I personally visited Devanathan road in Mandaveli on November 23, 2017 to verify the facts on the state of the road and also to gather some public perception of road works in the city. I found it quite interesting that the battered road had patchwork done at a few spots earlier on the same day, which could also be due to Arappor’s exposé.

You can view the findings of my survey on Devanathan Road at the Youtube link here: https://youtu.be/E5XLP62C2Ng

Citizens wait for answers

The case of Devanathan Road, of course, calls for an explanation of why the contract was not awarded to the same contractor who had laid the road in May, and was instead given to MPK constructions in clear violation of the Council resolution. There is also the question as to why the Rs 26.5-lakh work order was presented to Santhanam in December when there was already a perfectly laid road.

But this particular instance of corruption also raises larger questions to be posed before the Chennai Corporation’s road works department and its contractors:

- Road Milling is supposed to be compulsory for roads that fall on bus routes. Why is this not carried out as seen in this case and several others around the city? Even if milling is done, is it being done as per the technical specifications and to make sure that there is no increase in road height?

- The Corporation claims that roads are three-layered to prevent easy wear n tear; if this is indeed true, then how come the roads are in such a condition today? Were there no lessons learnt from the 2014 exercise in which the Corporation had tested 1300 odd roads and found major anomalies?

- Is the road warranty period being enforced at all on the contractors for poor quality of work? When Devanathan Road is under warranty, how is it that the road is filled with pot holes today?

- Why is there no synchronization with other state agencies such as CMWSSB, TNEB etc. before a new road is laid out? Is there a lack of a process in streamlining this, which has resulted in a loss of Rs 37 lakh to the exchequer in this case?

What is to be seen now is whether the Chennai Corporation will put out all facts pertaining to the above exposé in the public domain. Will it make sure that its ombudsmen make inquiries into this issue without bias and punish the guilty? And most importantly, will it make the contractors liable for the poor quality of work carried out by them? Citizens really deserve to know.