“Primary Education is grass-roots education on which the pillars of the future get built,” says Raghav Kataliya also known as Raghu Ramakdu (toy) of Mithyala Prathmik Shala in in Saurashtra region in western Gujarat. “I am happy that the concept I started in 2020 is now being implemented across Gujarat.” The 32-year-old math teacher is known for his creative teaching skills. For instance, he uses an umbrella to teach patterns and his shirt to teach multiplication. Worried about his primary school students missing out on their studies during the lockdown, Raghav conducted classes for his students in batches in open spaces.

Though the government appointed experts panel had yet to submit its report on reopening of lower primary school classes, Gujarat Education Minister Jitu Vaghani announced on November 21st that schools with standard 1st to 5th could open physical classes.

Most schools were, however, not prepared to restart as they had not put COVID precautions in place. Time was also needed to contact parents of children to obtain their consent.

Also, with only 50% attendance permitted, only a few students turned up at schools that did open.

For the rest, it was outdoor classes, which had begun in June as part of the programme to ensure primary education continues despite the lockdowns and other restrictions.

This is the story of how teachers and students adapted to and came to like this new scheme of taking education out to the streets.

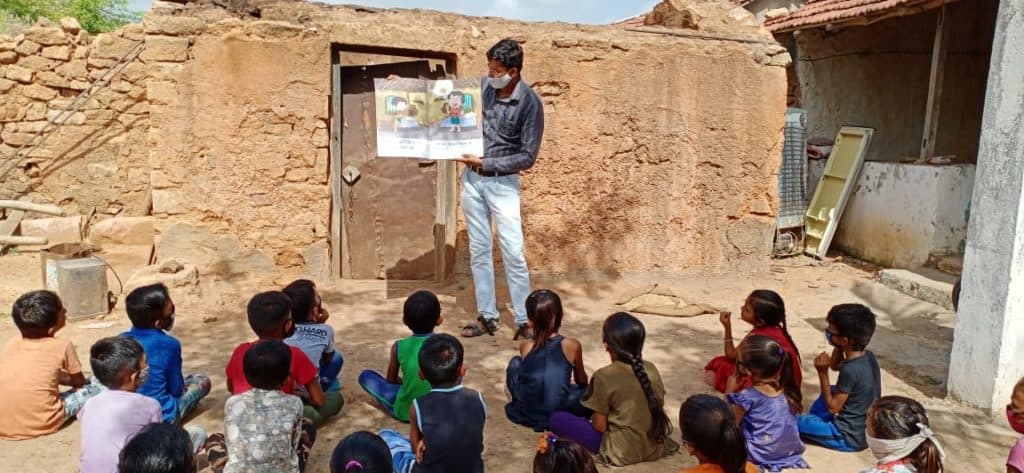

From temple premises to public gardens to open grounds and whatever open spaces were available in their areas, from terraces to atop stationary trucks to under the tree, government and municipal teachers took smart initiatives to try and ensure the continued education of these primary school children. They did this, even when they had to double up for election duty, COVID-19 surveys and now vaccination duty.

As many of these poor students could not access the internet, the state education department launched a Sheri Shikshan (street education) programme. Initiated first by the Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation towards the end of June when the COVID-19 curve started flattening, its success prompted the state government to implement it across Gujarat. The programme, essentially for poor students in primary school, took them back to studying outdoors with teachers conducting classes in open areas in and around their schools.

“On seeing a favourable response in Ahmedabad, we decided to implement it at other places too,” says former education minister Bhupendrasinh Chudasama. “Instead of students going to school, teachers are going to them.”

Under this initiative, students who could not attend classes virtually or were unable to catch up on their lessons due to varied reasons started learning outside the four walls of a classroom. Seeing students studying under trees, temple complexes, sheds, near farms, open lands, community centres or even in an open tractor-trolley during morning hours, became a common sight in Gujarat’s cities and adjoining districts.

In fact, this arrangement facilitated activities which were otherwise not possible in the traditional classroom setup. In fact, some schools have decided to continue the system even when normal classes resume.

Taking to the streets

Students of municipal schools in Ahmedabad faced the same problems. A majority of the parents of children studying in the city’s municipal schools are labourers and have only one smartphone.

Also, as schools shut operations, teachers were assigned different duties, such as surveys for COVID-19 and vaccination drives. Yet, they arranged for evening classes, which enabled children of working parents to study using the single smartphone available.

Rekha Garchar, a Math teacher for classes 6 to 8, from Kubernagar English school faced a tough time initially as the children did not understand the concept of online education.

“There were a total of 148 students in my school,” said Rekha. “I went to the homes of the majority of them and taught them to use phones. Since parents were not available during the daytime, I used to take classes in the evening for one hour from 7 pm.”

Read more: Delhi: Tepid response to reopening of schools as parents prefer to wait and watch

As most students, and parents, were not comfortable with virtual classes, Rekha decided to implement a hybrid model. “Along with regular online classes, I fixed weekends where I could meet them: at a temple in the area or some open place and solve their queries,” said Rekha. “All the while I was also conducting door-to-door survey work and vaccination work.”

Rekha also designed worksheets for assessment, where the children performed quite well. “It was a proud moment for me when parents of a student living in a hut in Kubernagar told me that he has asked his relatives to send their children to school as teachers were very good,” she said.

Jashodaben Bodar, a first class teacher in Muthiya Gujarati School faced an issue where the kids were attending school for the first time. “Online learning for such kids was a Herculean task and I did not know how to start,” said Jashodaben. “I decided to hold classes at a temple while complying with COVID-19 norms. The children did not know how to write and even identify letters. I had to teach through different mediums such as clay and sand. I got good results and slowly got them into online learning. There were 29 students in class 1 and 44 in class 2”.

Read more: Preschool closures in Delhi: Where will our toddlers learn when the pandemic is over?

Hitesh Shah, math and science teacher for classes six to eight at Sardarnagar School went to his students’ homes and took evening classes through different apps. For assessment, he conducted an online quiz. “I was born and brought up in a chawl,” said Shah. “I knew the problems and, I aimed to give proper education to children in slums and chawls so that they could learn well”.

“There were common problems like limited access to phones,” said Shah, “At times parents did not have money for recharge so children used to skip classes. In many cases I helped them financially also”.

And the students are enjoying this. For instance, we found the pupils of standard one at the Gowardhan party plot in Thaltej celebrating festivals associated with education. Like Guru Purnima, where they sought blessings from their teachers, sang rhymes, and took blessings from their parents.

“Children of this age group (in primary school) require an activity-based approach to learn basic concepts,” said Sarmishtha Patel, class-teacher of standard one, taking her class at an open plot of land. “Holding classes outdoors supports holistic development as we can use many aids such as flowers to count, draw on the ground, and much more. Kids also practice such learning at home and send us videos of them doing so.”

Saurashtra and Kutch

Similar scenes and sentiments could be seen and heard in other cities like Rajkot and Kutch.

A primary school teacher in Mandvi in the sprawling Kutch region converted a bicycle into an “e-bicycle” to travel to childrens’ homes in distant villages and teach them at home.

Deepak Mota, who teaches at Hundrai Bagh School in Mandvi, first used his car. He called it an “education chariot” but after the cyclone and heavy rains made the roads to remote villages inaccessible, he decided to convert his bicycle into a teaching platform. His cycle too has a USB charging point, battery indicator, a speedometer and space to put laptops and speakers. Mota says he spent Rs 18,000 to Rs 19,000 on this.

The decision to continue primary school education in open spaces has shown good response everywhere it is being tried out.

Aminaben Sama, principal of Metoda Prathmik Shala (primary school) of Rajkot faced a different kind of challenge while she started street education way back in July 2020.

“Our school was built in 1960 and was in such a dilapidated state that the entire structure had to be pulled down,” said Aminaben. But she is not unduly worried about this since her street school has 100% attendance. Aminaben had adopted street education since July 2020.

“During the first lockdown, we shifted our classes online through WhatsApp,” recalls Aminaben. “Later we adopted ‘Microsoft Teams’ mobile application for teaching.” But they also started the street school, which has 129 students from classes one to eight with six teachers, including the principal.

“Despite the non-existent ‘physical school building’, 25 private school students sought admission in our school last year and even in the current year,” says Aminaben.

Studying under the banyan tree!

Both students and teachers seemed quite happy learning and studying out in the open. Like Dhruvi Balwantbhai, a class two student at Mithyala Prathmik Shala. “I enjoy learning in this new set up,” she said. Her parents added, “We do not have to push her anymore to get ready for school. She is eager when it’s school time.”

Mithyala Prathmik Shala has 430 students and 12 teachers. For each standard, two hours of daily learning outdoors was organised.

“Holding classes outdoors is a far better concept as online education was unable to capture students’ attention and, only two to four students joined the class,” says Balvant Sankhad, Principal. “With classes being held out in the open, there was 80% attendance and, even teachers enjoyed teaching. Learning in an open environment interests students and enhances their grasping capabilities.”

“There was no guarantee whether kids were learning or not in the online medium,” said Arvind, a farmer who has two daughters studying in class one and three. “Street education has brought immense change, has redeveloped their interest in studies and as parents, we are happy that they are learning new things physically.”

According to Kiritsinh Parmar, Administrator, Municipal School Board, Rajkot, around 88 municipal schools in Rajkot have started educating 5166 students with the help of 665 teachers at 240 outdoor spaces. Many teachers now say they would like to continue this pattern of education even after conventional classes re-start.

Co-authored by Masuma Bharmal Jariwala, Neha Amin and Chhayal Bhatt (Development News Network, Gujarat)