An old saying goes “it is better to side with the devil you know than the devil you don’t”. To me that seems the only reason for Bengaluru’s voters resisting whatever wave swept the rest of the state. Only in Bengaluru did BJP retain the 2018 number of 16 seats, even as it got washed away everywhere else.

There are analyses aplenty in the media and the internet on how and why the BJP lost the state so badly. You can draw your own conclusions from them. Maybe India needs a new Long March revolution to get out of the mire it is stuck in. Because for me, the truism that “the more things change, the more they remain the same,” applies to Karnataka, irrespective of the poll results.

A different mindset

Here I am just trying to look at why Bengaluru bucked the trend. The start is with an important number, vote share, which overall across the state has remained about the same as in 2018 for the BJP. Only in Bengaluru has the BJP actually managed to marginally increase its vote share.

Is there a credible explanation for this curious anomaly? Let me try. Obviously, the average Bengaluru voter is not carried away by promises of freebies, like free rice and gas cylinders and changes in quota reservation in government jobs to certain sections. Even Congress’ promise of some sort of unemployment allowance to poor, unemployed graduate and diploma students, and allowance to women heads of poor households did not make them rush to the booths to vote for that party.

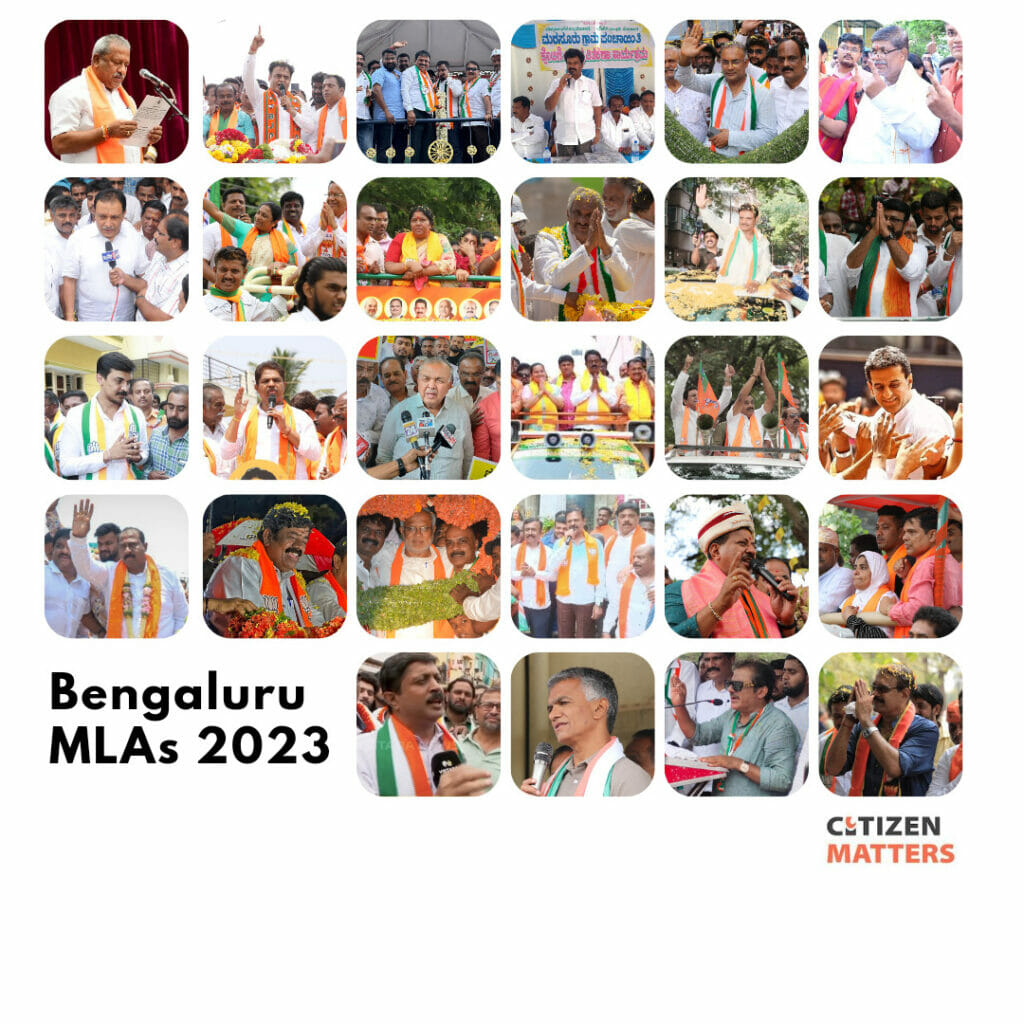

Read more: Bengaluru, meet your new MLAs, who are mostly old MLAs

Obviously there is a different mindset at work here that has created a somewhat symbiotic relationship with their sitting MLA. Could it be that the ‘quality of life’ factor resonates more with all classes of the city voter as compared to his peers elsewhere. Despite the fact that no party offered anything very specific for Bengaluru in terms of improving the quality of public services.

No doubt, each city MLA has a core support group in his constituency whom they are able to keep together and bring to the polling booths. No candidate bothered to woo any other kind of vote bloc. Especially the urban middle and upper income class bloc. Whatever anecdotal evidence I could get, from mainly among my many relatives, showed that they are staunchly with Modi. And are completely indifferent to all arguments that the BJP brand of politics is divisive and polarising.

Faith in the promises

They probably preferred Modi’s promises of aspirational projects on roads, luxury transport systems, IT hubs, AI research centres, and the other hi-tech, capital intensive promises made for the city. They are sure Modi will find the money for all this and it will all be to their advantage. So why bother voting for a particular state government.

A former colleague, who has been covering Karnataka and Bengaluru politics for years, had another intriguing explanation.

The phrase she used was “accommodative politics” among the city’s sitting MLAs and their rivals. A kind of you scratch my back, I scratch your’s arrangement. Especially when it comes to making money, any which way they can.

Such ‘accommodative politics’ is nothing new. It happens all the time in any election everywhere in certain segments and seats. With rivals putting up weak candidates in some seats to reap other benefits elsewhere. That an experienced journalist feels that is a factor in this city did come as a surprise, though.

Establishing a rapport

I do have a theory of my own too. I mention it here with some hesitation, though. Bengaluru has a number of citizen groups and activists working in diverse fields. And without an elected municipal council over the last three years, these groups have established a rapport, no matter how tenuous, with the sitting MLA, in their efforts to improve governance, especially at the ward level.

A new MLA would have meant starting the process all over again. So while they went on with their campaigns of creating voter guides, helping voters to get to know their candidates and urging more people to go out and vote, maybe, just maybe, they hoped that they could continue to work with the sitting MLA they knew rather than someone new they did not.