Is ‘culture’ and its representation through art galleries ‘public’? This question came to my mind when I recently dropped by the National Gallery of Modern Art (NGMA) Bengaluru after a gap of 6-7 months. When I attempted to walk in, a security guard stopped me at the gate, and asked me to buy a ticket.

Surprised, I enquired if the gallery had started charging a parking fee, and pointed out that I was on foot. He said, “No, no, it’s entry fee. Everyone entering the compound has to pay.” Though he replied promptly, he seemed a bit annoyed. Perhaps other visitors had asked him the same question.

I was taken aback. Since the national gallery had been set up under the aegis of the Ministry of Culture, Government of India, my understanding was that it was a public building, which meant one could enter it freely. Much like one could enter the premises of the City Central Library, High Court, or any government office for that matter.

Of course, once we enter the compound, we may be asked to pay a parking fee for our vehicles, or a visitor fee to access certain sections of the building. But being asked to pay right at the gate seemed unacceptable. Was this an attempt to boost the gallery’s revenue? Was it not making enough money? But should a national gallery or museum only be concerned about making money? Ultimately, whose ‘culture’ are they holding in trust? Ours.

While these thoughts were running in my mind, I bought the ticket because, after all, the guard was just doing his job. I then walked to the gallery shop/reception and asked about the ‘entry fee’. They said a circular had been issued about six months ago, asking the office to charge entry. I asked again if this was meant to be the parking fee, and if I would have to pay a separate gallery fee as well. And then they looked almost resigned; it was clear others had indeed asked the same question.

Earlier, those who wanted to see the collections had to buy a ticket at the reception, but all other parts of the 3.5-acre compound were freely accessible. I was told the ‘entry fee’ would be valid at the gallery too, but another question came to my mind – what if I had not come to see any of the exhibitions or paintings?

Can one not walk into ‘public’ museums or galleries otherwise? What if I had just walked in because it was a peaceful corner of the city, set amidst acres of greenery and mature trees? In fact, that was the reason I had walked in that day, without having planned to.

This may seem like a minor issue. After all, there was no harm in charging entry; it was only Rs 20. But what if I was a student who wanted to access the ‘public’ library and art resource centre on the first floor? Or someone who wanted to watch a film or listen to a talk at the auditorium, or just wanted to buy coffee at the café or some gifts from the gallery shop?

Is a national gallery not a public space?

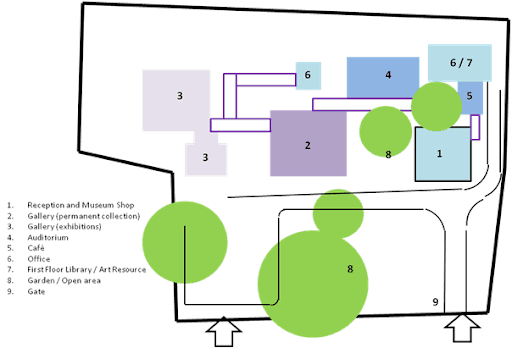

NGMA Bengaluru has many sections – galleries housing permanent collections, galleries for temporary exhibitions, an auditorium that can be hired for events, a cafeteria, a public art reference library and a museum shop; their words – not mine – from their website and annual reports. There’s also a nice garden in front, with a few trees that are over 100 years old, since some of the buildings were once part of a colonial-era bungalow. All these are spread across 3.5 acres of land.

Schematic sketch of the NGMA compound. Source: worldarchitecturenews.com

So the compound hosts multiple activities in a supposedly ‘public’ space. Then how could someone regulate access to that space? Aren’t national galleries and museums meant to be for everyone, much like public parks? This was, after all, not a private museum or collection that could gate-keep by charging a fee to enter its premises.

Besides, the city does not have too many public spaces, and now one more was being closed off. And no, the coffee shops and malls don’t really count. They aren’t really ‘public’, though we like to imagine them so. For that matter, everyone can actually walk into a mall; there’s no one charging an entry fee at the gate.

Who is a national gallery or museum for, then? Is it only meant to be an exclusive space for a particular set of people who can appreciate and enjoy ‘culture’? Or is it meant to be an inclusive space, one that makes an attempt to reach out to everyone, as it engages with ‘our’ culture?

Footfall is already low at NGMA

The decision to collect entry fee comes at a time when national museums and galleries worldwide are going the extra mile to increase footfall – to attract people in, not keep them out. A national museum in England has opened its central courtyard as a meeting place where people can ‘hang out’, while it efficiently controls access to the collections. The courtyard is open even when the galleries are not.

Another museum is throwing open its ground floor as a ‘street’, so that people can walk through it to access the adjacent river more easily. Previously, people south of the river had to walk around the long-ish building.

What makes the Culture Ministry’s decision seem more difficult to understand, is that its 2017-18 annual report records total visitor numbers at NGMA Bengaluru as 38,707. (The ministry’s annual reports are to be made available for ‘public’ scrutiny.) That’s probably just a regular weekend number in any of the city’s malls. In comparison, NGMA Delhi’s annual footfall for the same year is 80,862, and the Mumbai one’s is 46,690. (The Bengaluru and Mumbai galleries are under the jurisdiction of NGMA Delhi.)

The footfall at national museums were much higher. The National Museum, Delhi, recorded 2.25 lakh visitors, Victoria Memorial Hall in Calcutta 36 lakh visitors, and Salar Jung Museum, Hyderabad, had 12.5 lakh visitors.

Now let’s assume that each of the 38,707 people who visited NGMA Bengaluru that year paid Rs 20. Say, 1000 of them were children from school groups, who are exempted from paying the fee. The annual revenue through ticket sales would then be only Rs 7,74,140.

So, evidently the decision was not entirely about money, as the ticket revenue may barely cover the gallery’s annual utility bills or local taxes. Also, the visitor numbers indicate that charging entry fee is unlikely to result in a huge increase in revenue.

So what could the reason be? Maybe that NGMA was, to a very small extent, becoming ‘public’. Over time, I had observed students and employees from nearby spaces eat their packed lunches there and revelling in the fact that they could do so. But of course, this is entirely speculation.

I did read a small column though, which said some artists had protested when the fee began to be charged around last January, but that nothing came of it. I haven’t spoken to the artists and don’t know their reasons, but it appears they were concerned that a ‘national’ gallery was becoming even more exclusive than it already was. Shouldn’t the Ministry of Culture be addressing the serious problem of why culture is still inaccessible to most people?

No, instead it’s made the gallery more cumbersome for people to visit, almost impossible now for anyone who might accidentally read the sign ‘National Gallery’ and want to walk in. They and I would probably think, “Why pay Rs 20 when I don’t know what to expect inside…just old paintings that have nothing to do with me…”

Ironically, the 2017-18 annual report also includes a Citizen’s Charter, which says that part of the ministry’s mission is to implement sustainable solutions “… through which India’s diverse tangible and intangible culture and ancient heritage will remain universally accessible”!

I recently went to NGMA with a couple of friends who are foreigners and had to pay an entrance fee of Rs1000 for the two of them, the entrance fee for foreigners having been fixed at Rs 500. When the entrance fee for Indians is Rs20 charging 25 times for foreigners seems quite disproportionate.

Why Photography is not allowed. Every where in the world it is allowed.