On February 1st, union finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman presented the final (Interim) budget from the current government that will seek an electoral mandate in a few weeks from now. The minister’s speech had only two major announcements on urban public transport: one, that e-buses would be encouraged, and two, that Metro Rail and NaMo Bharat trains would be further supported in large cities. This followed the same pattern of allocation for transport that the union government has made over the five years of its current term.

Indian cities have been grappling to contain heavy traffic and emissions from the large volume of vehicles on the road. The need for sustainable and effective public transport cannot possibly be missed. Strangely though, potentially the most effective solution to this — well-connected city bus services — has received far less attention and funding than they deserve.

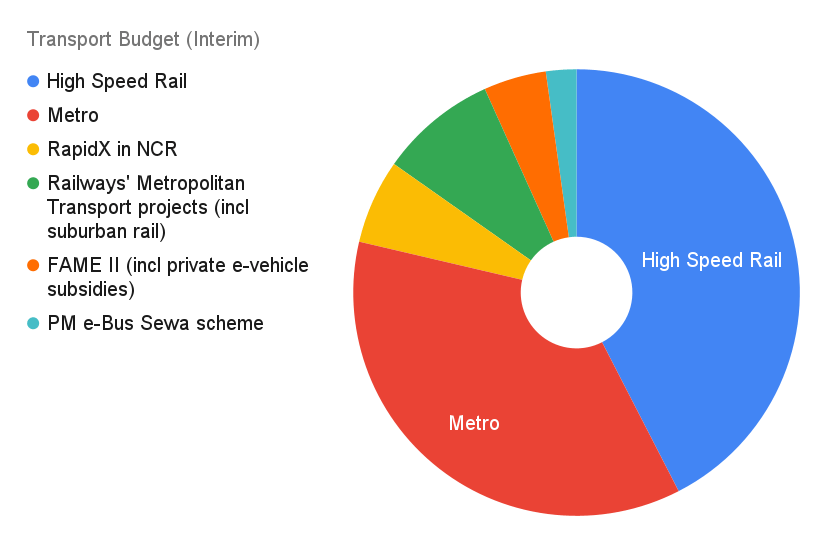

Instead, almost all of the funds for public transport projects have gone towards cost-intensive Metro and high speed rail projects, which, by design, can carry only limited populations over specific stretches. If city bus services got any attention in the budgets at all, it was only through the proposed introduction of a small percentage of e-buses into the existing network.

In the union government’s five-year term, Metro and high-speed rail (HSR) projects received an estimated funding of Rs 1.4 lakh crore. In comparison, the funds for urban bus transport was a measly Rs 4,048 cr over this period, an analysis of union budget documents show. That is, urban bus transport got only 3% of the funds allocated to Metro and HSR combined.

Proponents of sustainable transport have long argued that investing in buses is a much cheaper, quicker way to boost public transport adoption. Funding for suburban rail, which is also a cheaper, more popular transport mode, like buses, has been low as well.

Read more: The gaps in public transport that are pushing people towards private vehicles

Budget documents show that over the five years from 2019-20 to 2023-24, the Centre’s spending on Metro systems has remained high, and funding of HSR and rapid rail systems increased year on year. But the government promoted only two schemes for buses in the same period — FAME II (Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of (Hybrid and) Electric Vehicles II) and the PM e-Bus Sewa Scheme, both of which subsidise electric buses.

Trends: In five years, Rs 88,000 crore on Metro alone

In the four financial years from 2019-20 to 2022-23, the union government has spent nearly Rs 69,350 crore cumulatively on various Metro projects. In the ongoing 2023-24 FY, the estimated spending is Rs 19,508 crore, taking the total to around Rs 88,858 crore over the five-year term.

Among urban transport projects, the Centre’s second highest spending was on the National High Speed Rail Corporation Ltd (estimated at Rs 51,742 cr). The actual spending in the first four years was Rs 33,150 cr, and the estimated spend in the current financial year is Rs 18,592 cr.

The corporation is currently building its first HSR line — the Mumbai-Ahmedabad bullet train corridor. Though the project was supposed to have been completed in 2022, as of this January, only land acquisition was completed and all civil contracts awarded, and works were in progress.

The RapidX rapid rail transit system that will run Namo Bharat trains in the National Capital Region, is estimated to get a total funding of Rs 9,166 crore in the current term.

Big announcements on bus schemes, but low spending

In her 2021-22 budget speech, finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman had announced a new scheme costing Rs 18,000 crore, to deploy 20,000 city buses in the Public Private Partnership (PPP) model. However, no funds were allocated for this.

Only last August did the government launch the PM e-Bus Sewa scheme with an allocation of Rs 20,000 crore. The scheme is to run until 2037. But the number of buses to be subsidised under the scheme has been halved to 10,000 (from 20,000 announced previously).

Also, the current scheme is solely for electric buses, and not for city bus services in general as initially envisaged. Only Rs 20 crore is estimated to be spent on the project this financial year, and bus deployment has not yet started.

The scheme is intended for 169 cities, with priority for cities having no organised bus service. The Centre will provide a per-km subsidy for the bus’s operations, and the private vendor has to cover the remaining expense through ticket revenue. If the latter is not possible, the state government is obligated to bridge the gap so that the service can continue.

Are e-buses enough for our cities?

Ravi Gadepalli, public transport specialist and independent consultant, says this model addresses the issue of timely Viability Gap Funding (VGF) for bus services to ensure their sustainability. But he says the programme may not completely meet the current demand for urban bus services.

“The unmet demand for buses in cities is much higher than the current target of 10,000 buses planned under the scheme. The scheme can explore expanding its outlay and bus numbers by partnering with development financing institutions like the World Bank.”

Read more: Delhi electric vehicle policy: Ambitious targets, but is the capital ready?

The other e-bus scheme FAME II, implemented over this government’s five-year term, will provide for charging stations and a total of 7,210 e-buses at the cost of Rs 4,048 cr, as per a press release from the Heavy Industries ministry on February 9th. The scheme has exceeded its target of 7,090 e-buses, though the actual delivery of about half the buses is still in the pipeline.

Ranjit Gadgil, Programme Director at the Pune-based NGO Parisar that focuses on sustainable transport, says the urgent need is to augment regular city fleets at large, rather than focusing on the technology of these buses. “Except big metros like Bengaluru and Delhi, smaller cities don’t have the charging infrastructure or the technical capability to run e-buses. Such a city would not benefit from adding, say five e-buses, to its fleet,” he says.

Any investment in bus transport is green mobility irrespective of the technology used, he adds. “Pune, for example, has only around 2,000 buses, but 20 lakh private vehicles. The emission from private vehicles is a bigger concern than a few buses running on CNG. If passengers get sufficient, reliable bus services, they will switch from private vehicles to buses.”

SUM Net (Sustainable Urban Mobility Network) — a nationwide coalition that Parisara is part of — has been campaigning for a minimum of 50 buses per lakh population, a benchmark most Indian cities have not attained.

According to a 2023 paper from IIT-Delhi, titled ‘A framework for selecting an appropriate urban public transport system in Indian cities’, only Bengaluru, with 45 buses per lakh population, is close to meeting this goal. Several cities including Pune, Lucknow and Surat have fewer than 10 buses per lakh of population. Even metropolitan cities like Mumbai, Delhi, Chennai and Kolkata fall far short, with only 28, 22, 31 and 30 buses respectively per lakh of population.

An RTI response Ranjit got in 2020 also sheds light on the low priority for bus services. As per the response, in the five preceding years, the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs, which usually spends the most on urban transport projects, had spent only Rs 352 crore for urban bus procurement, versus Rs 74,402 crore for Metro rail construction.

The Ministry of Road Transport and Highways, with its primary focus on road infrastructure and national highways, also spends small amounts on a separate category named ‘Road Transport’ — with annual funds ranging from Rs 148 crore to Rs 273 crore the past five years — these funds go towards a multitude of components including VAHAN database and accident victim compensation. The category does include a couple of bus-related components such as Intelligent Transport System, but the amount spent on these is unavailable on the ministry website.

Suburban rail needs more funding

Despite the imperative in several cities to improve their suburban rail services, Indian Railways’ spending on its ‘Metropolitan Transportation Projects’ is estimated to be only Rs 9,147 crore over this government’s five-year term.

However, Railways has separately made high investments in Kolkata suburban rail, with an estimated additional spending of Rs 7,725 crore over five years. For Bengaluru suburban rail, spending has been low, at only Rs 50 crore until 2022-23. In the ongoing 2023-24 FY, estimated funding is Rs 450 crore.

Is investment going into the right areas?

While Metro is also green transport, experts say the problem is Metro projects being started in many small cities – for example, Nagpur and Kanpur – that have no demand for it.

A 2022 report by the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Housing and Urban Affairs itself had pointed out that except Delhi and Mumbai Line 1, all Metro projects in India are unable to meet their projected ridership demand. The report identified faults in the ridership projections in the Detailed Project Reports (DPR) of Metro projects. Hence, in smaller cities, it recommended implementing MetroLite and MetroNeo, which can be built at 25-40% of the cost of a regular Metro project.

Read more: How are India’s Metro Rail systems faring?

There are similar concerns about HSR projects too.

Ravi Gadepalli says that small cities can benefit from projects like BRT (Bus Rapid Transit) system or suburban rail, pointing to the example of the Hubli-Dharwad BRT that has a ridership of one lakh per day. These are lower-capital options that utilise existing infrastructure.

However, the local demand for suburban rail services in many cities often doesn’t translate into Indian Railways’ budget making process.

With respect to bus services, Ravi says that laws such as the Road Transport Corporations Act enable bus service provision but have limited focus on service obligations. “Internationally, this is being addressed through legislations, such as the Public Transport Service Obligations in Europe, that provide a framework for setting service obligations and commensurate funding for buses. Such legislative backing will go a long way in improving bus services in India.”

Common mobility cards still ineffective

The National Common Mobility Card (NCMC) that can be used across various transport modes like bus, Metro, suburban rail, etc., was announced way back in the 2019-20 budget. PM Modi had launched the card in 2019 as well.

Users would also be able to use the card to pay parking charges, toll tax, and even for retail shopping and cash withdrawal. Since NCMC would help travellers use the same card seamlessly for multiple transport modes, it was expected to attract more people to public transport.

Though NCMCs are available in several cities now, these cards largely work in Metro stations only, effectively making it yet another Metro card. Other transport modes, such as city buses, don’t have a system to read the cards. As per a report in The Print last October, Metro rail corporations in only six cities, and bus transport systems in three states, had implemented NCMC until then. At the time, Mumbai was the only city where the card could be used in both Metro and buses, but it couldn’t be used in the suburban rail there.

Overall therefore, the government, in the second term of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, has continued to invest heavily in big ticket Metro and high-speed rail projects. Though the government’s e-bus programmes got much attention, these have not kept pace with cities’ actual bus requirements.

Campaigns for sustainable transport

Several cities have ongoing campaigns that seek to give a push to sustainable mobility. You too can be a part of any of these:

- Bus Hai Toh Delhi Mast Hai, Delhi: Greenpeace India launched this campaign two years ago by setting up the Public Transport Forum Delhi, a collective of 20 organisations, transport experts and ordinary citizens. The forum understands the bus transport needs of various categories of commuters – for eg., domestic workers – and lobbies with authorities to meet this. Those interested in volunteering can sign up on the website, email or connect on Instagram.

- #AppKaraBusKara, Pune**: A campaign by the NGO Parisar, demanding that the Pune municipal corporation deploy the long-awaited comprehensive bus app for the city. Campaigners will install interactive prototypes of the app at five depots, which citizens can use to plan their journey and also fill in demand cards that will be addressed to the municipal administration.

- Walking Project, Mumbai: This campaign to improve Mumbai’s pedestrian infrastructure started in 2012. It primarily works as a watchdog to monitor the Mumbai city corporation’s works related to pedestrian infrastructure, says founder Rishi Aggarwal. To volunteer or donate, you can reach the team at X.com.

- Even smaller cities are now seeing campaigns for sustainable transport. For example, Ramgarh in Jharkhand, saw a campaign in 2019-2020 to make a 1-km stretch of road ‘smart’, with footpaths and cycle tracks. Residents and other civil society members worked with the local authority, the Cantonment Board, to develop the final road plan, but the project has not taken off due to fund shortage, says Basant Hetamsaria who led the campaign.

Is there a campaign for more sustainable commute options in your city? Would you like to start one? Comment below, or tell us more by writing to edit@citizenmatters.in

**Errata: The link to the #AppKaraBusKara campaign as first published here has been since updated with the correct one.