In the first week of December 2023, residents of Chennai and surrounding areas experienced flood fury, which brought the city to a grinding halt. When the 2015 Chennai floods happened, the authorities said it was a one-in-100-years disaster and would not occur for a long period. Yet, in eight years, here we are facing the consequences of a disaster.

Now the citizens are asking — who is to blame for the Chennai floods?

Major rivers, lakes and canals in the city come under the purview of the Water Resources Department. “But the department, which should be restoring waterbodies and channels in the city, is not at all transparent in its operations. Meanwhile, the Revenue and Registration departments, which have no business in the water bodies, have been making illegal pattas and registrations for the water bodies,” reveals the citizen audit conducted by Makkal Medai Platform.

The Citizen’s platform — Makkal Medai, which was earlier formed by many citizens groups including Arappor Iyakkam to look into the reasons behind the 2015 floods, came together again in mid-December last year to brainstorm on what citizens need to do to prevent future floods. As a first step towards active engagement with urban development policies and practices, a field-based citizen audit was done across the city by the members of Makkal Medai. The audit report was released on February 4 during the Kelu Chennai Kelu protest at Valluvar Kottam.

Reasons for the 2023 Chennai floods

The citizen audit highlights key issues for flooding in 20 areas in Chennai and provides recommendations to resolve them with local knowledge. These include encroachment of water bodies by both government and private buildings, increased road height, dysfunctional stormwater drains, lack of desilting and garbage dumped in water bodies.

Here are some key area-specific issues require government’s attention—

Perumbakkam and surrounding areas

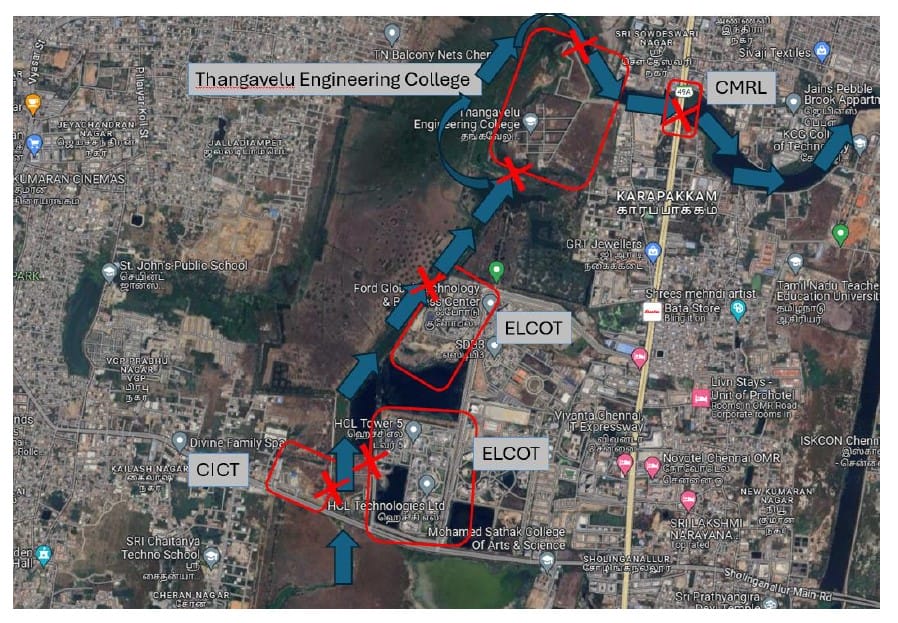

The total area of Pallikaranai marshland is shrinking due to encroachments. Institutional constructions like ELCOT, Central Institute of Classical Tamil (CICT) and Thangavelu Engineering College are major obstacles for the water from the south side of the Pallikaranai marshland to drain into Buckingham Canal through Okkiyam Maduvu.

One of the reasons for flooding in Perumbakkam is the poorly maintained Perumbakkam Lake. Sewage water flows into the lake, and the lake surface is full of hyacinths.

Manali-Sadayankuppam, Zone 2 Ward 16

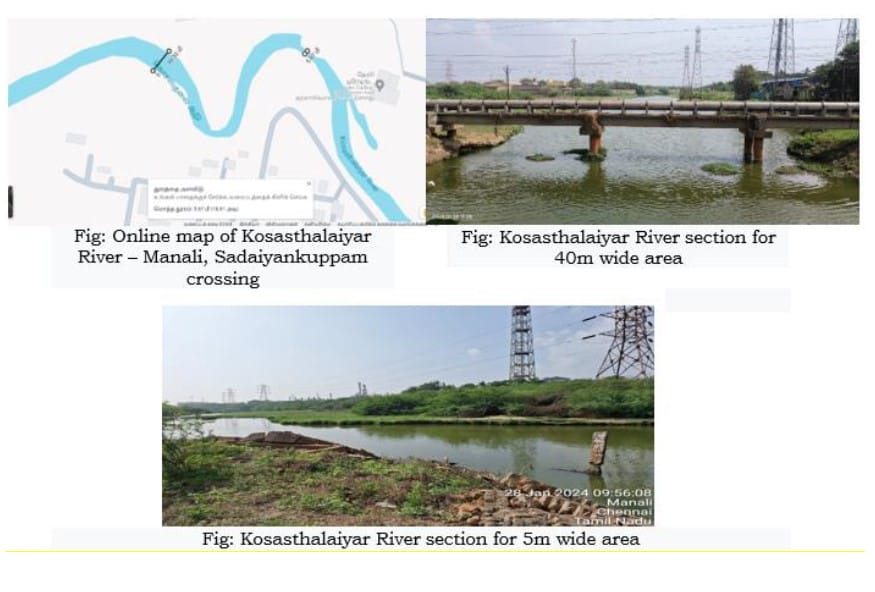

In Sadayankuppam – Burma Nagar Main Road, there were more than nine canals, which were the waterways for rainwater to reach the Kosasthalaiyar River. However, now only one canal remains functional, and another one is barely surviving.

Vyasarpadi Zone 4, Ward 46

- Water from MKB Nagar and Sathyamoorthy Nagar flows into Mullai Nagar, MGR Nagar, and JJ Nagar flooding these parts; a portion of the rainwater should be directed towards Captain Cotton Canal, while another portion should flow into the Buckingham Canal. There is currently no adequate pathway for the rainwater from these areas to reach the Buckingham Canal.

- The incomplete construction of the walls surrounding Captain Cotton Canal has led to water spilling over into residential areas. Just before reaching the Buckingham Canal, the Captain Cotton Canal narrows significantly, appearing clogged with construction debris. This issue requires investigation and remediation.

Otteri Nalla Canal

During the rainy season, the Otteri Nalla Canal overflows, causing flood water from Purasavakkam, Vepery and Choolai to accumulate in Govindapuram and Narasinga Perumal Koil Street. This indicates the carrying capacity of Otteri Nalla is not sufficient, which leads to floods in the low-lying areas of Choolai. The stormwater drain is of no use as it cannot drain the water into the overflowing Otteri Nalla Canal.

Read more: Saving Otteri Nullah: Desilting alone may not hold the key

Ambattur Estate Flooding

- Ambattur Lake is the second-largest lake in Chennai. It spans an area of 400 acres. Originally, this lake covered an area of over 1,000 acres, but due to the construction of buildings by the Housing Board, it has shrunk to its current size of 400 acres.

- The excess water from Ambattur Lake, through the drainage channel, passes through Ambattur Estate and Pattaravakkam and reaches Korattur Lake and the Lucas TVS channel. Due to the National Green Tribunal’s order to not release wastewater into Korattur Lake, the wastewater from areas like Ambattur, Ambattur Estate, Pattaravakkam, and surrounding regions, is accumulated throughout the year in the Ambattur SIDCO canal. Since 2015, whenever there is heavy rainfall all these areas get flooded as water cannot flow into Korattur Lake.

Korattur

When converting the Lucas TVS canal into a concrete canal, its width was reduced at the primary section and further narrowed down to ten feet, obstructing the path under a 200-foot bridge. This short-sighted decision has transformed Korattur into a flood zone. If the canal’s width had been maintained, the surrounding areas wouldn’t have been affected by floods as the rainwater would have been efficiently channeled.

Velachery

- The original expanse of Velachery Lake was about 255 acres, which has now shrunk to 55 acres. The other half of the lake, across the 100 Feet Road in Velachery, has disappeared, and work is ongoing to convert the lake’s channel into a covered canal. Covered canals are visible in various parts of Chennai, but it’s unclear how the municipality plans to maintain them. Approximately half of the 2 km long channel of Velachery Lake is filled with debris and wastewater. This raises questions about how flood waters will be managed.

- If the 300-acre garbage dump in Pallikaranai marshland were absent, the marsh could absorb the water, reducing flood impact.

Read more: Urban floods: Why some areas in Chennai are worse hit than others

Recommendations to prevent Chennai floods

- Implement effective solid and liquid waste management across the city, to prevent flooding.

- Conduct a comprehensive survey of the entire catchment area of the canals in Chennai including rainfall levels and prepare detailed plans.

- Correct the gradient of the drain. The existing drains with the wrong gradient are useless.

- Implement rainwater harvesting measures on roads in the catchment areas of water bodies to maximise water collection.

The Citizen audit report, that has area-specific recommendations, can be accessed here.

A call to action for the government to prevent flooding in Chennai

The Revenue and Registration departments should cancel illegal pattas handed over in marshland and other areas over the last few years and make officials concerned, accountable for illegal pattas and registration.

Chennai Corporation, Tambaram Corporation and other local bodies must ensure that missing links of stormwater drains and the capacity of the drains mentioned in the report are corrected. Lakes falling under these local bodies should be restored to their original capacity.

CMDA should avoid reclassification of water bodies and prevent change in ownership of waterbodies to favour private players/government. It should play a key role in restoring the Pallikaranai marshlands by putting a complete halt to construction activities in the marshland and reclassifying all available vacant lands of the marsh to water body immediately.

CMWSSB should stop letting sewage into the water bodies and build sufficient capacity for the treatment of wastewater. All Government departments must put a full stop to legalised encroachments by their own departments in water bodies such as Pallavaram Putheri and other places.

The Government must learn lessons from 2015 and 2023, take the recommendations from this report seriously and work towards restoring Chennai!