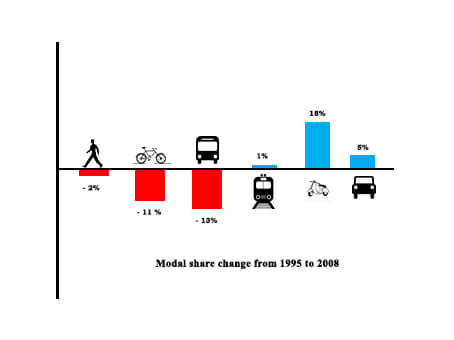

It is a truth universally acknowledged that public transit in Chennai is fragmented, poor in service quality, and dying a slow death in the last two decades. Certainly, the patronage numbers of the Metropolitan Transport Corporation (MTC) and other modes of public transport would support this with modal share dropping over the last few decades, concomitant with an increase in the modal share of private vehicles.

The experiential knowledge of service quality is that service frequency, in particular of the MTC buses is poor and unpredictable; buses and trains are often crowded, and signage and information on fares and routes and timings are patchy at best.

Switching from one mode to another requires much patience, time, keen observational skills, and dogged perseverance. The Institute for Transportation and Development Policy (ITDP) highlights how as a result of this poor service quality, commuting has become more complex, frustrating, and uncomfortable.

G. Ananthakrishnan, formerly a senior editor at The Hindu, and a public transit buff, has pointed out that MTC’s information systems are poor, even downright misleading.

Every now and then there will be grand announcements of interlinking of services – suburban train, MTC, Metro; of forming an overarching authority for transport in Chennai; of having real-time tracking of buses; and of course development of an app. Hearing all this, and experiencing the perils of using public transport in Chennai as a person of privilege, I wonder how come then people without all the advantages I take for granted, manage to navigate public transport on a daily basis?

Recently, we at the Citizen consumer and civic Action Group (CAG), decided to look at one aspect of this behemoth which is public transport in the city.

We asked, how do commuters obtain and process the information on services? Is the information easily accessible, understandable, and adequate? And how do commuters interact with the service provider – do they know about grievance redressal mechanisms, or are there any processes for users to input on planning?

We interviewed 506 public transport users, ensuring variation in age groups, gender, and socio-economics. This is a small number compared to the public transport users in the city but it provided an interesting snapshot.

Public transport services turn to apps

Traditionally, information has been disseminated through multiple modes – bus numbers are painted on bus stops; signboards on buses give the bus number and route (in English and Tamil); on trains too there are LED boards; timetables are posted at the ticket counter, and sometimes announcements are made on board. In buses that depends on the bus conductor who might shout out the stop or not. At bus depots and train stations too, these announcements on the next service are made.

While these continue, in recent times websites and mobile applications or apps have become ‘the thing’. Pre-Covid, MTC used to have quarterly meetings with consumer groups to gain feedback and at these meetings when faced with questions about poor information systems, MTC would relay the same response, “We are developing an app which will give all the information a commuter needs”.

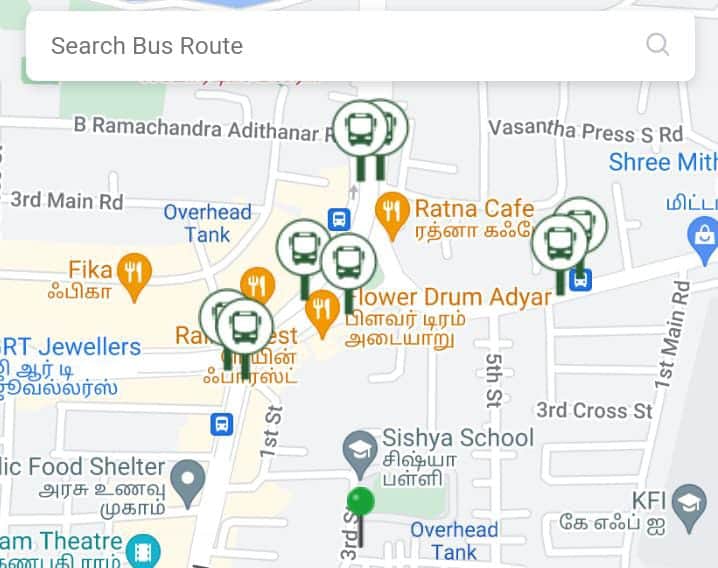

Last month, MTC finally launched the app – Chennai Bus. The Metro and MRTS already have their own apps. Some even have digital ticketing. To make things more confusing, there are also private apps like Chalo, Where is my train?, and Moovit, which also provide similar information to the commuters.

With such a surfeit of options in just apps, we thought we’d find a lot of smart young people of the city happily jumping on the app bandwagon. Of the 506 people, only 38 used the internet for information on transit. The go-to option was to Google search (20 people); 9 people used Where is my train? (a Google app); 5 Chalo; 2 Ixigo; 1 Chennai Metro app; 1 suburban rail app; and 1 Yo Metro. A few people said they used an app in addition to Google search.

So in reality, only 19 people used a transit app. (Caveat: This study was conducted before MTC launched its Chennai Bus app). We searched these apps on Google Play Store and realised it’s hard to tell which is a good one, or even which is the official app of the service provider.

The number of downloads for the apps we discussed earlier supports the suggestion that people are not getting app happy. Chennai Metro’s app was released in 2017 and has over 1 lakh downloads; Chalo (functions in several cities; we couldn’t find the release date) has over 50 lakh downloads; and MTC’s Chennai Bus (June 2022) has over 1 lakh downloads.

Read more: GPS speakers, panic buttons, pink buses and more: What the MTC rider in Chennai can look forward to

Perhaps commuters too are confused or perhaps even unaware of the existence of apps. Perhaps commuters too rely on friends and family or random conversations to stumble across apps? Certainly, of the 506 interviewees, the overwhelming majority said they rely on family/friends and fellow passengers for information so perhaps the same is true for information on apps.

So should service providers ditch the app route and stay old school? Not necessarily. CAG’s study found that while income did not impact access to smartphones or comfort level in using the same, education was linked to the comfort level in using smartphones. Age too was another factor – older people predominantly were not as comfortable with smartphones. So transport providers shouldn’t get hung up on one or the other but look to fine-tune and improve multiple modes of communication. Ultimately, public transport needs to cater to a varied user base and must bring more people into its fold.

Quality of information on public transport

While the information on app usage was not very surprising, the response to our questions on the quality of information had some surprises in store. We had asked if the information obtained from whatever source was adequate for a comfortable journey with no hiccups. Almost all (489 of 506) said yes, it was.

Pondering this, we realised that 325 (64%) were getting information from friends/family and other passengers while only 50 people (less than 10%) were approaching the service provider (ticket counters, bus conductors). So clearly information from friends/family or fellow passengers is providing greater value and/or is easier to access than that from a service provider.

Or perhaps people are so used to navigating our labyrinth systems on the fly that they don’t expect quality information systems from the service providers. In hindsight, more granularity on the question, such as asking why they prefer a particular source of information, might have been useful too.

Grievance redressal

We had also asked if commuters had engaged in any grievance redressal mechanism or deeper engagement in transport planning with service providers. While most people said their grievances were around high fares, service frequency and crowding, and that they had sometimes complained, we got the sense that there had not been much follow-up either by the service provider or the complainant. However, quite a few people said they would be happy if a mechanism to engage meaningfully with service providers was set up.

Modal shift from public transport

We were curious to know if commuters had seriously contemplated or were contemplating switching to private transport given the complaints about crowding, service frequency, etc. The nays had it with 335 people saying they felt public transport was adequate for their needs and that private transport was not affordable for them. Some mentioned that they did not know how to drive. One person noted that the bus was convenient to catch up on sleep!

When we looked at who said yes and who said no, by income and age groups, a pattern emerged. Across all income groups, it was the young working people in their 20s who said they would switch to private transport. Older respondents tended to say they would not be making that move. Those who use public transport, likely don’t see any other easy cost-effective options but those who can ‘afford’ a two-wheeler or car will move on. There is also an aspirational aspect to owning a two-wheeler and then a car.

Read more: Chennai Metro: Future of public transport or white elephant?

Bolstering communication on services

The Government of Tamil Nadu’s Transport Policy Note 2022-23 talks of alignment with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and that it envisions the future of bus transport in the state in terms of making buses user-friendly, affordable, efficient, with good last mile connectivity, accessibility for all, safe, using Intelligent Transport Systems (ITS), and finally shifting to cleaner fuels – all by 2030.

Commendable indeed and here’s hoping the state moves forward in leaps and bounds. In the process, the state should evaluate its current mechanisms of interaction with users of public transport. Communication cannot be a one-way street.

While the state must provide comprehensive, easy-to-access and use information in multiple modes, it must also strengthen systems for users to provide feedback and engage in transport planning and decision making. This will not only help the public transport network be more robust, but it will also aid in bringing in new users.

A first step would be to understand the user profile of each public transport mode, set up various ways for feedback, and do this on an ongoing basis – not once in a blue moon.

[This post was first published in the blogs of Citizen consumer and civic Action Group (CAG) and can be read here. It has been republished with minimal edits.]