In a recent online talk, Sidharth Bhatia, founder editor of The Wire, took us on a tour of the street that introduced public dining to the city of Bombay.

Shortly after sunset, author Bhatia began to unravel the colourful history of Churchgate Street, which now goes by the name of Veer Nariman Road in honour of lawyer-activist Khurshed Framji Nariman (1883-1948) who later became the mayor of Mumbai . “Bombay is a city of full-time nostalgists. History buffs concentrate too much on colonial Bombay, especially the 19th century. What fascinates me is the mid-20th century, and that’s what I’m going to share with you today,” he said.

The talk, titled “Food and Music on Churchgate Street: Bombay in the 1930s-1950s” was hosted by the Bombay Local History Society.

Bombay’s elite dining rooms

Drawing on visual memorabilia from private collections, he transported the listeners to a bygone era when new restaurants were opening up “on the road that links Marine Drive with Horniman Circle” in the late 1930s, 1940s and 1950s.

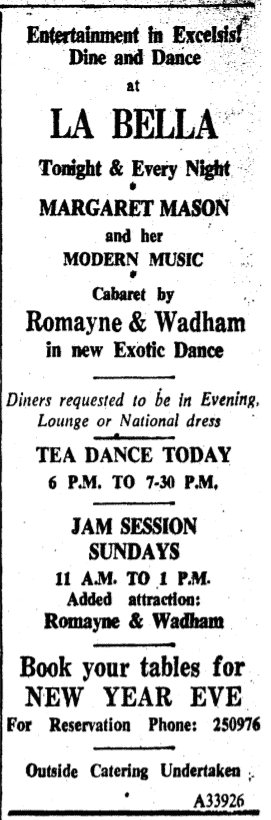

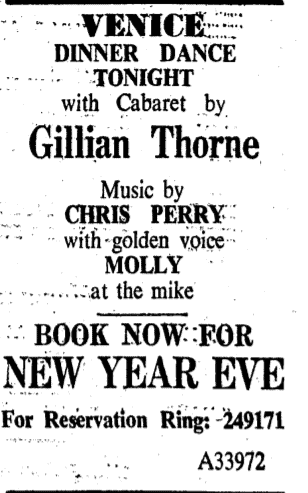

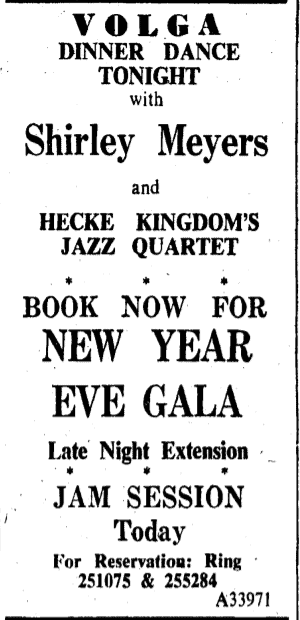

The names of these establishments built on land reclaimed from the sea — Gourdon & Company, Volga, Bombelli’s, Venice, Gaylord, Kamling and La Bella – conjure up images of Bombay’s elite warming up to the charms of fine dining, jazz and cabaret.

Bhatia grew up hearing stories of La Bella from his father, as he recounts in an essay titled “Jazz on Churchgate Street” (2015) written for Livemint. When his father “arrived in Bombay from Karachi via Delhi” he got a job at Hotel Astoria, followed by La Bella where he became the manager. His recollections of those “glamour-filled nights” were graced by fashionably dressed “industrialists, socialites and film stars like Raj Kapoor and Dilip Kumar” out to have a good time.

In his talk, Bhatia emphasized that these new avenues for leisure and entertainment marked the arrival of “a lifestyle and value system” that was “modern in character.”

The patrons of these restaurants were people “who liked what the West had to offer.”

Bombay, in their imagination, was not just an Indian city but also a city to be celebrated in the same breath as New York, London, Miami, Paris, Shanghai, Beirut, Cairo and Hong Kong.

Introducing ‘Conti food’

These restaurants trained their tastebuds to relish the continental cuisine on offer. Bhatia said, “What came to be called ‘conti food’ was a mishmash of styles, mainly dishes that were popular in clubs abroad. Many of them have completely? completed disappeared from the restaurants that we have today.”

Some of the favourites back then were Chicken a la Kiev, Prawn Cocktails, Lobster Thermidor, Steak Diane, Russian Salad and Minestrone Soup. They were served with mashed potatoes.

Cosmopolitan and proud?

Frank F. Conlon’s chapter titled “Dining Out in Bombay,” which is part of Carol A. Breckenridge’s edited volume Consuming Modernity: Public Culture in a South Asian World (1995), offers a useful background to understanding the period Bhatia spoke of.

Public dining was not unknown to residents of Bombay prior to the restaurants that emerged on Churchgate Street. However, the eating houses that existed were organized mainly along the lines of religion, caste and region.

The eating house was called a khanaval, bhatiyarkhana or jevanaval.

“The migration of male labourers to Bombay attracted from their villages and towns by the employment prospects in the city’s growing industrial and commercial activity guaranteed a continuing demand for a means of providing suitable, inexpensive meals within religiously and regionally specific diets such as South Indian Brahman, Gujarati Hindu, Sindhi Muslim, Maharashtrian Brahman, or Maratha,” writes Conlon.

Today, the word ‘cosmopolitan’ is used to indicate a broad-minded outlook that embraces diversity but it was employed in a pejorative sense in those times.

Restaurants such as those on Churchgate Street were dismissed as cosmopolitan because public dining in them was open to people of all religions and castes as long as they could pay to enter.

Elite dining joints

During his talk, Bhatia said, “Going out was a formal affair in those days. You had to make reservations in advance. If you wore jeans, they would sniff at you.”

Men who wanted to spend their evening at these restaurants were required to wear suits and bow ties, and women usually wore saris.

Even today, several clubs and restaurants turn away people who are not dressed in attire that is considered appropriate. The rules are often unwritten, and are particularly meant to exclude people from oppressed castes as well as queer and transgender people.

The pleasures available in the fancy restaurants of Churchgate Street were out of reach not only for this working-class demographic but also for middle-class families that rarely went out to a restaurant “specifically for the purpose of taking a meal and perhaps enjoying the ambience.” This held true even into the 1930s, as Conlon observes.

Refreshment rooms at railway stations and Irani cafés created opportunities for people to go out and eat at prices that they could afford, if not regularly at least on special occasions.

In a densely populated city with cramped housing, these places offered a few moments of respite and novelty.

More than just food

The restaurants on Churchgate Street, however, had more to offer. Bhatia spoke of jazz bands, magicians and ventriloquists that made each meal a memorable experience. “At times, they would have an emcee telling jokes –- a sort of stand-up comedian. Students from Government Law College, K C College, Jaihind College, Sydenham College and St. Xavier’s College would throng to these places. Once, the principal of Elphinstone College came and caught students by their ears,” he said.

Conlon reminds us of jukeboxes playing film songs, and family cabins –- “wooden and translucent-glass partitioned areas where genteel, respectable groups could dine without being exposed to public gaze.”

Bhatia said “these watering holes” , mostly run by expatriates, had a large following among people who came for the music bands and the cabaret artists but the consumption of alcohol was restricted thanks to Morarji Desai.

Before Independence, Desai served as the Home Minister of Bombay State, and he was later elected as Chief Minister in 1952. Bhatia said, “Because of the Bombay Prohibition Act, liquor permits were necessary. Of course, you could get alcohol for medical reasons, so people began to fake illnesses. The more adventurous restaurants served alcohol in tea cups.”

The talk was enthusiastically received by audience members who used shared reminiscences and anecdotes.

In these times of physical distancing, Bhatia’s conversational tone and evocative storytelling took people on a heritage tour of the city from the safe confines of their homes.

Some of these places do not exist any longer but they occupy a significant place in the hearts and minds of people who have seen them buzzing with life and activity.