Delhi 6, or Old Delhi, is famous for its street food. And every foodie who visits stops at Ashok Chat Corner, at the corner of Chowk Hauz Qazi. But while ordering their pick, customers often ask the man making the chats about the downed shutter in the tiny shop next door. “He has stopped coming,” the chatwala would reply. “He will be at home, it is just a few minutes’ walk. Take the straight road…..”, and would give directions to the home of Satya Narain Saxena – 2983, the tenth generation of a family of deed writers, today the last surviving document writer of Delhi.

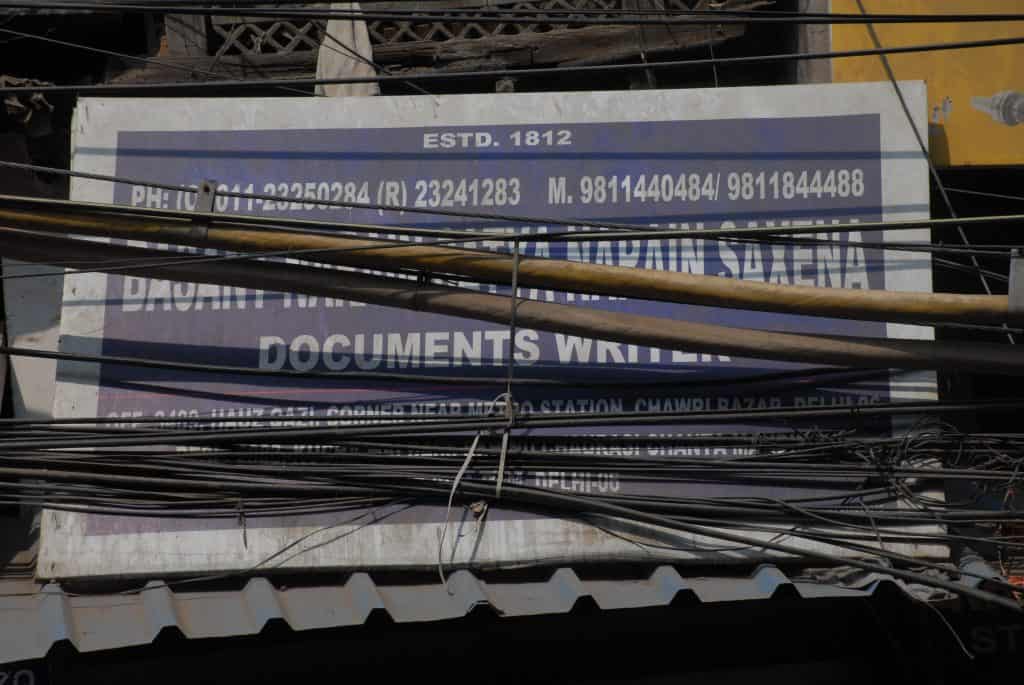

The chatwala would also suggest that they could call him. A newly painted blue and white board struggling for visibility through the jumble of hanging electrical wires, gives the details: Established in 1812, full name BASANT NARAIN SATYA NARAIN SAXENA, telephone numbers of all family members, address including the nearest landmark—the ChawriBazar metro station.

Turning left behind the Chaurasi Ghantewala Mandir, one walks into a maze of narrow lanes, choked with houses not numbered in any order. Ask for the location of 2983. Pat comes the reply, Saxena ji? And chances are you will be escorted to Saxena’s doorstep.

Bespectacled and on the wrong side of 85, Saxena is shrunk with age and infirmity. However, he appears dressed to meet visitors with visible joy, any time of the day. His wife points out that since he is not well and finds it painful to remain seated in the “shop”, he has shut it down. “A fire destroyed everything there,” said Saxena. “My sons had it renovated. But now what is the point in going there?”

The tiny house with a court yard in the centre, has been painted afresh; the room we are seated in is his grand daughters’— birds and flowers are painted on the pink wall. “It is khandani work that has been coming down the family, I am the tenth generation. Our ‘Kalam’ (Work/trade) is known as ‘Munshiji’. I am a Munshi. Ask for Munshiji anywhere in the city and you be will directed to me. Because now in the whole of Delhi, I am the only surviving Munshi. All my Sangi Sathis (friends and contemporaries) have gone.”

A bit of history

Saxena proudly shares his family history that goes back to the times of Moghul emperor Shah Jahan. His ancestors were, he says, part of Maharaja Jai Singh’s court in Amer. When Shah Jahan in 1639 requested the royals of what is now Rajasthan for the services of document writers, the king sent three of them, and the Bharatpur Raja sent as many. So they moved from Jaipur to Agra and then to the Red Fort in Delhi to be munshis in Emperor Shah Jahan’s court. “When the Brits took over, my ancestors made the nearby Chawri Bazar’s Bazar Seetharam both home and shop,” said Saxena.

The document writer regales visitors with stories that intertwine his family’s history and the history of India. One such story he tells: Emperor Akbar once anxiously told his “Nine Ratnas” that nobody bothers about the law and asked Birbal why that was so. Birbal had no reply. Neither did the others. The next day the gems went to Akbar and Birbal took out a piece of paper from his pocket and showed it to Akbar, who looked at it and said, ‘Who will understand the meaning of this? You know that I have gone to the Madrasa up to class 3’. Birbal then said: “Huzoor, the fact is that your Farman cannot be understood by the people. And if they don’t understand then how will they obey the law? Akbar asks Birbal to find a solution for this. Raja Todarmal, also one of the nine Ratnas asked for three months to do this.

“That’s how the process of documentation was begun by people like us. Then documents were written in Urdu, the emperor’s mother tongue, but they were also written in Arabic and Persian. All official work was done in these three languages, even now they are. Most words in the Hindi that you and I speak today have Urdu and Arabic as their origin,” says Saxena, returning to the present. He emphasizes that using Urdu was not a Mughal diktat, but the idea of Raja Todar Mal.

Saxena believes most of the deeds and documents, painstakingly handwritten in Urdu, Persian or Arabic, “like the calligraphy art you see in the mosques and forts,” is still alive in the system. “When the police lodge FIRs, or a patwari writes a document on a property, even if written in Hindi or English, many words are still written in Urdu, or Persian. It’s a court language that has not gone away yet, and is very reliable. There are no two meanings in what we write, no doubt or confusion. For instance, the word uncle means many things, even the man on the road is an uncle. But foofah means your bua‘s husband, no one else.” He ends every little story he tells with the question “Am I right?”

Saxena wrote or typed documents in Hindi or English. The documents were rent deeds, Kirayanamas and promissory notes, which are valid for three years, detailing the terms of repaying loan and interest, and are called “rehen Nama”, besides gift deeds, sale deeds, vaseeyat or will, and many, many more.

Even if he did not write the entire range of legal documents, he did quite a variety. His mind was the computer that had a proforma for every kind of deed and document. “I knew the language by heart for every kind of document that was required. My documents have never been challenged in the court. Only twice in the more than 70 years that I have been working, have I had to go to the court as witness,” he says with pride.

Grandpa sets up shop

By the time Satya Narain started writing, they were in “the shop” where his grandfather had been working from British times. He started sitting in the shop in 1950. His grandfather would say ‘come on pick up the Kalam, Dava and takhti (holder, ink and wooden slate). Satya Narain did not learn any of the languages, Urdu, Arbi, Farsi, in a classroom. Now, even the memories on paper and photographs have been reduced to ashes, literally, when the shop was gutted five years ago. There were yellowed, fading group photographs of his family while some papers kept at home were attacked by termite or chewed up by rats, said his wife Saroj Saxena.

Saxena said there used to be about 45 document writers in the capital at that time and they used to meet under the umbrella of Delhi State Wasiqanaweesan Association., Before the shop was gutted, his prized possession was a yellowed, fading group photograph of them and a few Urdu documents displayed for their sheer beauty. There were people who wanted to buy the ancient papers, but for him it was evidence of his lineage, something he would not part with. “We were so tied to that language, the munshiana zabaan, that there was no question of my wanting to do anything else”.

Each document writer of the old days had a dedicated clientele. Many clients even left the documents with the writers for safekeeping and would come for whatever was needed, whenever it was needed. “This was particularly true of the Mohammadens. I have asked them many times how long they expect me to be alive, and they would say you are going nowhere. Many papers have now crumbled to dust. Some young people come saying their Abbaji told them to come to me when there was a problem with legal documents. As if I will always be alive?”

Post the fire, the old, yellowed and patchy board proclaiming “Deed Writer “in English and Urdu was gone, and the blue and white one came up. After the shop was renovated, he would come daily, sit, and go back. There was no work.

The decline of document writing began with the arrival of the computer almost 25 years ago. And when the Internet came, it declined further, with the proformas available even on your phone. And it died when the government introduced e-stamp paper. That according to Saxena is the story of the decline and downfall of his profession. Death by digitization.

“So what work is left for me? A bit of translation sometimes. There is no work and no money. I don’t know computers.” His son Sachin is an exporter. Saxena told him not to think of becoming a document writer. “There is no one to carry forward his work,” says Saroj with a sigh.

| Tailpiece: A Google search for “legal documents in India” returned 46,50,00000 results. One website (www.pathlegal.in) lists “Agreements” under 16 broad heads. One of them pertains to gifting, wherein the proforma of 33 different files was followed by a “search to find more files”. There were 11 files and a “search to find more files” under the section called “Family settlement”. A section titled “Partition” pertains to the division of property over 15 files. |