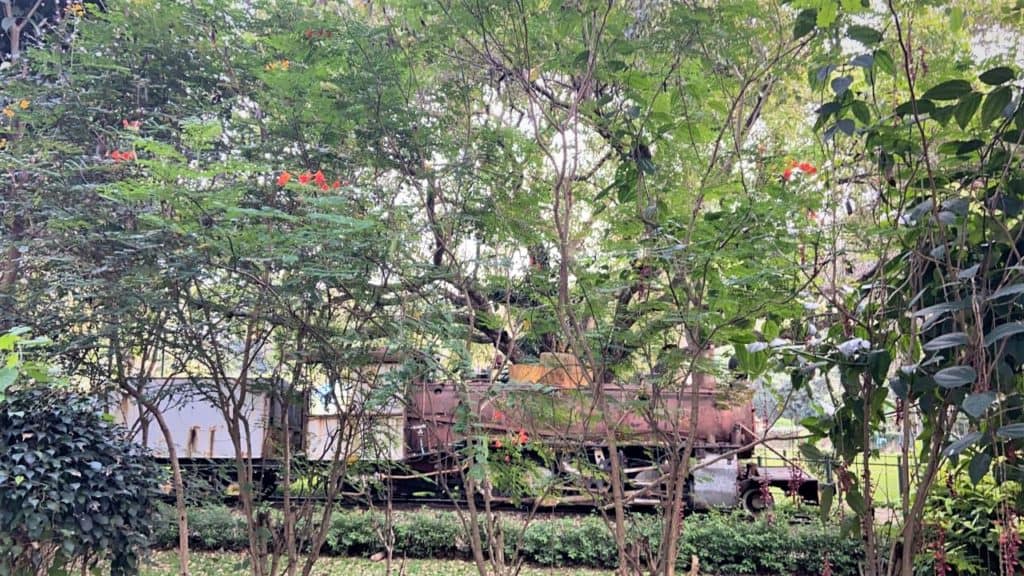

For long, I was intrigued by this derelict locomotive lying in the Indira Gandhi Musical Fountain Park opposite the Jawahar Lal Nehru Planetarium. I would have a fleeting glance of it while passing the gate. I had once seen it from up close and did not see any markings on it. Truly, it was a mystery locomotive.

A few years back I went to the park to do a detailed documentation of the locomotive. The more I looked at it, the prettier it seemed.

The first thing that one usually does when confronted with locomotives that don’t bear any markings, is to measure the gauge. My heart leapt when I discovered that the gauge of the tracks for this locomotive was 2 feet.

Gauging its past

India had two gauges for narrow gauge: 2 feet 6 inches and 2 feet. By a large measure, the 2 feet 6 inch gauge track mileage exceeded the 2 feet narrow gauge.

While there were several 2 feet narrow gauge lines in the pre-independence era, most were dismantled, excluding three, namely, the Darjeeling Himalayan Railway, the Matheran Light Railway and the Gwalior Light Railway.

I am familiar with the locomotives of the Matheran and Darjeeling Railways, both of which involve steep inclines and tight curves. Their locomotives are short and stubby; clearly, this locomotive did not belong to both those hill railways. I, therefore, narrowed down my search for the identity of this locomotive, to the Gwalior Light Railway.

The deductive method

The next step in identifying a locomotive is to look at the wheel arrangements. Steam Locomotives have a numbering style that lists out the numbers of the wheels in each section of the locomotive. Thus, for example, a 4-6-2 locomotive has four wheels in the pilot bogie, 6 driving wheels and 2 in the trailing bogie.

Read more: Why cities like Bengaluru fail to protect heritage

The locomotive in the park has the wheel arrangement 2-8-2. In other words, it has 8 driving wheels. That gives it a long, and in my view, pretty look. The more the driving wheels, the greater its tractive effort.

Besides, this locomotive also has a long tender, with 8 wheels. A tender is the carriage usually pulled just behind the engine, to carry coal and water for the engine. The large size of the tender is necessary because of the dry areas in which the locomotive used to run; it needs fewer stops to take in water and coal.

Luckily, the net has plenty of resources on Indian locomotives. Using pictures that were available, I further narrowed down my search to the 2-8-2 locomotives that ran in Gwalior. I zeroed in, tentatively, to this locomotive manufactured by the Baldwin Locomotive Works, Philadelphia, and delivered to India at around Independence.

However, could I be sure? I did not think so, because in the final analysis, the numbers on the locomotive must correspond with the numbers indicated by the manufacturer. Sadly, there were no numbers on the locomotive in the park.

The hidden number

Till, one day, I began to scrape away the dirt and the red oxide slapped on the locomotive, and discovered this. 812 was the number assigned to this locomotive by the Indian Railways.

I went scurrying back to the net to look at old pictures. Sadly, there were pictures of other locomotives, but none of 812.

So the mystery continued. I concluded that this locomotive could be from Baldwin; the engineering features and design style was very much like a miniature of the Baldwin meter gauge design, which I knew well, but one could never be sure.

Read more: How Bengaluru became the first Asian city to get electric street lamps 115 years ago

Around Christmas time, I chanced upon a bargain. A rare set of books, penned by one of the foremost archivists of Indian Steam Locomotives, was available on the net for an astoundingly low price. I ordered that set pronto. I had been eyeing them for 20 years, but could not get my hands on them as they were rare and super expensive.

A reference gem

Hugh Hughes’ four-volume labour of love, ‘Indian Locomotives’, is an invaluable guide for the dyed-in-the-wool Indian railway historian. The first three volumes deal with broad, meter and narrow gauge locomotives from 1851 to 1940. The latter volume is about locomotives from 1940 to 1990.

These volumes comprise very little prose; they mostly contain rare pictures and pages and pages of tables. Hughes says that the main object of these books is to list and describe all the locomotives that ran in India in that period.

As the early Indian railway companies all ran on the basis of government guarantees on assured rates of return, the Government directed these companies to give six-monthly returns, from the very inception of the railways.

Hughes delved through enough documents in the India Office archive in London, to compile his priceless tables. Given that locomotives underwent numerous changes in the numbering system as they transited from various private companies to the monolith of the Indian Railways and thence, to the various zones, this was a painstaking task.

Hughes is from New Zealand. Imagine. A New Zealander goes to the India Office in London, travels the length and breadth of India on rails, pores through mountains of post-independence Indian locomotive lists, and compiles the definitive list of Indian Locomotives.

Surprising find

I waited with bated breath for Hughes’ volumes; they arrived by post. And the mystery of our Park locomotive is solved. Locomotive no 812 is not from Baldwin Locomotive Works, Philadelphia. It is not the same loco as the one in the picture, as I had earlier, tentatively, suspected.

Locomotive no 812, is an NH/5 class locomotive. It is one of four manufactured and supplied in 1959 by Nippon Sharyo Limited, Japan.

This is a rare locomotive. A special one. I do not know how many Japanese-built locomotives survive. And it is the last of a special breed.

We must restore this locomotive to its former glory. I am already daydreaming about it. One has the choice of recreating the livery of the Central Railway, which took over the Scindia State Railway. But I would much rather restore it in the livery of the Scindia State Railway.

We must not only write to the Horticulture Department, but we must also write to His Excellency, the Ambassador of Japan in India. I have no doubt that they will be thrilled with this discovery and that they will put us in touch with Nippon Sharyo Limited. They could contribute to its restoration. This would be similar to how the Russian Government collaborated with the Government of India and the Government of Karnataka, for protection and restoration of the legacy of the Roerichs.

Want to know more about the mystery of the park engine?

Heritage Beku, a group of citizens working towards protecting the history that makes Bengaluru unique, along with Horticulture Department and South Western Railway, is organising a free, open-to-all event on February 20 at 4 pm at the Indira Gandhi Musical Fountain Park. For more details, click here.

Fascinating story. I wish more power to your pen. Look forward to more such pieces. Many thanks.

That is indeed a rare locomotive! The book set really served it purpose it seems. 🙂

Hats off for your keen observation skills, and your diligence in unravelling the mystery of this rare locomotive.

I sincerely hope that the concerned governments/agencies pitch in their resources for restoring this locomotive to its former glory. It would be the best reward for this effort of yours.

Wishing you the very best.

any photo Bardhhaman stem loco photo ?

please up load.

Great effort, Sir…how can we help even if it means writing to the concerned department to restore the loco? Pls let me know