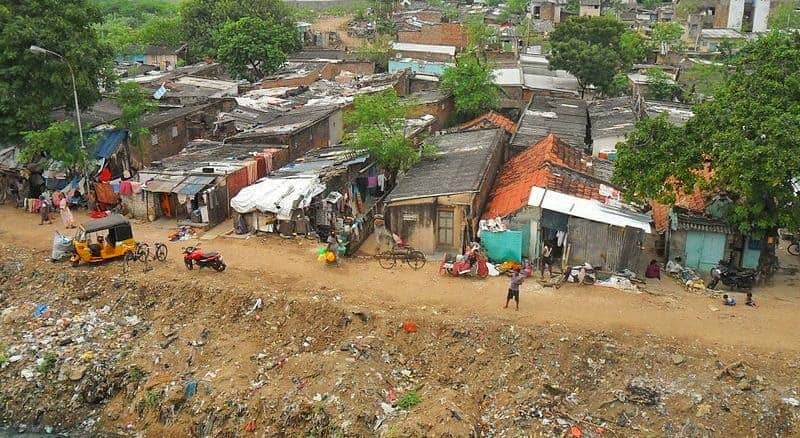

As one passes the bridge in Kotturpuram, the huge mound of construction debris that lies on the left, close to the banks of the Adyar River, cannot escape the eye. Amidst this debris lie the dreams of Kumari and hundreds of other families, whose story we narrated in an earlier report on Citizen Matters Chennai.

Kumari had bought with her hard-earned savings a 280-sq ft room in the Tamil Nadu Urban Habitat Development Board (TNUHDB) tenements that stood on this site. But that dream lasted for barely a year and a half. Then the Board decided to demolish these buildings and build new ones in their place. Kumari and other owners could only watch helplessly as their homes were reduced to the rubble that lies strewn around now.

In our earlier story, we also saw how this move pushed many families into a debt trap. High deposit amounts and rents, in addition to daily expenses and loss of livelihood, have made their financial position precarious. Many families have only just come to know of the beneficiary contribution (at least Rs 1.5 lakh) that they will have to pay to get allotments in the reconstructed tenements. But in the midst of all the hardship and uncertainties, what has kept them going is the promise of new homes within a period of two years.

But will that really happen? Can the TNUHDB really ensure that these tenements are completed and allotted within the promised time frame?

Status of reconstruction of the TNUHDB tenements in Chennai

According to highly placed official sources from the TNUHDB, as many as 25 sites of TNUHDB tenements in Chennai are selected for reconstruction under the Affordable Housing Scheme of the Central government. A technical committee consisting of engineers from TNUHDB and experts from Anna University inspected and evaluated the buildings. Considering the dilapidated condition of the buildings, they were recommended for demolition and reconstruction.

Of the 25 sites of TNUHDB tenements in Chennai, tenders have been awarded and a foundation stone has been laid for reconstruction in five places. Tenders are to be finalised for the other 20 sites in a month’s time. Families from almost all 25 sites have been evacuated and given financial assistance of Rs 24,000. In a few places, demolition works have also been completed.

The official assures that the reconstruction works will be completed in a period of two years or even before that as promised to the people.

Contrary to this promise made by the officials, the residents of the tenements find that even after more than five months of demolishing the houses in Kotturpuram, the officials are yet to remove the construction debris.

“If it takes five months even to remove the construction debris, how long is it going to take to reconstruct those buildings?” asks Kumari.

The status of the TNUHDB tenements demolished in Meenabal Sivaraj Nagar in March this year is also the same.

Reconstruction of many TNUHDB tenements took longer than promised

Sebastian, Coordinator of Nagarpura Kudiyiruppu Nila Urimai Kootamaipu, says, “From the track record, we have seen that the government has not completed the reconstruction in 18 months or two years as they promise. It takes a minimum of four to five years. Even after reconstruction is completed, the government takes years to hand over the houses to these families. Tenements in KP Park and Santhosh Nagar stand testimony to this.”

Explaining further, he says that the tenements constructed for the poor in KP Park were not allocated to the people even after two years after the construction was over. Eventually, when they were given the houses, the families found that the houses were of substandard quality.

Leaky ceilings, broken water pipes, damaged staircases, cracks in the walls and doors and faulty lifts were among the major issues pointed out by the residents.

Citing an example from the TNUHDB tenements in Chennai’s Santhosh Nagar, Vasudevan S of Meenabal Sivaraj Nagar TNUHDB Residents Welfare Association, says the residents of Santhosh Nagar vacated their houses in 2019.

“It took more than three years to complete the reconstruction. Then, there was a delay in getting the electricity, water and sewage connections for the dwelling units. The lack of coordination between the officials from various departments contributes to the delay in allocating the houses,” he adds.

Sebastian also points out that sometimes the delay is caused merely by the officials having to wait for the local politician’s/minister’s date for inaugurating the reconstructed building.

However, the officials defend saying that the TNUHDB officials monitor the construction progress through site inspections and reports at regular intervals. Interdepartmental meetings also happen almost every week. Hence, there is no lag in the interdepartmental communication.

Read more: Kannappar Thidal: Where residents continue their 20-year wait for a proper home

When asked about the delay in reconstruction in areas like Santhosh Nagar, the official from the TNUHDB elaborated on the challenges faced by them and the contractors involved in reconstruction.

“Mobilising the material for construction is a major challenge in a city like Chennai. We do not permit heavy vehicles during the daytime due to traffic congestion. Hence we have to transport the materials during the night. The second major challenge is finding a proper labour force for the construction works. Since the buildings are high-rise in nature, not all construction workers will be qualified for the job. Only a selected few can get the job done. Hence, that is a challenge,” says the officials.

Further, the contractors also face challenges as the fund flow is usually delayed in government projects. This burdens them adding to the escalating cost of construction materials.

“Only when we build high-rise buildings, we will be able to meet the increasing housing needs of the growing population. When we move out the people from these tenements, we find new settlements formed around the tenements. These are occupied by the extended families of those living in the tenements. In places where there were 100 dwelling units, we now have to build at least 150 dwelling units to ensure the extended families are also given proper shelter. The existing 100 dwelling units would have been in a measurement of 230 sq feet. But the ones we are building now will measure 400 sq feet (approximately 410 sq ft). Depending on the limitations of FSI, we will be able to accommodate all the people and their extended families in the same place. However, it is not possible in all cases. Hence, we are forced to provide them with houses elsewhere which the residents do not agree to. This also leads to delays in the project implementation and allotments,” the officials explain.

Read more: What Chennai must consider before an increase in Floor Space Index

How can the government help the people from falling into debt traps during the reconstruction of TNUHDB tenements in Chennai?

Vanessa Peter, Founder of the Information and Resource Centre for the Deprived Urban Communities (IRCDUC), suggests that the government must create a stock of houses that can be rented out to these families as alternative accommodation until the reconstruction is over.

“This is not a new scheme. The government used to provide transit shelters to the families when reconstruction is done. Since the quality of those shelters was poor, the families started moving out of the shelters. This is when the decision to provide financial assistance came in. However, insufficient financial assistance (Rs 24,000 for two years) still does not address the issue,” she says, adding that the alternative accommodation should be of good quality.

Land rights – a one-stop solution to Chennai’s housing issues

The argument put forth by the officials when asked about giving land rights to the people in the tenements is the lack of vacant lands in the city. When asked why they cannot give an undivided land share (ULS) to the families living in the TNUHDB tenements in Chennai as given to those in the private apartments, the officials say that the government is not claiming the land cost from any residents and so they are not giving ULS.

“This is the reason we are able to give the houses with a beneficiary contribution as low as Rs 1.5 lakhs per dwelling unit,” says the official.

Sudhir Kumar, an architect from Chennai points out that mapping of vacant lands in the city was one of the main components of the Rajiv Awas Yojana scheme (slum-free cities) that was brought in 2013 (which also had an implementation period from 2013 to 2022).

“Consultants were hired for doing satellite mapping of vacant lands in Chennai. However, to this day the report has not been made public yet. Besides, as much as 11 sq km of land were confiscated while implementing the Fixation of Ceiling on Land Act, 1961. Though the law is not in place now, it still had records of 11 sq km of excess urban land in Chennai. This is almost 1% of the Chennai Metropolitan Area. Why cannot the government give these lands to those poor people?” he asks, adding that without having rights over the land, the people are prone to evictions at any point in time.

On the other hand, Vanessa suggests the government opt for in-situ slum upgradation than building multi-storey buildings. She says, “The government was earlier giving pattas for the in-situ slum families by regularising the lands and giving the families provision to build concrete houses in the same land. The advantage is that the families can expand the houses vertically based on their needs. This will help to meet the space for the expanding families. However, the government opted for the multi-storey model, an economically costly tenement scheme that gives no space for expansion as the families grow.”

Stressing why it is important to give land rights to the people, she says slum development does not only mean that thatched houses are converted to concrete houses. It also means that the social mobility of the slum dwellers is ensured.

“A lesson from the previous mistakes is that multistorey construction will not address urban deprivation by itself. Instead of relocating the socially and economically deprived families to multi-storey houses which are later being demolished in such cases, the in-situ upgradation can benefit them better as it ensures better social mobility,” she says.

While we look for alternative solutions to address urban deprivation, it is also pertinent to note that seeing housing as a standalone approach to addressing urban deprivation has failed long ago. Giving land rights to the people will not only give them a sense of ownership of their land and the building but also make them actively take part in looking after the land and the building.