The end of life of textiles is creating a huge cost that no one is bearing right now. Only forcing textile industries take back or pay for storage or own the end of life costs will this very problematic textile waste be treated in a more sustainable manner.

This is the first of a two part series on the mounting textile waste that Bangalore generates and the various issues in disposing-recycling-reusing them.

“There is something about online shopping from home, from the array of choices, not to mention the cheap prices,” says Sheeja, a senior HR Manager who recently relocated to Bangalore from Mumbai. “I don’t feel bad about the fact that I can discard clothes I purchased online in a shorter span, as they are cheap”.

“With online shopping, I find it easier to get garments cheap and my children also feel happy that they are getting something new,” says Shilpa, a domestic worker who works in three houses in Bengaluru. “And we feel less guilty when it is time to discard”.

That sentiment echoes across the country. According to a survey carried out by ProdegeMR, around 81% of respondents bought apparel online from Amazon in May 2019. About 76% preferred Flipkart for apparel purchases.

But the problem is, as easy it is to buy, it is equally easy to trash garments.

Some figures

According to the Statista Research Department, at the end of fiscal year 2019, India’s total textiles production was approximately 71 billion square metres with a market value of textile 106 billion dollars, which is estimated to reach 190 billion dollars by 2026. Karnataka accounts for about 20% of India’s garment production with this segment accounting for two thirds of the state’s industrial output, apart from being a major employer.

Read more: Brand Audit 2021: Here are Karnataka’s top producers of plastic waste

In India, cloth and other household linen were rarely thrown out as rubbish, as it was customary to pass it on to other family members or as gifts, or used for mopping, cleaning materials, or stitched to make quilts, or sometimes exchanged. Each piece of garment had a story around it, evoking a sentimental value and offering a window into the history of the household.

In the book Recycling Indian Clothing, author Lucy Norris notes: “Indian society is still partially a cloth economy, where cloth is both a currency and a means of incorporation, which has profound implications for disposal practices”. But all this has changed since the 1990s, when the Indian economy opened up. Rising urban middle class, with significant disposable income, saw the beginning of a consumption boom.

“One of the many changes I have seen in my 20 years of waste picking is around clothes and other textiles,” says Krishna, a waste entrepreneur and a Dry Waste Collection Centre Operator in Ward 112, Domlur, “When I was growing up, we were called rag pickers, as many of us would collect clothes in exchange for vessels. Nowadays, clothes, even brand new clothing with the packaging intact, are dumped as garbage”.

Disposal and reclamation

Bengaluru, like all Indian cities, is facing a massive influx of textile waste. According to the Indian Textile Journal, it is estimated that more than one million tons of textiles are thrown away every year, with households discarding the highest proportion. However, lack of reliable data makes the problem difficult to comprehend.

A Deccan Herald article in December 2021, stated that “textiles are the third largest source of municipal waste, with more than 70%-80% being sent to landfills or incinerated, instead of being recycled or reprocessed”. An important point for consideration is that the textile industry is the third biggest consumer of plastic.

A case in point is the Karnataka Textile Policy 2019-24 which aims to position Karnataka as a significant manufacturer and exporter of Technical Textiles, which are engineered products with a definite functionality. They are manufactured using natural as well as man-made fibres such as Nomex, Kevlar, Spandex, Twaron that exhibit enhanced functional properties such as higher tenacity, excellent insulation, improved thermal resistance etc. These products find end-use applications across multiple non-conventional textile industries such as healthcare, construction, automobile, aerospace, sports, defence, and agriculture.

Worried about the rising textile waste in the dry waste stream, in 2018 Hasiru Dala, in collaboration with the Resident Welfare Association (RWA) in ward no. 112, Domlur, experimented with a separate collection of good quality garments and other products like bed sheets, pillows etc.

The three week long initiative, titled ‘Hasiru Batte’, meaning Green Clothes, had twin goals of Identifying markets and techniques for textile waste, away from landfills and incinerators and helping waste pickers create new business models for traditionally unrecyclable textile waste.

Read more: How the 2Bin1Bag initiative helped Bengaluru score high in waste segregation

“We conducted door-to-door awareness for three weeks continuously, in the entire block of the ward and asked residents to give textile waste separately,” says Krishna. “We distributed pamphlets and announced the collection date and residents were very cooperative. Some of them packed the clothes really well, clean and neatly ironed. I could actually use many of them for myself. We categorised the clothes in three streams—good quality, repairable quality and poor quality. The biggest challenge was dirty clothes for which we don’t have any alternatives. I honestly believe we need a solution for that beyond burning and dumping”.

Hasiru Dala Cloth Audits

In 2019, a cloth audit was conducted by Hasiru Dala in four wards of the city on the request of Almitra Patel, an environment policy advocate. Her landmark 1996 Public Interest Litigation in the Supreme Court (Almitra Patel vs Union of India) against open dumping of municipal solid waste led to the drafting of the Municipal Solid Waste Management Rules, 2000.

The Hasiru Dala audit was conducted over three days on January 10th, 11th and 12th, 2019. Households in the wards varied from a little over 6000 to over 31,000.

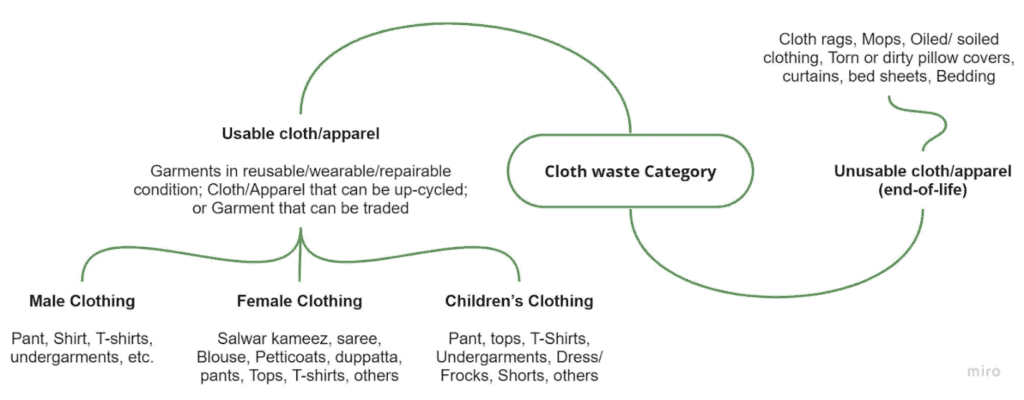

The incoming quantity of dry waste and total quantity of textile waste was weighed separately. Post that, the textile waste was separated into two categories and weighed again —post-consumer reusable (repairable or reuse-as-is) cloth waste and post-consumer non-reusable (end-of-life) cloth waste.

The survey showed that the wards received an average of 3.5% of cloth waste from the total dry waste collection. Ward 41 Peenya, being an industrial area, received an average of 9% of cloth waste with 19,919 households, which is 3.3 times higher as compared to ward 150 Bellandur, a residential area, which received an average of 2.7% of cloth waste with 31,183 households.

Mens wear clothing was predominant with 42.41%, followed by women’s wear with 35.02%, and lastly children’s wear with 22.57%. The difference between the three of them was minimal. The survey also revealed that from the total cloth waste generated, only 14.5% could not be recycled or were otherwise unusable; while the scope for reusable clothes was about 85.5%.

Similar data collection in 2021 from 15 DWCCs supported by Hasiru Dala from wards which had robust source segregation and a fully functional DWCC, showed cloth waste comprised 7-12% of the total dry waste collected. The variance in percentage of cloth waste is owing to better quality source segregation and better reporting of waste composition from the DWCCs.

With inputs from Shekar Prabhakar, Karthik Natarajan, Indha Mahoor, Vishwanath C, Akbar A and Aishwarya. Special thanks to Beula Anthony, for transcribing the interviews.