The pandemic wrecked the livelihoods of many people in Chennai. The state government set up the Dr C Rangarajan Committee to provide medium-term policy suggestions to mitigate the economic impact of COVID-19. One of the suggestions of the committee was the creation of a daily wage programme for the urban poor.

Taking this into consideration, the Tamil Nadu government rolled out an Urban Employment Scheme (TNUES) in Chennai and other municipal corporations. The scheme mirrors the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) and is designed to provide guaranteed employment for 100 days in a year.

“The scheme has been rolled out on a pilot basis in two zones in Chennai at present” said an Executive Engineer (EE) of the Works Department of Greater Chennai Corporation. Zones 4 and 6 have been chosen to test the scheme before its expansion to the rest of the city.

Aim of Tamil Nadu Urban Employment Scheme

The Urban Employment Guarantee scheme aims to provide employment opportunities to the economically disadvantaged among the local population, between the age group of 18 and 60. The state government has earmarked Rs. 85 crore for the scheme in Chennai and other corporations in Tamil Nadu. The state releases the funds based on the need and performance of the urban local body.

The scheme also promises gender equity, where women and men get equal wages, and the former will get at least half the total person-days of work.

“Mostly, women sign-up for the scheme to help with household expenses,” said B Vimala, Councillor of Ward 41 in Kodungaiyur.

“There would be some women who would have to go to work in faraway places. The Urban Employment Scheme at a local level would help women to work flexibly in their own wards and also support their households,” said Dr. Sowmya Dhanaraj, an Assistant Professor at the Madras School of Economics.

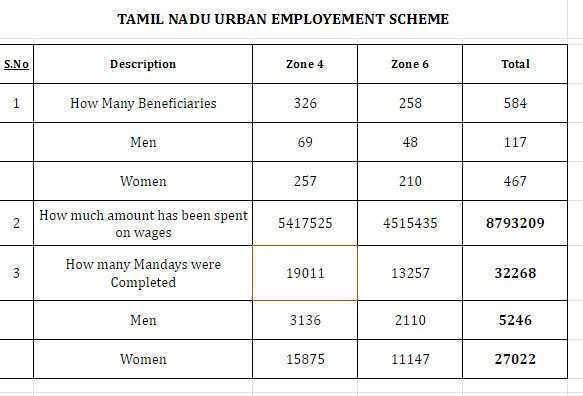

The data available bears this out as more women have signed up for the scheme compared to men. So far there have been 467 women beneficiaries against 117 men, since the scheme was first rolled out in March.

In Chennai, Tondiarpet (Zone 4) and Thiru. Vi. Ka. Nagar (Zone 6) are the zones where the scheme has been piloted. According to the Tamil Nadu Integrated Poverty Portal Services, those two zones have the most number of households below the poverty line, with 50,544 families and 44,169 families in Zones 4 and 6 respectively. Apart from that, 45% of families in these two zones live in poverty, points data.

Read more: Councillor talk: In ward 41, B Vimala wants to fix Kodungaiyur dumpyard

Eligibility, selection and training

People between the age of 18 – 60 can sign up for the Urban Employment Scheme by filling out an application form distributed by the civic body.

“Ideally, the workers must reside in the ward where the work is carried out. But they can also work in the neighbouring wards based on the availability of jobs,” said the EE.

For instance, a person who can give address proof that he or she is a resident of Ward 41 can seek local employment in Ward 40 or 42, if there is work in these neighbouring wards. They would have to work on all days of the week except Sundays.

“The selection process involves verifying address proof, willingness to work, and income certificates,” said the EE.

The selected applicants will be provided with a job card, which works like an ID card under TNUES.

The ULBs electronically pay the workers every 15 days based on a specified quantum of work. Therefore, people applying for work under the scheme share their bank account details.

The works recommended under TNUES include flood mitigation procedures like desilting stormwater drains, maintaining parks and plantations, operating micro composting and resource recovery facilities, and building footpaths and traffic islands. .

According to the G.O., the local bodies will select a worker and train them to oversee the work and maintain the attendance of other workers. There should be one work monitor for every 50 workers.

Current status of Tamil Nadu Urban Employment Scheme in Chennai

We visited Kodungaiyur (Ward 41; Zone 4) in Tondiarpet and Perambur (Ward 71; Zone 6) in Thiru. Vi. Ka. Nagar to take stock of the ground reality of the scheme.

The number of beneficiaries is not constant, say the officials from GCC and the respective zonal offices.

“Some days, 210 people come for work, while on other days, only 140 people work in the area,” said the Zonal officer of Zone 4.

Zone 4 saw a total of 326 beneficiaries who were engaged for 19011 person-days of desilting the stormwater drains from the end of March, when the scheme was rolled out, till the second week of August. The workers in the wards of Zone 4 received a total of Rs. 54.17 lakhs as wages.

In Zone 6, there have been a total of 258 beneficiaries engaged for 13257 person-days of desilting. The workers received Rs 45.15 lakhs as wages.

Desilting of stormwater drains is the only work that is being carried out in the two zones under the scheme in the run-up to the monsoon season in Chennai, confirmed the EE. The area engineers or other personnel of the wards take the attendance in the morning and after lunch, said the officer from the Tondiarpet zone.

“Usually on the first day of work, we demonstrate the work for the benefit of the new workers,” said an official from Perambur.

“We used to come in the morning around 9 am and leave by 4.30 pm,” said Rani* a worker from Zone 6, whose tenure under the Urban Employment Scheme has since ended. “They gave us a coat, gloves, spade and a big bag to pick up the silt.”

“The gig can exceed 100 days. They can approach the area engineer of the ward and request an extension,” said the Zonal Officer of Zone 4.

“People from Thiru. vi. ka. Nagar zone can apply for the Urban Employment Scheme in Chennai even now, until they complete desilting all the 393 drains in the zone,” said the EE.

Workers near Perambur in Zone 6 said that their 100-day tenure was over last month and have approached the authorities to extend their tenure.

Working conditions under urban employment scheme in Chennai

“Around 2000 people in my ward received the forms for a 100-day job under the TNUES during the beginning of 2022. But now, we have only three women beneficiaries of the scheme in our ward. We started out with 12 beneficiaries under the Urban Employment Scheme,” said Vimala. “Not everyone could regularly work due to many reasons like poor health and being unable to do back-breaking work in the hot sun.”

The G.O.regarding the scheme stated that the scheme would include unskilled, semi-skilled and skilled people. Vimala said that even degree-holders applied for the 100-day employment scheme without knowing the nature of the work. However, only unskilled labour was necessary for desilting drains.

The officials said that not everyone who gets the job card turns up for work.

“Even if one of us is absent for a day, nobody would question us. We will not get payment on the days we don’t go,” said Rani. “They initially informed us that our job would be to sweep parks and gardens when we signed up for the scheme. Later, they said that we have to do desilting. It was very hard to meet the target. We are still waiting for when they will call us for sweeping parks,” said Rani.

Due to sewage mixing in the stormwater drains, the workers found it very hard to desilt the drains. “The smell was very bad,” remarked Rani.

Workers from Zone 6 said that they received a coat and gloves. But according to Vimala, the workers from Zone 4 only received bags and a spade, and no protective gear.

Issues in payment of wages

“We pay a daily wage of Rs 382 for one cubic metre or 16 bags of silt removed from the drain in a day. Every 15 days, the worker must get the wages,” said the Zonal Officer from Zone 4. “If a worker removes lesser silt, then the pay will be proportional to that. If a couple of bags is less, we pay around Rs. 342.”

At the beginning of August, Goverdhan, a resident from Perambur noticed a group of workers standing outside the office of the ward councillor, requesting their wages. Goverdhan had enquired with workers in his ward about their wages. “Even though their daily wage is Rs. 382, they are getting only in the range of Rs. 350-360.”

“Many people got around Rs. 150-Rs. 200 in other wards of the zone. In Kodungaiyur, the workers got Rs. 300 or so,” added Vimala.

Rani also raised the issue of delay in payment of wages for two months. “The daily wage simply supplements the earnings of the other members of the household. This amount is not enough for all the expenditure,” said Rani.

Furthermore, the daily minimum wage for manual workers in Tamil Nadu is Rs. 381.38, as of April 2022.

“Minimum wages are prescribed for the type of work, not nature or tenure of the contract. They can seek legal aid in labour courts if the stipulated minimum wage is not met,” said Anjor Bhaskar, a teaching faculty at Azim Premji University, specialising in sustainable livelihoods.

Read more: Explainer: How to access free legal aid in Chennai

Expanding the scope of urban employment in Chennai

“We cannot simply look at this as a scheme to help the urban poor. We should also look to make the cities better using the workers for the scheme to realise its maximum potential,” noted Anjor. He suggested that the local workers could be roped in for greening jobs like planting trees, maintaining composting sites, and building rainwater harvesting structures in public institutions. “The city can also establish training centres to help people skill up on greening jobs.”

To understand the capacity of an average worker, Anjor recommends a time-motion study to be conducted on the existing urban employment scheme in Chennai. “Workers of different genders and age groups can be asked to carry out the task in eight hours. Then we can take the mean of their productivities and then set their daily targets.”

Vimala was of the view that there is a huge scope for expanding the scheme. “The workers can be used to clean and maintain public places like schools and plant trees on the roads. If I have 400 workers in my ward, I can really change how it looks.”

While the scheme has help workers get guaranteed wages during a time of economic hardship, the scope is ripe for expansion. Even as the Dr C Rangarajan Committee outlined a range of tasks that the workers can be engaged in, only desilting works have been carried out in the six months since its launch.

A large number of the beneficiaries were middle-aged. There has been little to no interest from youngsters seeking employment under this scheme. The arduous nature of work and the issues with payments are also a deterrent for many to take up work under the scheme, thereby defeating its larger purpose.

An urgent reimagination of what short and medium-term employment could mean in an urban context is necessary before the scheme is rolled out to the larger city, along with the incorporation of key learnings from the two zones where it is being piloted.

*name changed on request

Informative article on Urban Employment scheme in Chennai.

Will the Urban Employment Scheme in Chennai end the woes of urban poor? That’s the heading. The article provides a status report. It leaves the readers with a question mark.

1. Who is the target customer of this

script?

2. What is the value proposition to that

customer?

3. What are the essential capabilities

needed to deliver that value

proposition?

Without clear and coherent answers to these three questions, one may have an exciting vision, a compelling mission, clear goals, but when one doesn’t have an ambitious strategic plan any actions under way…is but, watering sea sand.