Hadu Bahera owns a ‘home’ for 12-hours every day. During this time, the 51-year-old loom worker inhabits a six-by-three-feet space in a dingy room on Ved Road in north Surat.

His co-worker uses the same space for the other 12 hours – depending on their shifts, from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. or the reverse. The occasional ‘holidays’ – when there is a power cut – are days to be dreaded. Nearly 60 workers must then fit into a 500-square feet room at Mahavir Mess, where Bahera is presently space-sharing.

The summer months – when temperatures reach 40 degrees Celcius – are miserable. “Some of the halls [large rooms where the workers stay] are dark, there is no ventilation,” says Behera, who came to Surat from Kusalapalli village in Purusottampur block of Odisha’s Ganjam district in 1983. “Even after a long, difficult day at the loom, it is not possible for us to rest comfortably.”

Like Behera, a large number of powerloom workers in Surat, most of them migrants from Ganjam district in Odisha, reside in dormitories or ‘mess rooms’, where they get spaces on a first-come basis after returning from their annual visit to Ganjam. The rooms, all in industrial neighbourhoods, are sometimes just metres away from the loom units. The high-decibel khat-khat sound of the machines is audible even as they lie on their makeshift beds after a gruelling 12-hour shift.

Around 8 lakh workers from Odisha, after strenuous shifts in Surat’s power looms, stay in rotation in crowded rooms, amid power cuts, scarce water, filth and noise. Pic: Reetika Revathy Subramanian/PARI

Surat is home to at least 800,000 workers from Ganjam, estimates the Surat Odia Welfare Association. Aajeevika Bureau, an organisation working with migrants in Gujarat, Rajasthan and Maharashtra, puts the number at over 600,000 migrants at the city’s 1.5 million loom machines.

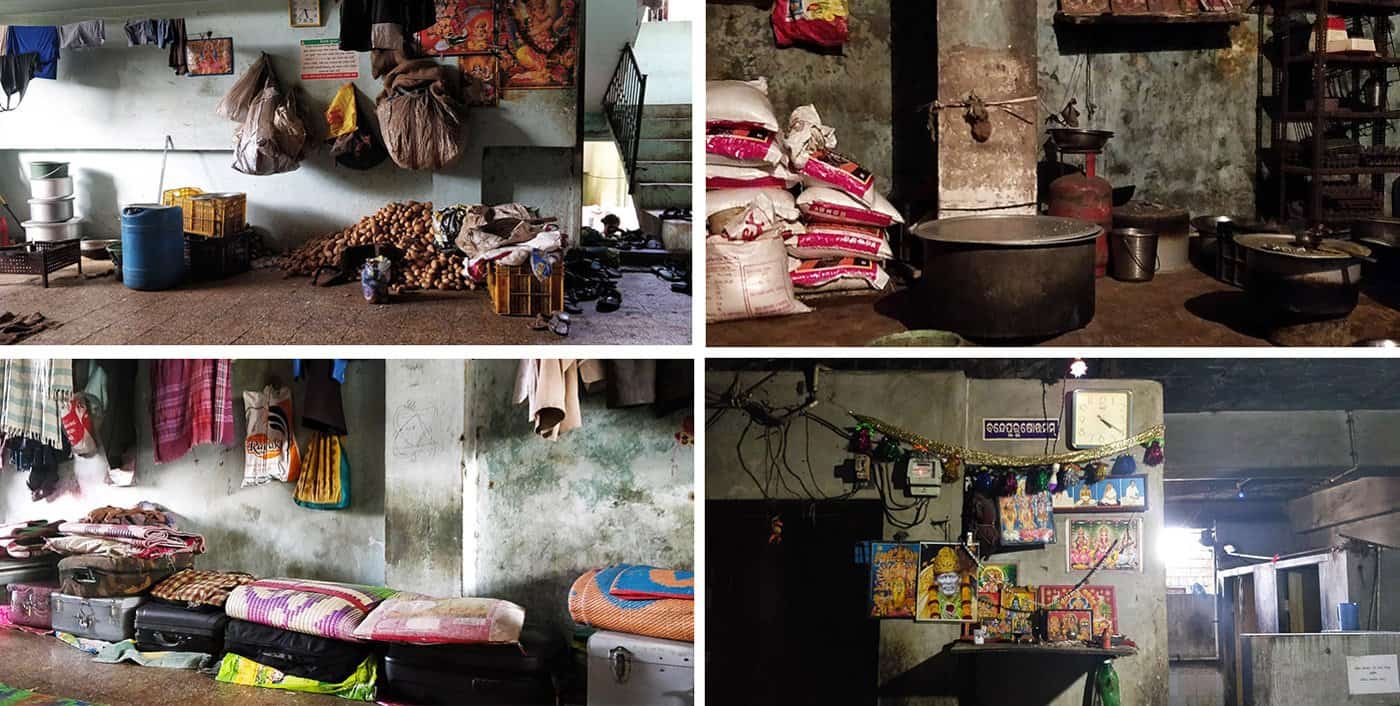

They live in 500 to 800-square feet rooms, each densely packed with 60 to 100 workers across two shifts. They sleep on worn mattresses sometimes infested with bed bugs. The blood of crushed bugs is visible on the grimy walls. On some walls, the workers have scribbled their names in Odia. There are termites here and occasionally rats scurrying about too. During the summer, the workers prefer to sleep on the bare floor or a plastic sheet because the mattresses are shared and get damp with sweat, leaving behind a stench.

Storage boxes and bags are placed one above the other at the head of each shared space. In addition to three sets of clothes on average and a few personal items, these contain a thin blanket for cooler nights, some cash, and pictures of gods.

Each room has two toilets at one end that all the occupants use. The kitchen is usually right next to the toilets. The water for bathing, drinking and cooking comes from a common source. Supply is intermittent, and water is stored in a tank or plastic drum in most mess rooms, so the workers are unable to bathe every day.

The few fans in each room barely beat the heat. In the main city, where Mahavir Mess is located, the power cuts are rare, but on the outskirts, in areas such as Anjani and Sayan, once every week, the Dakshin Gujarat Vidyut Company Limited switches off electricity for 4 to 6 hours. Mahavir Mess also has three windows, which makes it a sought-after option. Some rooms – in Kashinath Bhai Mess in Fulwadi in north Surat, for instance – are windowless, with only a tiny door at one end of the rectangular halls, which allows in a bit of air and light.

The poor ventilation, dense occupancy and inadequate water all cause frequent illnesses. In February 2018, Krishna Subhas Goud, a 28-year-old loom worker, died after contracting tuberculosis 18 months earlier. Goud stayed in Shambunath Sahu’s mess room in Fulwadi, which he shared with around 35 other workers. He went back to Ganjam and started the standard TB treatment. But with money running out, he returned to Surat, where it became difficult for him to continue the medicines. And it was difficult to even get restful sleep in the packed room.

Top row: In most mess rooms, the cooking area and supplies are close to the toilets. Bottom row: Workers keep their bags and belongings piled up at their spot; their bags include photos of gods, and many rooms also have a small prayer area. Pics: Reetika Revathy Subramanian/PARI

“Diseases such as tuberculosis are extremely contagious. And there is no escaping the crowd and dirt in the mess rooms,” says Sanjay Patel, centre coordinator, Aajeevika Bureau, Surat, who has been trying to obtain compensation for Goud’s family. “Since Goud died in the room and not in the loom unit, his employer is refusing to pay compensation…but with the workspace and the living rooms so closely interlinked, it is difficult to tell the exploitation apart.”

Barely four months later, in June 2018, 18-year-old Santosh Gouda, a loom worker from Biranchipur village in Ganjam’s Buguda tehsil, succumbed to a sudden illness. Two nights after he became sick with fever, cold and dysentery, Gouda died inside the toilet at Bhagwan Bhai Mess in Mina Nagar. “He didn’t even go to the doctor,” said a co-worker staying in the same rooms. “He was in Surat for nearly three years, but did not have any relatives or close friends here. We didn’t send his body back to his family, and performed his last rites here in Surat.”

Some rooms located on the top floors of buildings are said to be open at one end. “There have been cases of workers who have fallen off and died,” says Dr. Ramani Atkuri, a public health physician and consultant with Aajeevika Bureau. “The mess rooms are overcrowded, ill-lit and ill-ventilated,” she adds. “Such conditions are conducive to the spread of infectious diseases, from scabies and fungal infections of the skin, to malaria and tuberculosis.”

The state, however, has clearly marked the borders between ‘work’ and ‘home’. According to Nilay H. Pandya, former assistant director, Powerloom Service Centre ( set up by the Union Ministry of Textiles), Surat, compensation and insurance benefits only apply to injuries or deaths reported inside the factory. “The powerloom sector is extremely decentralised,” says Pandya, who was overseeing the ministry’s Group Insurance Scheme for Powerloom Weavers in Surat. “Not even 10 per cent of the workers have been registered under the insurance scheme as of now.”

The scheme was launched in July 2003. The worker pays an annual premium of Rs. 80 (with Rs. 290 added by the government and Rs. 100 from the Social Security Fund). He or his family can claim Rs. 60,000 in the case of a natural death, Rs. 1,50,000 in the case of an accidental death, Rs. 1,50,000 for total permanent disability, and Rs. 75,000 for partial permanent disability. “However, the rooms they live in do not fall within the ambit of our work,” Pandya says.

Among these rooms is Shambunath Sahu’s mess, home to around 70 workers (in two batches). It is located in a building that houses eight mess rooms on five floors, at the centre of the Fulwadi industrial area. The loud noise of the looms reverberates through the rooms. The rickety stairway is packed with filth, sludge and stoves with rice and dal kept to boil. The mess managers only clean the rooms, the corridors and stairs remain strewn with dirt. Garbage vans of the Surat Municipal Corporation don’t come to the area regularly, so heaps of garbage pile up for weeks.

The mess managers only clean the rooms, the streets and corridors remains strewn with garbage, dirt and sludge. Pic: Reetika Revathy Subramanian/PARI

During the monsoon months, rain water sometimes enters the rooms and corridors of buildings below street level, making them slippery and damp. It’s then difficult for the workers to dry their clothes. “We end up wearing damp clothes to work, we don’t have a choice,” said Ramchandra Pradhan, 52, a loom worker from Balichai village in Polasara block, who has lived in the mess rooms of Surat for three decades. ”

Sahu’s 500-square feet mess, like other such rooms, houses a kitchen with huge utensils, a prayer space, two toilets, a stock of vegetables, stacks of rice sacks – and 35 workers and their baggage. Sahu, a migrant from Sanabaragam village in Ganjam’s Polasara block, says the workers are fed “nutritious food” and the mess is “kept clean.”

Another mess manager in Sahyog Industrial Area in Fulwadi, 48-year-old Shankar Sahu, from Nimina village in Polasara block, says, “Every week, I have to purchase 200 kilos of potatoes. I prepare two full meals every day and feed around 70. The workers get angry if we don’t feed them well.” With the help of a cook, Sahu prepares rice, dal, vegetables and gravy. “I also include fish, eggs and chicken [twice a week].” Red meat is served once a month.

The cooking oil reused to prepare multiple meals is also affecting the workers’ health. In March 2018, Aajeevika Bureau surveyed the eating patterns of people in 32 mess rooms in Mina Nagar and Fulwadi, and found that the daily consumption of fat was 294 per cent of the ‘recommended dietary allowance’ (RDA, devised by the American Food and Nutrition Board), and the salt consumption was a huge 376 per cent. ““Hypertension is found more among workers in the older age groups, but a poor lipid profile was present across the ages,” says Dr. Atkuri.

The mess rooms are usually owned by local businessmen, who rent them out to the managers – most of them from Ganjam district. The managers pay a monthly rent of Rs 15,000-Rs 20,000 to the owners, and in turn collect Rs. 2,500 every month from each worker as rent and meal payment.

“There is no cap on the number of workers we can take into the rooms. The more workers we accommodate, the more money we can earn,” says Kashinath Gouda, 52, the owner-manager of Kashinath Bhai Mess in Fulwadi. “The workers come in two shifts….yet the profit margin is not very high for the managers. But without doubt, it is much better than working in the loom.”Gouda came to Surat from Tentulia village in Polasara block in the mid-1980s. “I worked on the khat-khat machine for nearly 20 years. It was a difficult life, I could barely save any money,” he says. “Around 10 years ago, I started managing this mess room. It’s a 24-hour job because the workers stay in two shifts. It is challenging to run the mess because some workers get aggressive and violent. But it’s definitely a better life than in the looms. I go back home to my wife and two children every year. Once my children find jobs, I plan to return to my village in a few years.”

With the strenuous work hours and the excruciating living conditions, many workers turn to alcohol. Since alcohol is banned in Gujarat, they purchase country liquor sold clandestinely in polythene bags for Rs. 20 for 250 ml by hole-in-the-wall shops across the industrial neighbourhoods.

“So many young workers are driven to alcohol,” says Subrat Gouda, who manages Bhagwan Mess in the Anjani industrial area in north Surat. “After their shifts, they head straight to the [liquor] stalls. It becomes very difficult to handle them once they return to the rooms. They get very violent and abusive.” Pramod Bisoyi, who manages a mess nearby, adds, “The workers lead difficult and lonely lives away from their family members. There is no entertainment or relaxation in this industry. Alcohol often becomes their only option to temporarily escape this world.”

Kanhu Pradhan, from Sanabaragam village in Polasara block, is struggling to quit his addiction. “I drink around three days every week. How else can I relax after working for so long?” asks the 28-year-old, on his way back from the loom unit at Sahyog Industrial Unit in Fulwadi. “I am also constantly stressed about saving money to send back home. I know it is harmful to drink so much, but it is really difficult to stop.”

It is 6 pm and 38-year-old Shyamsundar Sahu is getting ready for his night shift in the loom on Ved Road – his routine for 22 years. “I moved here at the age of 16. Ever since, apart from my annual visit home to Balichai village, I have worked and lived in this same manner,” says the father of three. “My family doesn’t know that I live in such a room with so many people. I don’t have a choice. Sometimes, it is more comfortable to clock-in longer shifts in the unit.” Then he crosses the 10-feet wide road from his ‘home’ to enter the factory

This article was originally published in the People’s Archive of Rural India on October 22, 2018.