If last year’s BBMP budget is any indicator, health and education are likely to once again be at the lower end of the allocation scale this year too. With no elected Council, BBMP had sought suggestions directly from citizens on what the 2022-2023 city budget should focus on.

It is probably safe to assume that health and education were high on people’s priorities, especially with the impacts of COVID. Yet, infrastructure seems to be the BBMP’s favourite, despite the myriad problems citizens are facing with ongoing delayed and incomplete projects.

In the 2021-2022 budget, BBMP’s total outlay was Rs 9,286 crore. Of this, the highest allocation – Rs 5417 cr (58%) – was for the Public Works Department, primarily for building and maintaining roads, stormwater drains, parks, etc. Of this amount, small proportions were for building and maintaining school and hospital buildings.

The second highest allocation was for solid waste management at Rs 1622 crore.

As usual, allocation for public health was much lower (Rs 336 cr) despite COVID. As also for public education (Rs 83.9 cr) and social welfare (Rs 319 cr).

Citizen Matters spoke to some Bengalureans for their take on how the 2022-2023 budget allocations should be made for the city—which projects should be prioritised, should BBMP be doing things differently, is a rethink needed in the context of COVID?

This is what they said.

Costly infra projects are not improving life in the city

Despite the allocation of around Rs 5,000 cr annually, poor quality continues to dog Bengaluru’s infrastructure projects. Urbanist Ashwin Mahesh says this will change only if BBMP first fixes design instead of spending repeatedly on flawed projects.

“Globally, cities have a street design manual which specifies how each road should be built,” says Ashwin. “For example, for a 30-ft road, the manual would mention the space needed for footpath, whether the road should be a one-way, specifications for the footpath, etc. And the contractor should be obliged to follow these standards. But currently no standards are followed in BBMP”.

As an example, Ashwin compared expenditure and conditions of Raja Ram Mohan Roy Road and Vittal Mallya Road. The comparision showed more money had been spent on the former over the past 5-7 years for repeated works, yet it remains less walkable. In contrast, less was spent in the same period on Vittal Mallya Road, which had been built as per TenderSURE norms, and is far more walkable.

“Similarly, BBMP gives contracts for cheaper rectangular-shaped stormwater drains rather than for cylindrical drains that cost more but allows better water flow,” points out Ashwin.

“When building a clinic or school too, BBMP should construct one as a standard, and then replicate it,” says Ashwin. He advocates standardised manuals, which are mandatorily included in the construction contract, for the design and use of all infrastructure in Bengaluru, .

High allocations for waste management isn’t solving the problem

High allocations for SWM have not solved Bengaluru’s garbage problem either. A large proportion of the SWM budget is usually for paying contractors for door-to-door collection and transportation of waste. SWM experts say that the city should invest in decentralised waste management facilities, which will reduce payments to contractors in the long term and also help solve the garbage issue.

Sandya Narayanan of Solid Waste Management Round Table (SWMRT) says that Bengaluru currently has the capacity to process only 1,200 tonnes of waste out of the 5,500 tonnes it generates daily. Considering the dry waste component alone, the processing capacity is only 200-300 tonnes whereas daily generation is 900-1000 tonnes.

“Bengaluru should have ward-level processing centres for different streams of waste (dry waste, leaf waste, animal waste, construction debris, etc) so that mixed waste is not dumped in the city or transported by contractors for long distances,” says Sandya. “For this, Bengaluru would have to spend around Rs 1,000 cr over the next 5-6 years, but this investment can be recovered in the long term”.

For instance, SWMRT had earlier proposed to the BBMP to upgrade DWCCs (Dry Waste Collection Centres) at the cost of Rs 12 lakh each, which could then be recovered in the next five years.

However, despite SWMRT’s repeated demands, BBMP has been allocating little for decentralised waste management. Sandya says that even these amounts remain unspent or get spent under other heads. She gives the example of Rs 15 lakh allocation per ward for leaf shredder-cutters, made two years ago, which has remained on paper.

Kathyayini Chamaraj of the NGO CIVIC echoes the demand for decentralised waste management facilities. She also suggests that BBMP can provide subsidised equipment for composting or biomethanation to households directly (as has been done in Alappuzha in Kerala), and set up streetside composting bins managed by pourakarmikas (like in HSR Layout) for households unable to do it themselves.

Green budget

Ulka Kelkar, Director, Climate, at WRI India says that BBMP could adopt climate budget tagging, as states like Orissa and Bihar are doing: “That is, when they make their budget for any scheme, they identify the component towards green measures and climate action,” says Ulka. “For example, a road project is not especially climate friendly, but you can make it more so by creating a bike lane or protecting/adding roadside trees. This helps identify the exact funds being allocated for climate actions and where the opportunities are, and it becomes a way of mainstreaming climate concerns into any scheme.”

Rethinking health and education budgets

Many like Kathyayini demand higher allocations for public health this year, given how COVID exposed the inadequacies of the system. For example, BBMP still does not have one PHC (Primary Health Centre) per ward, and its hospitals are not functioning properly due to staff shortage.

Prasanna Saligram, public health researcher and member of the Jana Swasthya Abhiyana Karnataka, says that the repeated low allocations for health indicate a governance issue. “BBMP is in charge of less than 10% of the healthcare infrastructure in the city” says Prasanna. Major hospitals like Victoria and Bowring are under the state government.

“During COVID, for the first time, BBMP took leadership for health and tried to integrate all facilities including private ones, which is a positive step” says Saligram. “Such leadership and regulation of the private sector should continue, which requires budget to hire more staff. Otherwise, given the weak governmental health architecture in urban areas, citizens are left to the mercy of expensive private hospitals”.

Last year’s budget for public health and hospital infrastructure would mean allocation of approximately Rs 270 per person. Whereas, Prasanna says, the ideal investment for healthcare per capita is Rs 2,500-3,000 as per their calculations. But given that BBMP is cash-strapped and dependent on state government for funds, it continues tokenistic allocations which mostly services salaries.

Read more: BBMP budget: Is 336 cr enough to manage Covid, fix a broken healthcare system?

“There should be greater devolution of funds from the state government to BBMP, and BBMP should be able to decide where to spend in terms of health, depending on the needs of the people here,” Prasanna says. He gives the example of local bodies in Kerala which get untied funds from the state government, and have run programmes like dialysis centres depending on local needs.

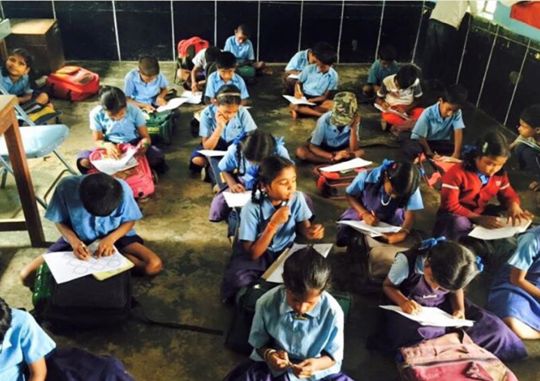

In the case of public education too, BBMP has been taking a narrow view by spending small amounts on the few institutions it directly runs. Dr V P Niranjanaradhya, Programme Head, Universalisation of Equitable Quality Education at the NLSIU (National Law School of India University), says this violates the RTE (Right to Education) Act. “As per Section 9 of the RTE Act, the local self-government has responsibility for all educational institutions in its jurisdiction, not just BBMP schools,” says Dr Niranjandaradhya.

He lists out key responsibilities of BBMP as per the Act, for which budget should be allocated:

- Mapping all schools (including private ones) within BBMP limits, and maintaining the records of all children up to the age of 14.

- Ensuring that all children in the city, especially migrants and other marginalised sections, are enrolled in school

- Providing core infrastructure facilities in schools as per RTE norms. Currently, only 23% schools in Karnataka have the core facilities mandated by RTE Act.

- Ensuring equitable, quality education to all children, especially for those from marginalised groups

- Ensuring that no child drops out of school before completing at least eight years of elementary education

Additionally, budget should be allocated to bring back children who had dropped out since COVID, and to bridge the learning gap. “Human resource allocation is needed for intensive door-to-door campaigns to identify children who were enrolled in schools as on 2019-20 and to bring them back,” says Dr Niranjandaradhya. “Children should also be assessed at the school level, and bridge courses should be conducted depending on their level of learning deprivation”.

Issues of workers, marginalised groups

With COVID lockdowns, Bengaluru has seen widespread job losses as well as protests by informal and contract workers. Last year’s BBMP ‘social welfare’ budget of Rs 319 cr (around 3% of the total budget) was mainly to develop basic infrastructure in SC/ST areas, and for welfare programmes for individuals from disadvantaged groups.

While pourakarmikas could apply for these schemes, Maitreyi Krishnan of AICCTU (All India Central Council of Trade Unions) says that BBMP should have a structured policy to ensure benefits to all pourakarmikas so that it doesn’t become a lottery. (Currently pourakarmikas need to apply for the scheme, and only get benefits if their application is accepted.) “They have to be entitled to housing/quarters and education for their children, as part of their service conditions,” says Maitreyi. “Besides, wages of contract pourakarmikas should be brought on par with permanent workers who do the same work. The budget has to account for this.”

A large section of other D Group workers in BBMP are also under the contractual system and should be shifted out of it, Maitreyi says. The majority of them are from Dalit/backward communities, and many have been working with BBMP for decades. “Besides, the payment for BBMP’s honorarium workers have to be increased, and also the garbage vehicle drivers and helpers have to be brought under the direct payment system”.

Maitreyi and Kathyayini also talk about the need to provide adequate housing to migrant workers. “As per a recent government order, workers’ colonies should be set up for temporary migrants in every ward,” says Kathyayini. “BBMP has to get funds from the Building and Other Construction Workers Welfare Board for this.”

Kathyayini says that BBMP should also set up sufficient anganwadi-cum-daycare centres, as per Supreme Court directives, to tackle malnutrition and benefit working mothers.

Does the budget-making process itself make sense?

“In the absence of an elected BBMP Council and Standing Committees for making decisions, the budget exercise is not credible,” argues Ashwin. “Also when BBMP asks for citizens’ inputs, it’s like a shot in the dark, and they may or may not use the inputs. BBMP could at least try to mimic the usual budget-making exercise – perhaps create a standing committee of citizens who will then collect information at the local level and get citizens’ inputs”.

Besides, the budget usually allocates Rs 2-3 crore for each ward. Areas Sabhas in each ward are supposed to create plans for this budget, and these plans are then collated and decided on by the ward committee. But Bengaluru does not yet have Area Sabhas, and the ward committees are not functioning formally in the absence of councillors.

Read more: Ward committee meetings lack proper rules, representation and legal framework

Rajendra Prabhakar who heads the community NGO Marga, says no bottom-up planning is happening in the absence of Area Sabhas. “Also, marginalised people are not participating in ward committees, and are not recognised, so slums are not represented anywhere in the ladder of governance,” says Rajendra.

Anjali Saini, a member of the citizen collective Whitefield Rising, says there is zero transparency on budget spending even for ward-level works. “BBMP should have a specific format by which a citizen can raise a request for ward-level spending (eg. replacing a broken footpath slab using road maintenance funds given in the budget), and a clear workflow of who should respond to the request at the ward level within a specified time,” says Anjali.