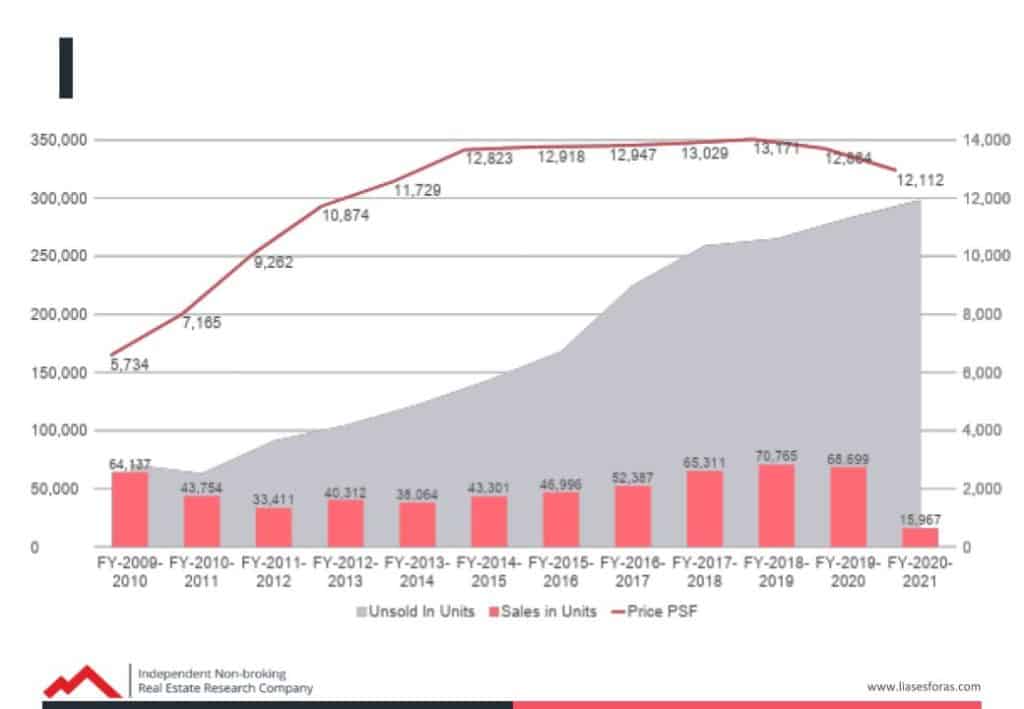

Every year, property consultants produce reports that highlight the many unsold flats in Mumbai. The inventory is almost at 3 lakhs in 2020, according to a non-brokering real-estate research firm Liases Foras. The number prompts an inevitable discussion about the lakhs of vacant homes in plush, gated enclaves while at least half of Mumbai’s 1.9 million people live in decrepit and squalid conditions.

The average per sq ft price for homes in the city has risen from Rs 5,734 in 2009-10 to Rs 12,112 in 2019-20. The number of homes sold haven’t caught up.

Although the prices fell in 2020-21 due to COVID-19-induced market uncertainty, the growth in the number of unsold homes in Mumbai is significant.

In this two-part series we will try to explain why, despite the many unsold flats, prices don’t fall to make housing affordable in Mumbai.

Rush to build luxury apartments

In 2005, DLF Ltd, India’s largest property developer, bought a 17-acre plot in Lower Parel, Mumbai, for Rs 702 crore. Eight years later, DLF sold the land parcel to Mumbai-based Lodha Group for Rs 2,727 crore—almost four times its initial investment. The deal was the talk of the town. It hit headlines and triggered speculative prices across Lower Parel for months to come. The Lodha Group, that prides itself on providing the “finest lifestyle” to its patrons, began constructing a residential project called “The Park” on the plot.

In late 2019-early 2020, people who could afford Rs 4+ crore for a 2BHK apartment began to move into The Park. But its six luxury towers and 2,371 units have only witnessed 506 sale transactions worth Rs 2,099.89 crore so far, according to Zapkey, an online platform which collects registration data from revenue authorities publicly available under Section 57 of the (Indian) Registrations Act, 1908. 1,865 apartments are reportedly unsold.

The Lodha Group took a loan of Rs 1,500 crore in 2013 to finance the Lower Parel project, and invited buyers to invest while the buildings were under construction. Now the company’s debt has swelled to ₹19,000 crore. Lodha’s creditworthiness has also taken a hit because of concerns around its financial health.

Like Lodha, many developers in Mumbai have raised money from the market to build premium and luxury apartments. They’ve aggressively pushed to build luxurious homes for high-income professionals but the demand has been fizzling off. As a result, developers have accumulated 2,98,529 units as unsold inventory in 2020, according to data shared by Liases Foras with Citizen Matters.

But Mumbai’s real-estate market defies the microeconomic demand-supply curve to remain stubbornly unaffordable. The story is not new, but is quite bewildering.

Relaxing restrictions

After liberalisation in 1991, foreign capital chased major cities in India, especially Mumbai, the country’s financial centre. Million-plus US $ transactions for fashionable apartments in Malabar Hill and similar areas often said to involve NRIs were invested, wrote Jan Nijman in his 2000 paper, Mumbai’s Real Estate Market in 1990s: De-regulation, Global Money and Casino Capital.

A deregulation had allowed NRIs to invest in India and this led to spiraling prices. For years to come, foreign capital flooded the limited land, resource and infrastructure supply in the peninsular city.

But 75% of transactions were “notational”, which means they existed only on paper and hadn’t been built, according to Nijman. “The real estate and developers business communities served themselves well—for a short while—by taking the market up,” Nijman added.

A not too dissimilar story repeated in the 2000s. In 2005, India allowed 100% Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in the township, housing, built-up infrastructure and construction-development project sector subject to certain terms and conditions (that were later relaxed).

Mumbai’s real estate market was the recipient of the highest FDI inflows. This, quite simply, changed the entire game of real estate funding.

“In the past, real estate companies or developers would put their own money into projects,” Sandip Kumar, Lead Consultant – Research & Advisory Services of Liases Foras, a non-brokering real-estate research firm, says. “If they borrowed money for construction, they would complete the project, sell it, and then move to another project.” But once FDI came in, developers got easy access to foreign capital. They stopped investing in their projects and started relying on private equity funding.

“As developers were no longer putting their own money, they were not responsible for it,” Kumar says. Nor was there a regulatory framework to hold them accountable. As a result, “speculations began, increasing the real estate prices in the market.”

| Time Period | Amount of FDI equity inflows (in India) | Amount of FDI equity inflows (in Mumbai) | Percentage |

| 2000 – 2010 | $10.27B | $3.92B | 38 |

| 2011 – 2016 | $14.28B | $3.24B | 22.6 |

The increased access of funds for builders propelled a price rise across the spectrum: from materials, cost of construction, labour to even taxation, Kumar says. Eventually, the builders acquired ill-repute for their financial indiscipline and lack of professionalism. “Fund managers would chase developers and developers would simply not entertain them,” Kumar adds. Many developers defaulted and in absence of a robust regulatory framework, they quietly slipped away.

Turning point for real estate sector

The increase in capital inflows changed the housing landscape from independent developments to large-scale real-estate projects. Money raised for one project financed the other and the focus remained luxury housing. Between 2006 and 2011, according to data by Liases Foras, only 9% flats that cost up to Rs 25 lakh were constructed in Mumbai, lowering an already dismal 21% in 2006. Simultaneously, flats that cost Rs 2 crore increased from 9% to 22%.

Prices rapidly rose after 2006 but the period from 2009-2012 was considered the boom period. This is also the time when supply further shrunk in Mumbai and a lot of affordable real-estate development began on Mumbai’s periphery in areas like Dombivli, Panvel and Navi Mumbai. Buyers who could afford flats in Mumbai or its many extended suburbs made meaty profits (see table below). Developers, too, easily pocketed double digit returns.

This surge in the market continued till 2014, after which prices began to fall, but only slightly. Land was still in short supply.

| Area | Annual Return (2010-13) | Annual Return (Jan 2014- June 16) |

| Mumbai (central) | 9% | 5% |

| South Mumbai | 9% | 5% |

| Suburb | 12% | 7% |

| Periphery | 15% | 6% |

Builder-politician nexus

Mumbai’s real estate is also fraught with stories of land acquired through unscrupulous means or siphoned from slum redevelopment or affordable housing. Many builders and politicians are implicated in a series of alleged scams.

In 2011, Times of India reported that a tripartite agreement was signed by the owners of a parcel of land in Powai (Niranjan Hiranandani, the Managing Director, of Hiranandani Group was their power of attorney), the state government, and Mumbai Metropolitan Regional Development Corporation (MMRDA) to develop a low-income housing township.

But MMRDA accused Hiranandani of “amalgamating smaller flats meant for public housing” and selling it as a “large unit to high-end clients”. The state government arbitrator absolved Hiranandani of fraud but later, a special Anti-corruption Bureau court pulled up the investigators for favouring Hiranandani and not even producing an investigation report.

If not land, builders are accused of selling ready flats meant for slum dwellers at market prices, or raising investments under false pretexts. “Politicians also influence land use to restrict supply of land for real estate development,” a senior sales manager at a real estate firm says on the condition of anonymity.

“There’s no real estate development in Mumbai without the politician’s blessing,” the senior sales manager says. Politicians are known to invest their illegal gains in real estate and influence what gets developed where, he adds.

Artificial price hike

Real estate development has also transformed many small-time developers into billionaires. They bought or inherited relatively cheap parcels of land decades ago and can now afford to hold on to unsold inventories without going bankrupt. This is one of the key reasons why prices don’t fall.

The artificial price hike due to financialisation, speculation and politicians’ interference has also steadily reduced the number of property launches in Mumbai.

If there were close to 1200 new property launches in 2008-09, they’ve fallen to less than 900 in 2016, according to data by Propequity, published by a Magicbricks and KPMG report.

In this scenario, those who can afford to buy a home in Mumbai are mostly those who already own one.