Rains pounded Chennai in the first week of November, reminding people of the horrors of the 2015 floods. But this time, the residents of Seethammal Colony were fast asleep, oblivious to the downpour. “When we woke up the next morning, we did not believe that it had rained the previous night,” says A Sridharan, the vice-president of the Residents’ Welfare Association of the colony, adding that the area used to be one of the hotspots of floods in Chennai until last year. However, this year, the newly laid stormwater drains (SWDs) were doing the job of keeping the roads free from inundation.

But this, unfortunately, is not true of all parts of the city. Some areas are still struggling with floods in Chennai, thanks to lack of proper flood mitigation infrastructure. To bridge the lack of working SWDs, the Greater Chennai Corporation (GCC) has been bringing pumps to remove water from the inundated areas in Chennai.

We look at flooding trends and the presence and absence of natural or/and man-made flood infrastructure in North, South and Central Chennai, and why some areas felt the hit more than others when it rained.

Read more: Chennai races against time to finish storm water drain work, but concerns persist

Changing land use and history of Chennai floods

Sudhir Kumar, an architect with Peoples Architecture Commonweal, a Chennai-based firm of architect-builders describes a time when Chennai had agricultural lands.

Back in 1973, almost 70% of the Chennai Metropolitan Area (CMA) had agricultural lands, before the Chennai Metropolitan Development Authority (CMDA) came up with its first Master Plan in 1975.

“In 2006, before CMDA came up with the Second Master Plan, CMA had only 12% of agricultural land,” notes Sudhir. “The total area under CMA had not changed up to 2019.” In other words, agricultural lands had been converted into industries and residential and commercial spaces.

According to a study, CMA’s farmlands decreased from 40,991 hectares in 1991 to 22,130 hectares in 2004.

“Most of the growth in Chennai has been on agricultural land, mainly paddy fields. They tend to be lower than traditional habitation because the fields are meant to hold water. Converting paddy fields into residential plots without referring to their historical use could have led to floods in Chennai,” says Sudhir.

Water flow channels have also been affected since the late 90s, due to the construction of elevated highways that cut through drainage basins, especially in the outskirts of Chennai. “Highways that connect Outer Ring Roads, perpendicularly cut through drainage channels and basins, thus hampering the water outflow towards the sea,” says Sudhir.

Floods in South Chennai explained

“After Adyar, the next major river is Palar. There was no way for the water to flow and drain toward the southeast direction. This might have led to the formation of the Pallikaranai marshland,” says Sudhir. Pallikaranai wetland remains a key component in natural flood mitigation in South Chennai. However, in the last three decades, 90% of the wetland has been built on. Many low-lying areas near the wetland were inundated in the 2021 floods.

For example, Thoraipakkam is a locality adjacent to the Pallikaranai wetland, along the IT Corridor. “It is not any different from previous years in Thoraipakkam this year. The majority of the areas are yet to get stormwater drains,” says Shyam Sundar, a resident of Thoraipakkam. “When it rains, roads suffer water stagnation.”

Apart from wetlands, lakes and other waterbodies also play a role in flood mitigation in South Chennai. But when they are not maintained properly, it can exacerbate the impact of floods in Chennai.

“There are 4000 plus lakes in Kanchipuram and Chengalpattu districts. But inflow and outflow channels are not maintained properly,” says Darwin Annadurai, founder and managing trustee of Eco Society India, a registered non-profit-environmental-citizen-group. “The outflow of the upstream lake is the inflow of the next downstream lake. In many cases, these channels are encroached upon, diverted or abruptly end in a no man’s land.”

“For instance, the outflow from Ottiyambakkam Lake abruptly ends near the DLF City campus. It should reach Pallikaranai marshland,” Darwin cites as an example. “When inflow and outflow channels are not proper, then the excess water from the lakes will spill over to the land areas, which may cause flooding.”

Narrowing of inflow and outflow channels also causes similar flooding risks. “30 to 40 feet would be the width of these channels. But with urbanisation happening, the channels shrink to a width of 3 to 4 feet,” says Darwin. “How will the water from a huge lake flow within this small width?”

Areas around Besant Nagar and Thiruvanmiyur have sandy soil which can drain water naturally and recharge the water table. Flood mitigation measures here should look at integrating recharge wells apart from introducing SWDs in areas with sandy soil.

Why Central Chennai floods

The area between the rivers of Cooum and Adyar falls roughly as the wards in the Central zones of Chennai. “The flooding situation is relatively better here because of an organised stormwater drain system. But we lost a lot of water bodies in this region too, like the Mandaveli Lake,” says L. Elango, Professor and Head of the Department of Geology at Anna University. “The lake started near South Usman Road and led up to Tank Bund Road.”

The civic body has constructed, rebuilt and repaired the SWDs in Central Chennai apart from some parts of North and South Chennai to mitigate floods. Seethammal Colony and Bazullah Road are among the areas of Chennai which have seen extensive work on SWD systems.

“SWDs in T Nagar are a good example of necessary infrastructure to prevent flooding. The drains get wider as they come closer to a disposal point, to carry all the rainfall from the catchments of different locations. There has been no inundation in Vijaya Raghava Road, Pondy Bazaar, Dr Nair Road and GN Chetty Road in T Nagar so far this year,” says Dayanand Krishnan, a Geographic Information System (GIS) expert.

“But we do not see the same idea getting replicated in Ashok Pillar, near Kasi Theatre among other places. All the SWDs must have an outfall at the MGR Canal, which runs parallel to the road, but the civic body has not done it. Moreover, the area near Kasi Theatre has around 1.4 metres of elevation. Naturally, it will flood the locality,” says Dayanand.

In NTR Street, Rangarajapuram, SWDs are present but there are design and urban flaws which make the drains defunct, says Radhakrishnan, a resident of Rangarajapuram. “The civic body had to pump water out of NTR Street in Rangarajapuram on November 11, after heavy precipitation,” says Radhakrishnan.

North Chennai’s flood woes

Some localities in North Chennai like Thiruvotriyur and Vyasarpadi have been battling floods this year. SWDs are yet to be laid completely in the northern and southern parts of Chennai.

“North Chennai has been the industrial hub since colonial times. Moreover, the population density in this part is greater than in South Chennai,” says Sudhir.

Soil also plays a part in flood mitigation, by recharging groundwater and run-off water. “North Chennai has fine-grained sediments like silt and clay,” says Elango. Silt and clay retain water more than sandy soil, which makes North Chennai susceptible to flooding, and the risk is heightened with a large population.

“North Chennai has natural surface water drains like Buckingham Canal and Otteri Nullah, which takes the bulk of the water to the Cooum and Kosasthalaiyar rivers,” says Elango. “Because of that, we can help reduce inundation except for some surface depressions, like the south of Ennore, which was previously marshlands. From there, we can remove water only by pumping,” says Elango.

Read more: Saving Otteri Nullah: Desilting alone may not hold the key

Western parts of Chennai face inundation

Areas like Iyyapanthangal and Moulivakkam saw people being ferried on boats to go from one spot to another due to inundation of around three feet.

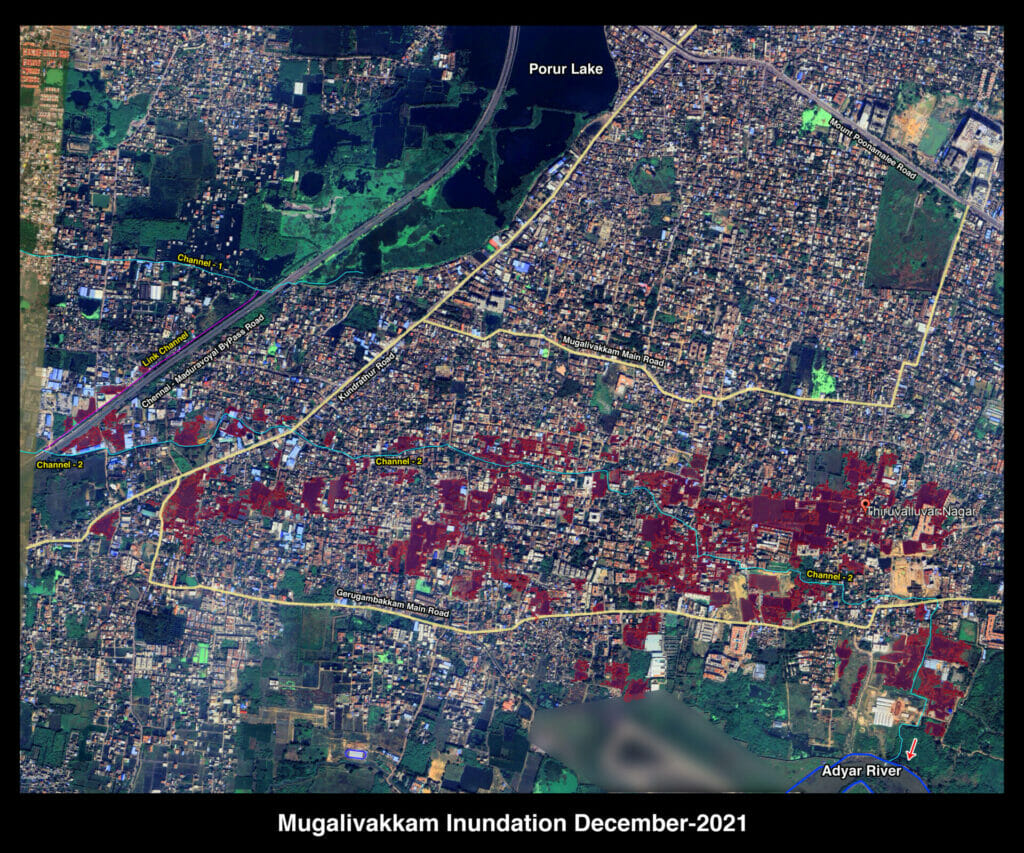

Mugalivakkam, an area close to Moulivakkam is also experiencing inundation. The former is part of Ward 156 of GCC, which has faced recent flooding due to the overflowing of the Porur lake.

An SWD channel (Channel 2) starts from Chemberambakkam Lake and ends at Adyar River via the Chennai-Maduravoyal Bypass Road. “The channel passes through dense residential areas, sandwiched between Mugalivakkam Main Road and Gerugambakkam Main Road,” says Dayanand, who has studied the inundation in Mugalivakkam that happened in 2021.

“The channel does not take floodplains into account. Therefore, the channel has breached, flooding the low-lying areas. Wider channels with retaining walls must be built to receive excess water from upstream areas,” says Dayanand.

Bare earth can be a barrier against floods in Chennai

“Water-holding reservoirs like the wetlands in Chennai are not the only landscapes that help in draining water. We need to also look at the abilities of bare earth and covered earth [like bitumen roads] [in flood mitigation],” says Sudhir.

Bare earth absorbs water, while covered earth usually generates run-off unless the covering is made of porous materials. Around the globe, around 3.2 trillion tons of water has been absorbed by the soil, underground aquifers and freshwater bodies, from 2002 to 2014, as per a NASA report.

“Stormwater drains are constructed in densely populated areas, increasing the amount of water entering into canals and rivers. This undermines the ability of the land to hold and absorb water,” says Sudhir.

“The priority of SWDs aligns with the priority of construction activities [in Chennai],” he opines.

Engineering solutions to solve local flooding problems

Urban forests can reduce flood impact, says Darwin. “There is run-off water even when there are 0.5 centimetres of rainfall. But if there is a forest cover and a rainfall of, say, 5 centimetres of rainfall per hour, there will not be any run-off,” he says, adding that the burden on SWDs will reduce. The green cover will absorb the water and recharge the water table.

The buffer zones or the banks of waterbodies can be used to plant trees. “This will increase the water absorption rate of the soil,” says Darwin.

“Parks also play a role in holding flood water, similar to retention ponds. Traditionally, they were constructed at a level lower than the habitation level. Now, the modernisation of parks with elevated levels robs the purpose,” says Elango.

Another solution would be to bring a line of earth covered with pebbles near the sidewalks for natural rainwater absorption by the soil, along the roads in Chennai, says Elango. “This will ease SWD’s burden to carry all the run-off water.”

With climate change tightening its grip on cities across the world, it is essential to understand the trends in flooding in different parts of Chennai to evolve strategies for prevention and mitigation. Different parts of the city have different topographic makeups, different soil, and other natural flood-resilient infrastructure, apart from the knowledge possessed by local residents to battle floods. It is time to customise flood mitigation measures across the city instead of pursuing a one-size-fits-all approach across Chennai.