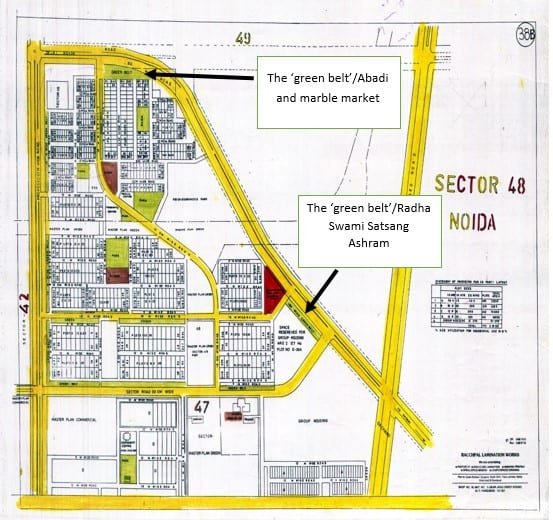

On June 18, 2019, the New Okhla Industrial Development Authority (NOIDA) sent a team of personnel and machinery to reclaim a 5-acre plot along the Dadri-Surajpur-Chalera (DSC) road in Sector 48 (Map 1 below). The plot, a part of the Barola village agricultural land, was acquired for developing NOIDA in 1976. The Authority claims that most landowners took compensation for the loss of their land. Since the official master plan of the city (NOIDA Master Plan 2031) shows the plot as a ‘green belt’, the marble market that sprouted there in early 2000s, alongside some old and new pucca residences, face demolition.

But things are a bit more complicated than this. The immediate spur for eviction was a writ that a few middle-class residents of Sector 48 had filed at the National Green Tribunal Principal Bench (NGT) in 2017. They prayed to the bench that the “green belt area, as given in sector lay out map during allotment by NOIDA” be restored. On March 13, 2019, the NGT ordered that the entire area earmarked as a green belt be cleared “within a period of two weeks”.

As demolition began on June 18, scores of villagers and political activists converged on the plot in protest. They insisted that several families were living in their animal/farm yards (gher) on the plot at the time of the notification. Hence, NOIDA itself had “decided” to return the plot to the inhabitants in its 191st board meeting in 2011, acknowledging the plot to be a part of the village settlement (abadi). The point that many landowners in the plot had refused taking compensation, preferring litigation, was also emphasized.

Therefore, the villagers saw the writ, the NGT order, and the demolition drive as an evidence that the Authority and the sector residents were colluding to uproot the villagers on the pretext of restoring green belts. They apparently saw themselves as victims of oppression.

Facing protest, the Authority personnel retreated on the day. But the villagers believed that the demolition would resume soon. From June 19th morning, about hundred Barola residents commenced an indefinite dharna on the market site, under the banner of the Bhartiya Kisan Union (Bhanu), an influential farmers’ organization in Western Uttar Pradesh. The dharna continued until June 30, when the Authority agreed to halt the eviction drive for a fortnight.

We, the researchers, attended the dharna for five days (i.e. June 20th to June 24th, 2019) and also met with local residents, village notables (Pradhan), and a range of political activists from across surrounding villages participating in it. And from these conversations, emerged narratives that underlined the claims of the ‘rural’ on urban spaces in an almost de-agrarianized milieu of NOIDA.

The most common and vivid of these narratives presented the urban-rural as a space of peeda (pain) and peedit (the sufferer).

Tales of peeda

Both participants at the dharna and common villagers used the Hindi adjective peedit in their speeches and in conversations with us. They used it in four overlapping contexts.

In the immediate, the term referred to the families that risked eviction from their homes and rented-out shops if and when the Authority cleared the plot. Such peedit families were urged to stand up for their homes and villages by attending the protest for as long as it continued. Moreover, such families identified themselves as the peedit.

30-year-old S Chauhan, one self-identified peedit, took me to his residence that appeared to have been built three or four decades ago, behind which stood his construction material shop. He believed the eviction would ruin his family and its economic well-being.

The real social and political cause of suffering, however, lay in claims that villages in NOIDA had been continually oppressed by the Authority, the wider State and the ‘sector-wale’ since 1976. Such claims refer to land expropriation by the state and compensation paid.

“The government wrested our lands at Rs 2 or 3 per gaj (9 square feet) during the Emergency, which they are selling for tens of thousands of rupees now in these sectors,” one villager said. “They claimed then that our land was going for industries in which we were promised jobs, but they eventually sold land to builders; except for a few who got jobs, we remain jobless.”

“We were to get 5% (of the total land acquired) leased back to us as developed plots in sectors, as the Allahabad High Court ordered (2011), but most of us have not got it as yet,” his friend said. “They have sold all land as sectors and to builders, now NOIDA has no land left to lease us back!”

Almost all of the 44 villagers within and outside of Barola that we talked did admit to having received the original as well as the revised monetary compensations. But they grieved as commonly at the paltriness of the monetary compensations in comparison to the going real-estate market prices. The non-fulfillment of non-monetary parts of compensation—jobs, and developed plots—was particularly seen as a betrayal by the Authority.

The third dimension of their peeda rested on the claims that villagers were selectively punished for land-use violations. “Temples and ashrams (pointing to Radha Swami Satsang Ashram on the DSC road; see map 1) stand in green belts in these sectors, but the Authority is blind to them,” say the protesters.

The villagers demand that the Authority should tell them “how many kothis (or mansions) of NOIDA officials in these sectors follow the laws; when sector residents violate, the Authority takes money to regularize them, but if we construct even a room in the village, it comes to demolish our homes.” Outsiders (bahar ke log) in the sectors and in the jhuggis allegedly get away with violations, while the mool-nivasi (original inhabitants) of this region, are hounded out for earning their living.

The beleaguered ‘rural’ in the urban

Summarizing social change for all the notified 81 villages in NOIDA is difficult. Land has been acquired in phases and villages are locationally different from one another. But if agricultural lands from the villages have been acquired to provide settlements for middle class sectors since the 1980s, the villages themselves have also seen a demographic turmoil in the last two decades.

Barola village claims a population of more than 100,000 residents today, whereas only 5,000-10,000 residents lived here in the early 2000s. Similarly, Hoshiyarpur village in Sector 51 claims a population of more than a lakh now. A majority of the new residents are emigrants of different economic strata and cultural backgrounds. Rentals from emigrant tenants form the main source of livelihood for most villagers.

So, urban villagers find their everyday social experiences entangled with those of the “outsiders.” From sharing tobacco pipes (hookah), collecting rent and visiting the gated sector parks, to fighting the Authority for compensation and land use violations — these villagers are continually engaged with two different sets of outsiders.

The middle-class “sector-waale” are in the first set. Tenants—some living in pucca houses and others, in rented out shanties inside and on the edges of the village—form the second set.

This is what creates the fourth context of their peeda. Villagers often grieve that their villages have “become slums”. They rue that their houses and drinking water taps are flooded with sewage following a single spell of heavy rain while garbage remains unattended on the streets. Sector schools, on the other hand, are allegedly reluctant to admit their children, and sector parks don’t want to let them in, because they are seen as “trouble-makers” and “uncivilized”.

Finally, villagers said that they were losing control of village affairs due to the demographic changes created by influx of people. Since slums were seen as inferior spaces, empathy for jhuggis wasn’t often a part of the idiom of peeda.

[This article has been co-authored by Nilotpal Kumar, Assistant Professor at Azim Premji University, Bengaluru and Ritanjan Das, a Senior Lecturer at the University of Portsmouth, UK. All pics were taken by the authors.]